American Ballet Theatre arrives this weekend with La Bayadère, a full length Russian classical ballet regularly presented in repertoires around the world, but rarely seen in full in the U.S.

So, what is La Bayadère and why is it so rarely performed in the U.S.?

Choreographed by Marius Petipa (1818-1910) and premiered in 1877 by the Tsar’s Imperial Ballet, La Bayadère was midway among Petipa’s 150 ballets, reflected the Victorian era fascination with faraway places with strange sounding names, and presented a sumptuous spectacle consistent with the ballet-loving Tsar’s status as the richest man in the world.

Set in India, La Bayadère’s tragic love triangle bears strong resemblance with the better-known opera/musical theatre Aida where a triumphant warrior is his sovereign’s choice to marry the ruler’s daughter, but the warrior is in love with another, here a sacred temple dancer (the “bayadère” of the title). With the original four acts now three, in what is now a busy Act I, there’s betrayal by the temple’s head priest who has unpriestly eyes for the temple dancer Nikiya, efforts at bribery by the Rajah’s daughter Gamzatti, and a flower basket with a poisonous snake. In what is now Act II, known as the Kingdom of the Shades, the soldier Solor’s opium induced vision leads to the ballet’s signature mystical procession with 24 ballerinas descending in unison down zig zagged ramps, followed by an extended pas de deux with the lovers. The third act opens at the wedding of Solor and Gamzatti, but devolves into vengeance and reunion beyond the grave.

A staple in the Russian repertoire, the ballet was unknown in the West for nearly a century. That changed when the slight thawing in the Cold War allowed cultural exchanges between the Soviet Union and the West. La Bayadère was included in a 1961 Paris tour by the Kirov Ballet and Western balletomane appetites were whetted for more. Russian defectors responded with productions based on their memories of the ballet. In 1963, Rudolf Nureyev set the ballet’s most famous act, the Kingdom of the Shades for Britain’s Royal Ballet, followed by multiple full-length La Bayadère productions in Europe and beyond.

Crossing the Atlantic was another matter. La Bayadère did not make it to the U.S. until 1974, when another Russian defector, Natalia Makarova, staged the Kingdom of the Shades for American Ballet Theatre. The critical and popular response was strong, especially for the performance of the corps de ballets, but it took six more years for ABT to mount the full ballet with Makarova again at the helm. Despite the production being televised as part of the PBS series Live from Lincoln Center, the ballet’s challenges are daunting and until recently, rarely part of U.S. companies’ repertoire. In a hopeful sign, Boston Ballet and Richmond Ballet are among those with productions ofLa Bayadère Act II, stepping up to field a corps de ballets able to meet the legendary challenges of the Shades.

ABT ballet mistress Susan Jones was the third of the 24 Shades descending the ramp when Makarova staged the Kingdom of the Shades in 1974. Jones now is the ballet mistress for La Bayadère’s Shades among her other duties. That she knows her stuff is underscored by Makarova designating Jones to stage not only the Shades, but also the entire ballet in countries all over the world.

Interviewed by phone, Jones thought the recent week of La Bayadère performances in New York demonstrated ABT’s corps is actually in a better place than when the ballet was first staged in 1974.

“At that time, except for several dancers from the School of American Ballet, we had come from at least 20 different ballet schools with different training that produced slight differences in important details such as exactly where an arm should be or a head position and the like.” Jones noted that while small, those differences required Makarova and the then ballet masters to devote considerable attention to adjusting those details and a larger sense that Jones described as “instilling in the 24 dancers not so much a sense of moving as one, but breathing as one, being married to each other.”

“While all those elements are still an important part of my work, today we have ABT’s affiliated Jacqueline Kennedy Onassis ballet school, the studio company and the apprentice program,” Jones said, “so the dancers join the corps with several years of training in those important details that are what ABT wants to instill in its dancers”. Jones described one adjustment the studio company made after realizing solo works were being emphasized, “now dancing in a group is receiving emphasis,” Jones noted with a chuckle. Jones still devotes early rehearsals of the Shades to breathing. “Breathing from the solar plexus is the key to the unity in the Shades even if a different conductor has a slightly faster or slower tempo in a performance.”

Countries with state sponsored ballet companies generally draw corps dancers from students trained by the affiliated ballet school in the specific style of the company. Entry to the school is difficult with students carefully selected with an eye to the demands of a particular style and look as well as the need for a large corps de ballets. As they progress through the school, students gain an understanding of whether their career will be in the corps de ballets, as a soloist or a principal. In these ballet companies, being in the corps is regarded in a manner similar to being in an orchestra or an opera chorus where the ability to combine with others to create a unified effect is valued and regarded as a respectable career achievement.

By contrast in the U.S., many companies performing classical repertoire hire dancers who come from schools teaching different techniques even if they later trained with the company-affiliated school for a year or so before joining the company. Add to that a prevalent attitude toward ballet in America that the corps de ballet is a starter position, a sort of mailroom from where one should expect to move on and rise through the ranks to become a prima ballerina. Also, young dancers who were the stars in their ballet school tend to be used to concentrating on solos rather than learning to dance with others as the corps de ballet is required to do. Company ballet masters/mistresses tasked with rehearsing the corps must contend with dancers trained in a variety of styles and often with little performance experience sharing a stage or moderating personal interpretation to being part of a group. In addition to figuring out how to reorient and retrain dancers to the ballet company’s particular style for corps work, ballet masters/mistresses also often confront the perception that being part of the corps de ballet lacks value or respect.

Dance writers delight in describing the entrance of the Shades, an arabesque sequence that first one dancer performs, then repeated with a second dancer, then with a third and so on. While the steps are somewhat standardized, YouTube clips and performance videos reflect differences among the Russian, the Nureyev, the Makarova and other versions. Some have alternating Shades arabesque on different legs, some have all dancers’ arabesque on the same leg, and still others have dancers’ arabesque on the same leg while on the ramp, but then alternate dancers take an extra step and everyone onstage is on different legs. Some have dancers in a deeper plié, in other dancers have a higher arabesque position, others go for a deeper arch backward, and other slight differences. The number of Shades vary. Makarova’s version has 24. Nureyev’s generally 32. Petipa originally set 32, but for a gala he once had 48 Shades. Variations on the number of Shades and specific steps are consistent with Petipa revising his choreography over the years and others who succeeded him making their own revisions to the ballet which included tightening the original four act spectacle to a still lengthy three acts. Whatever the number of Shades or particular steps, the challenge is for each corps member to look like a mirror image. When everything clicks, the effect is mesmerizing and can earn applause for the corps that exceeds that for the principals.

Marius Petipa’s final revival of La Bayadère, with the stage of the Mariinsky Theatre shown in the scene The Kingdom of the Shades. In the center is Mathilde Kschessinskaya as Nikiya, Pavel Gerdt as Solor and the Corps de ballet. The three soloist shades are seen kneeling to the left: Varvara Rhykhliakova, Agrippina Vaganova and Anna Pavlova performed the shade’s variations. St. Petersburg, 1900.

So exactly who are the Shades and what are they doing in the ballet?

The act opens with Nikyia dead and Solor despondent but comforting himself with an opium pipe when he sees a vision of Nikyia that fades only to be replaced by the first Shade coming down that diagonal ramp.

Monica Mason, artistic director of Britain’s Royal Ballet describes the Shades “as wisps of smoke from the opium pipe.” Other frequent descriptions find the Shades are Nikyia replicated in Solor’s opium-induced hallucination. Jones has an additional perspective. “When those scarves that drape from their shoulders to their hands form a line, the Shades are making a connection from the afterlife that leads Nikiya back to Solor in the world of the living.” Jones explained. That observation also reflects another signature moment later in the act when Solor and Nikiya are holding separate ends of a long scarf and he partners her with only the scarf while she repeatedly turns in arabesque.

For ABT’s opening night here Misty Copeland dances the Raja’s daughter Gamzatti with Isabella Boyston as the temple dancer Nikiya and Jeffrey Cirio as the warrior Solor. Saturday Hee Seo is Nikiya, Gillian Murphy is Gamzatti and Cory Stearns is Solor. Sunday matinee the leads are Devon Teuscher, Christine Shevchenko, and Joo Won Ahn, respectively.

After these performances, La Bayadère goes into hibernation until 2020 when it returns with the Shades to celebrate La Bayadère’s 40th anniversary with ABT. Not bad for a ballet that started at ABT when it was nearly 100.

Music Center, Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, 135 N. Grand Ave., downtown; Fri.-Sat., July 13-14, 7:30 p.m., Sun., July 15, 2 p.m., Limited ticket availability as of press time $38-$60. https://www.musiccenter.org.

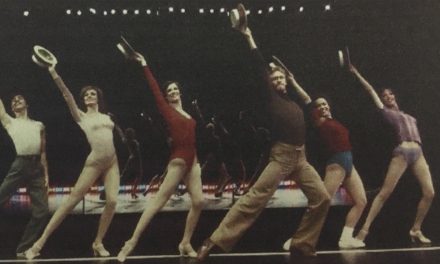

Feature Photo: Joseph Gorak in ABT’s La Bayadère – Photographer: Marty Sohl

More information on American Ballet Theatre, click here.