In this three-part series for LA Dance Chronicle, I am studying the various ways that bullying and gender interact, affecting leadership, individual success and failure, mental health, and representation in dance. If you are coming to this series fresh, you can read the introductory article here. The second piece looks at bullying and the gender gap in leadership. This final piece addresses gay, lesbian, gender fluid and queer representation in dance, both how dancers who don’t fit into the binary have been quashed and how the dance community is finally expanding and starting to include all voices and stories, both in and out of mainstream companies.

#BoysDanceToo began to trend after the hosts of Good Morning America bullied England’s Prince George for taking ballet and the dance community went wild. Our community fought back, with dancers posting photo after photo of gorgeous men flying through the air. Our dance royalty took to the airwaves with a follow up interview and gave a ballet class in Times Square. The power, grace and masculinity of dance was extolled and celebrated. It was beautiful but very specific. The photos and videos were of traditionally masculine dancers, heavily muscled, showing off incredible athleticism. There were the requisite “football players take dance” articles and endless anecdotes about the strength of ballet dancers. It started to concern me, all of this focus on hypermasculinity. It is undeniably beautiful and an important aspect of dance, but certainly not all of it, nor even the majority. ALL bodies dance, and as I started to look at bullying in dance, to hear story after story of the pain, repression and loss that so many dancers experience, I was drawn to join the exploration of gender beyond the male/female binary and whether dance, a deeply patriarchal institution, is adapting to today’s evolving gender and sexuality norms.

There are a lot of definitions regarding gender and sexuality. I want to thank The Radical Copyeditor for their guide, which I found indispensable. A reminder that the language of gender identity and gender expression is constantly evolving and it is on us all to remain open and flexible. The dancers that I interviewed identify as follows, so these are the terms that I will employ in this article.

Sexual orientation: Who one is (or is not) attracted to.

Gender orientation: One’s gender identity and expression of gender

Cis-gender: A person whose gender aligns with that assigned at birth

Transgender man: A person assigned female at birth who identifies as male.

Transgender woman: A person assigned male at birth who identifies as female.

Trans: Both an abbreviation for transgender and a more inclusive term for all whose genders differ from those assigned at birth.

Gay Man: A man (cis or not) who is sexually attracted to men.

Lesbian: A woman (cis or not) who is sexually attracted to women.

Non gender conforming: a person whose gender expression (by way of dress, mannerisms, roles, etc.) does not conform to stereotypical gender expectations for someone of their gender.

Non-binary, or gender non-binary: a person whose internal sense of self is not exclusively woman/female or man/male. Some non-binary people identify as both woman and man (e.g., bigender people), some identify as a different gender entirely (e.g., genderqueer people), and some do not identify with any gender (e.g., agender people).

Queer: another sexual orientation, neither straight nor gay. According the Radical Copyeditor, “Queer is a complex word with many different definitions, and in the context of trans communities, it must be recognized as a valid identity term.” It can also be used as an umbrella term to differentiate from cisgender and heterosexual.

For detailed definitions check out the Human Rights Coalition list of terminology and definitions. Finally, a reminder that identity and sexuality are very individual and each person will have their own identity, story and relationship to their own sexual and gender identity.

Before I jump in, some caveats. These are the particular stories and experiences of these people. In no way is this article reflective of the experience of all dancers. And, once again, I am not speaking to the particular situations that Black and Brown dancers experience in the realm of gender and sexuality in dance. The intersectionality of race, gender and sexuality is complicated, intensely important and warrants much more additional and specific research. Finally, this article focuses on Western Dance, specifically American ballet, contemporary and modern dancers and companies.

The first layer of my exploration of the acceptance of different genders and sexuality in dance started with the hyper masculine response to the bullying of Prince George. #BoysDanceToo and #BoysDance trended quickly and the photos on Instagram and Facebook were gorgeous but in general, hyper-masculine. I admit that I too posted photos of men flying through the air from my most recent piece, celebrating their athletic glory. But I also paused. The spectrum of those who dance is broad and includes so many bodies. Not everyone is highly muscled and stereotypically princely. There are numerous dancers who identify as male who present in a softer, less aggressive manner. How does this emphasis on hyper-masculinity affect dancers who do not fit into that lane? And would these same dancers come to the defense of others in the community who might not be as visible nor be perceived as such a valuable commodity.

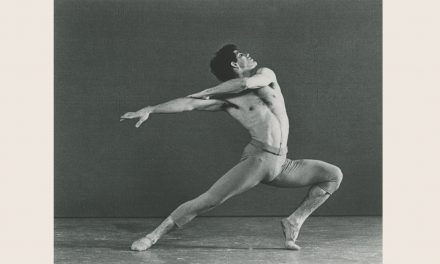

I spoke to two cis gay men and two trans men about their experiences in the dance world and how masculinity in all forms has affected their presentation, goals, sense of self and professional trajectory. Andrew Pearson is a Los Angeles based dancer, choreographer, dance educator and Artistic Director of Bodies In Play. Spencer Ramirez is a bi-coastal dancer and teacher who attended Juilliard and has gone on to dance with numerous concert choreographers including Mark Morris, Chase Brock, Body Traffic, as well as for countless commercial choreographers and as a Broadway hoofer. Sean Dorsey and Ashley R.T. Yergens are both out trans men forging successful careers in concert dance. Yergens, a Dance Magazine 25 to Watch in 2020 honoree, lives and works in New York. Dorsey, one of the pioneering trans artists in the country has a company in San Francisco. None has had a clear or easy journey, facing discrimination, bullying and disappointment along the way.

Sean Dorsey – 15th Anniversary – Photo by Lydia Daniller

When asked what gender expectations or norms they had struggled with, especially as young dancers. Ramirez said, “I do remember constantly being expected to fit into the classical ballet archetype of “Male and female”. As a man, I was meant to imitate that bravado, machismo figure constantly. The men are the frame and the women are the picture. Although I never really took issue with it, because I loved pretending to be this strong manly character, I do realize the boxes that it places young children in at such an early age. I’m glad to see that slowly in the dance community these days, young men and women are being allowed to explore outside of the classical archetype and find their individual voices, but there is still a long way for it to go. We find it in the professional (commercial) industry too though. When I first moved to LA, my agent told me I ‘needed to build muscle and act more masculine at auditions’ if I wanted to book any work.” Pearson had a similar experience in regard to body expectations in the more classical world. I was told that “I should be taller and/or more built and muscular. I’ve also had choreographers and teachers assume I’m not strong enough for certain lifts or be surprised when I can achieve them. However, this has been rare. I’ve avoided the more classical work and mostly worked with choreographers and companies that don’t take these kinds of norms into consideration or place them as a value.” Yergens spoke of the journey that he has taken in regard to gender and dance. “Prior to transitioning with HRT, I was quite literally told to move more ‘gently’ and ‘femininely.’ Now, I’m not ‘masculine’ enough. In a static image, I pass as a cis-gender man. However, when I move, I feel like I see two different bodies that perhaps have two different genders, and they’re struggling together to communicate movement. I think this is a result of not having balletic or contemporary training in this new body, and I’ve unfortunately received the message enough times that a dancing body should consist of this knowledge in order to be a ‘professional’.”

These artists articulated, with much more eloquence than I, a similar discomfort with the bullying episode of Prince George and the one-sided jump to defense of masculine dancers. Yergens had a viscerally emotional response, which I share in its entirety. “As a society, we bully cis boys for dancing because of homophobia and our unchecked ideas of appropriate femininity. I stand up for cis boys and cis men. I just wonder if they always stand up for me too. I wonder where the outcry was when I got made fun of for looking too much like a boy in my leotard in the second grade. I wonder where the rage was when I was 16 and forced to do the men’s choreography because I moved “too manly” yet the choreographer refused to acknowledge me as the man that I am because of transphobia. I wonder where the other voices were when my professor told me I was “such a hairy woman, and it would be unfortunate to partner with you” in front of 20 classmates. I wonder where safety was when I first started hormone replacement therapy, and the cis men laughed at me in the changing room, and the cis women yelled at me to get out of theirs …I wonder where the fury was when a prolific gay artistic director asked me if I “transitioned to be more palatable” to his tastes, as if my body’s sex exists to whet the appetites of cis men who would never actually partner and love me in the way that I deserve to be loved because I’m “not a real man.” I wonder if you can relate to the pain of having a choreographer purposely misgender you and ask you to move more like a man at the same time. I wonder if the gorgeous dancing cis men in their gorgeous directorial and creative positions will ever open up the field’s gates for trans men like me.”

Dorsey too had a multi-layered response. “I found the dance field’s overall response to the Prince George bullying incident fascinating – and overall disappointing. Yes of course we should rise up and speak out when young cis-gender boys are bullied simply for studying ballet. But that should have only been one element of a much larger, intersectional conversation. Unfortunately, it’s about as far as the media and the mainstream dance field went. Where was the outrage for the immense bullying and harm to trans girls and boys and non-binary kids who want to or are studying dance? Where was the outrage around white supremacy in the ballet field and modern dance field (and America in general)?” He continued, “And why did the entire conversation largely REINFORCE toxic masculinity ‘hey, men ballet dancers ARE strong, tough and they’re still REAL MEN!’ rather than tackling it ‘we reject homophobic and transphobic toxic notions of masculinity! Instead, we celebrate the glorious, full range of human expression available to all of us who love ballet – we are strong, we are fluid, we are expressive, we are tender, we are vulnerable, we are beautiful!’.”

Both Dorsey and Yergens shared numerous stories throughout their life journeys of bullying and isolation in the dance world. These experiences are absolutely elemental to their identity as dancers, trans men and artists. Dorsey recounts one of his first experiences as a very young choreographer. “That first piece of choreography I made at school was definitively queer – and like much of my work to follow, based on a text-based original soundscore with my own writing. It was a queer duet, and it was SUCH early work of mine, but I was floored when the local dance community all came up to talk to me afterward and said that they loved my movement vocabulary and my young choreographic voice; they said they couldn’t wait to see what I’d do in the future. I was elated! The next day, the Director of my school called me into her office. She sat me down and said “your piece last night made people feel very uncomfortable. “I remember that moment like it was yesterday (even though it was 22 years ago!). In that moment, all the experiences I’d had of the rigidly gendered dance world, costuming, hetero-normative expectations, everything came flooding back. And in that moment I also realized: I had found my calling. THIS is how I could affect change in the world; my deepest passion and desire is to be of service in the world – and I realize in that moment that I could shift people. And possibly culture.”

This idea and desire comes up over and over among these artists: This is how to be the change! The artist and the activist as one. It is incredibly brave to put one’s soul on display in that manner. To that end, sexuality and gender identity is integral to the work of all of these artists. Pearson explains his process. “I think the way I see the world as a dance maker and as an out gay man have definitely been affected [by his sexual orientation]. My gayness is intrinsically connected to the way I make work now. For years this was not the case, keeping my personal life separate from my performance/work life, but I found I couldn’t make dance authentically unless I confronted my sexuality. I now have an aversion to heteronormative approaches to dance making, or at least unconscious choice making that sway toward heteronormative.”

Trying to fit into a set idea of masculinity is difficult, especially when the definition itself is constantly evolving. Pearson said, “For the first – I think masculine energy is not gender specific but that in dance it personifies strength, bound flow, and more boisterous virtuosity. This has usually manifested in large jumps, multiple turns, showcasing power. But again, I don’t think any of this has to be gender specific.” He continued, “I’m over this argument. It’s dated, one-sided, and suggests an apology for men doing anything that may seem feminine. I don’t feel anything like a football player. I don’t identify with that game or with the people who play it. I don’t need people to know that football players take ballet to justify my love of the practice.” He also echoes Dorsey’s take on toxic masculinity. “I also certainly am not in dance in order to touch girls all day – which also feeds into today’s rape culture, suggesting that if a man is in a dance class he has the right to touch women.”

As I began to talk to dancers and health advocates working in the dance world, it became quite clear that one group of dancers is essentially invisible in much of Western dance, particularly ballet: Lesbians. I was actually quite thrown off my center! I am from San Francisco and was shocked that I could not think of a single lesbian working in classical ballet. Many of my male teachers were out gay men, but the only lesbian dancers that I could identify were part of a “radical feminist” (intentional use of quotes) dance company and school called SF Dance Brigade, directed by Krissy Keefer.I started to do some research and interviewed four amazing dancers about their experiences. Kathleen Maguire Gaines of Minding the Gap introduced me to Courtney Bold, a dance educator based in Pittsburg. She originally trained in ballet, then took some detours before returning to her first love. She publicly came out only recently. Katy Pyle is the artistic director of Ballez, which is a company that “is just what it sounds like… it’s lesbians doing ballet.” Finally, I spoke with two young professional Los Angeles based dancers, Annie Grove and Grace Horrocks. What emerged in these conversations was the systemic erasure of an entire group of artists. All of these dancers circled their way back to ballet after struggling to find their place in the world at large and dance in particular. Although they each had quite individual journeys, there were intense similarities. Almost everyone struggled with body dysmorphia and with eating disorders. They all dealt with perfectionism exacerbated by the perception that who they were was not acceptable. They all struggled with the lack of role models. Bold cites that lack of a role model as a factor in coming out, realizing that her identity is as important to her work as an educator as is her expertise. “No matter what bad things have happened to me, if I can make somebody else recognize any of those problems within themselves and use my pain to stop it, out of a million people, if I affect one, then I have done something…I cannot be the only one. …. I stopped my career too short. I never became a principal in a company. So, I don’t have validity as a dancer–needed to get over that. But in the middle of OK or NY could be this little bunhead who is so confused, who doesn’t understand and I don’t want her to stop her dreams because she doesn’t have anyone to look up to. If I could have seen just one person, even in secret, I would have been able to have some type of ground to stand on.” Both Bold and Pyle dealt with extreme bullying within their dance communities, perpetuated by both teachers and peers. Grove and Horrocks are of the current crop of new professionals, just starting out in the professional world, and while their journeys were shorter, they were no less painful.

There are several concrete harms done by this erasure of lesbian dancers. Because of the emphasis on hyper femininity, eating disorders were universal among the dancers I spoke to, both on and off the record. To be fair, eating disorders are endemic in the dance community, particularly in ballet. Studies show anywhere from 50-85% of dancers suffer from some degree of disordered eating. The difference among this admittedly small sample was their emphasis on femininity rather than thinness. These dancers were torn; they wanted to be feminine, which meant small, but also, the curves that they were fighting helped them fit in, so the anguish was higher. Also, none of them knew what they were feeling or fighting, so control over their bodies was one thing that they could understand. Once again, Courtney Bold, “Before the labels, there was something that made me different. Outwardly I looked so feminine, but there was something clunky and there was something that I wasn’t getting, that wasn’t fitting in with everyone else.”

One theme stood out again and again. Shame. Katy Pyle grew up in Austin “surrounded by lots of gay men but no queer wymyn”. Though she was not interested in men, she did not know that she was a lesbian. She found ballet to “be a safe place to avoid unwanted attention.” She danced both in Austin with The Texas Youth Ballet and Austin Contemporary Ballet and then at North Carolina School of the Arts. There were plusses and minuses in both places. She was bullied “Carrie style” in Austin for being “a freak” but the director of the company supported her strength and individualism. When she went to NCSA the bullying stopped and she “fit in as an artist” however the emphasis on a very gendered approach to dance and “pressure for the waif like, frail dancer” combined with a conscious desire to fit into the ballet department created a serious eating disorder and led her to leave ballet. A “lucky turn of fate” led her to Hollins University and their poetry writing department, though within a week she switched to the dance department. She found her voice, dancing in post-modern and contemporary projects and creating her own work . She stayed away from ballet until she was thirty years old. “The only way I survived was I hid myself. I want the people who cannot hide to be part of the art.” She found, like many of the other dancers that I spoke with, that she had to leave ballet and other established companies to find her voice as an artist and started Ballez in order to give those “shamed out from a young age” their own voice. “Those dancers are super powerful.” Her first project, in 2011 was a regendered production of Firebird. She struggled to find dancers outside of the rigid gender norms of ballet. She needed twelve “masculine of center” dancers and couldn’t find them. “Anyone exhibiting any masculine attributes as a ballet dancer was forced out [of the industry].” It makes her both angry and sad. “This attitude is killing the art form because it makes it irrelevant.” She now teaches inclusive ballet classes in addition to her company work in order to bridge that gap.

Grace Horrocks – Photo courtesy of the artist.

Grace Horrocks and Annie Grove come at this all from slightly different perspectives and experiences. They are both in their early twenties, just out of school and navigating the contemporary dance scene in Los Angeles. Horrocks grew up in Southern California. She wanted to be a ballerina so took classes both at a competition studio and additional outside ballet classes. Nothing else mattered. She bought into “hyper feminine, hyper-sexualized role” as a dancer but “didn’t think about her own sexuality until her twenties.” There was no space for it. She found ballet was a place that she could “fit into boxes while staying in her lane,” using it as “a tool to shove down [her sexuality].” Unlike most dancers I spoke with, she did have a queer teacher in her life. Unfortunately, it was “known but not acknowledged” and led to more repression. Horrocks directly links her anorexia to distancing herself from her own unacknowledged queerness and the signals from her teacher that queerness was something to hide. She later became quite ill, about eight months before she “came out to herself.” This led to another huge identity crisis, especially in terms of ballet. She had so embraced the hyperfeminine. “When I first understood my queerness, I literally thought, how do I do this? Who am I? Clothes, what do I wear, how do I act? I felt too loud, even without saying anything.” She speaks of her recovery from anorexia in terms of both her new body and her queerness.

Grove grew up dancing in a looser environment in the San Francisco Bay Area. She went to University of Cincinnati College and Conservatory as an actor and was “very straight.” She gave me her college headshot as an example of how repressed she was and laughed at it. “Even my hair was straight!” There are parallels to the experiences of all of these dancers: the safety of the ballet world when avoiding the confrontation with their own sexuality, then the break. However, the younger, West Coast dancers have experiences that differ from both Pyle and Bold. They did not have to make a new world but found a community in Los Angeles. Their relationship to that community is evolving and their descriptions of it bounce back and forth between positive and negative. They referred to queerness among female identifying dancers as a “commodity,” that is very specific to contemporary dance, “queerness for the male gaze.” Both Horrocks and Grove say that “queerness makes you ‘cooler’ IF you are hypersexual but NOT in ballet.” Both are growing more confident and secure in their own identities. Both have made their way back to ballet and a newfound love of the art form.

So, what is the next step? Over and over these dancers stated the need for role models. Hire teachers that reflect the population. Representation matters. Trans, gay, lesbian, cis, bi, queer and straight humans all dance. They should teach, choreograph and lead all kinds of companies as well.

Dorsey offers additional concrete solutions:

1. Offer at LEAST one all-gender version of both changing and restrooms. When you only offer “women” and “men” rooms, it puts trans and gender non-conforming people in physical and legal danger. Gendered bathrooms and changing rooms are literally keeping us out of Dance.

- Ballet class – every single class I’ve taken in my entire life only offered 2 binary options for port-de-bras and other aspects of class. And most had gendered dress codes. What is a genderfluid student supposed to wear? What about a non-binary student?

3.Teachers: STOP using “ladies and gentlemen” when you refer to your students. Not all of your students are included by those words. Just stop it! Start saying “dancers” instead.

This idea of language, of the actual words to describe dance, came up over and over. Pearson and Bold both remind us that masculine and feminine are not movement qualities. Strong, light, quick, airy, intense; use adjectives to describe the qualities of a step rather than identifying a particular step as an attribute of gender.

- Partnering: why is it that the world is full of all kinds of human expression and relationships and sexuality, but as soon as we step onstage we are only allowed to be heterosexual? Heterosexual love and pas de deux are beautiful, but SO ARE QUEER ones! Choreographers and teachers stop pretending the world is only heterosexual. Full stop.

Kate Crews Linsley the academy Principal of the Nashville Ballet gives her current approach to the problem. While still in the traditional ballet model, there is space for everyone to grow and train. “As of now, my main focus in this [moving away from the gender binary in ballet] is an attempt to reinvent a training model for our dancers. As the school and syllabus is my main focus artistically at this moment, I want to make sure our training allows space for students to get the focused classes and techniques that they need to thrive as a dancer (ex. pointe class vs. men’s class, partnering, conditioning, etc.) At the same time I want to change the conversation on what students are capable of achieving in class. Everyone needs to work on double tours and saut de basques, to perfect their adagio lines and ankle strength and shape on 3 /4 pointe. I try to teach an “equal opportunity” technique class to make sure that the men are not secluded in the space and women feel encouraged to be as strong and powerful in the class. All genders need to jump at fast and slow tempos, all genders need to do Italian fouettés and a la second turns, all genders need to cross train in the gym. If we develop strength together in the classroom, we are more apt to feel an equal partnership in the creative process in the studio when working in a Company environment.”

Moving out of the studio and onto the stage, representation and media attention is paramount. All of the artists cite the exclusion of artists who do not fit into strict gender lanes. Echoing Pyle, Dorsey states, “It’s been so painful that as trans choreographer I couldn’t hold an audition for trans dancers or have a company of multiple trans dancers. The dance field and modern dance have been so harmful and excluding to trans people that there are extraordinarily few of us trained and working professionally. This is changing now – thanks to the boldness of trans and gender-nonconforming students and dancers, and several allies.”

Yergens adds that identification, like with teachers, is essential. He states, “Dance is a visual field where we look at bodies moving through space, right? So, it’s important to name what bodies we see, and what bodies we don’t see. I think? The appearance of our bodies matter just as much as the self-identification of our bodies because again dance is a visual field. Prioritizing self-identification alone when curating and granting trans, and/or non-binary and/or GNC dancing bodies can be a thinly laid veil for gatekeeping what bodies are “acceptable” and that usually negates bodies that can’t be assumed for what we were assigned at birth as.” He continues, questioning the funding and critical response that is essential to any artists existence. “Are we curating and funding non-cis identified dance artists because we’re transparent about having these artists speak on non-cis experiences and do we respect and honor these artists and see them for who they are? Or are we curating and finding only what we find palatable and cis-normative enough?”

Dorsey continues in the same vein. “For many years in my early career, and still often today, I have to prove the worth and quality of my craft to cis-gender presenters. They don’t start off with the assumption that a trans artist making work that centers trans and queer experience, aesthetics or communities can be technically rigorous and artistically excellent. It’s exhausting having to prove myself again and again when I see cis-gender peers being given the benefit of the doubt again and again.”

So, what does the future of western dance hold? More separate companies or the gradual integration and acceptance of all of the human experience into classical ballet and modern companies? There are tiny fissures of change with specific examples in the ballet community. Dayton Ballet cast both male and female Nutcracker “princes” this past season. Justin Peck cast The Times Are Racing with both male and female dancers in the same roles. For another tantalizing glimpse, I interviewed two amazing moms. Danielle Lucia Schaffer is a lifestyle blogger and mom to four incredible kids, including Instagram sensation Boss Baby Brody. Lori Duran is a writer, blogger and mother to two boys, including thirteen-year-old C.J. who self describes as “a member of the LGBTQ community. My gender identity is male and my gender expression is female.”. Duran wrote a book, Raising My Rainbow and her blog has the same name. Both detail the journey that their family has taken to support amazing artistic children. I asked these moms about the things that make their children unique and how that uniqueness is fostered and protected.

Brody – Photo by Katherine Elaine Photography

Brody, who is all of four years old, has amassed an Instagram following of over 175,000 people including numerous dance dignitaries. His passionate, heartfelt performances sometimes evoke Nureyev, sometimes the Sugar Plum Fairy and sometimes switch back and forth. Costumes include his talented sister’s discarded recital dresses, pajamas (with and without feet) and a signature leotard with the phrase “dance babe.” The first issue that comes up with someone so young is protection; how is Brody shielded from the less kind elements on the internet? “Brody is with mom all of the time and never left alone with anyone. Keeping Brody safe means having a family that will always have his back and support.” But Schaffer went on, with a somewhat unexpected twist. “It also means encouraging him to be exactly who he is.” His safety in the world is predicated upon being fully realized in his own skin. “I honestly have so much support it’s beautiful. I would say 99% of the messages are supportive ones. People are actually inspired by him and he brings so much joy to many. For the handful of negative comments, it seems that Brody’s fans just put them in their place I don’t even need to respond. However, I don’t want people arguing on my page, so if I see any negativity, I just delete it. There is no need for people to be cruel to a four-year-old little boy who is so happy.” As Brody gets older, the outside world could become crueler. Schaffer is clear that they will deal with issues as they occur, especially in terms of sexuality and gender. “Brody is only four and clearly no one knows his sexuality. We will take those conversations when they present themselves. He is so confident and so happy that’s all we care about is that he continues to shine and inspire others.” Schaffer is very open and giving. She understands that Brody’s dance joy is a gift and that many people need it. “When a mom wrote to me and said Brody shouldn’t be allowed to dance and play in costumes, I was so saddened, not so much by her beliefs but at the sheer thought of what kind of person Brody would be if she were his mother. She would repress him from being so awesome. I cried at the thought of some children out there being told what they should do instead of exploring what they love. For Brody, he’s a performer and I will always be the bridge that gets him to where he needs to be instead of the roadmap dictating which direction he should go.” She finished the interview with “We are proud parents of 4 very unique children. And never in a million years would ever think we would be in a position of creating social change by breaking gender barriers. It’s a beautiful thing to let children be who they were meant to be.”

In contrast to Brody’s extreme youth, C.J. is thirteen years old and has already developed a clear and distinct sense of self and a voice to go along with it. He wrote his own blog entry for his mom’s site that is stunning in its maturity and self-awareness. Once again, I had to ask how he is protected from the less supportive or downright mean forces in the world. (C.J. was bullied online by a very famous celebrity). Duran, like Shaffer, is very active in controlling any negative response to C.J, though the age difference is apparent. “C.J. is well aware that there are unaccepting and unloving people out there. He experienced physical and verbal bullying in elementary school. He’s felt the intensity of that. He has not felt the full intensity of online bullying – including when the bully was “famous” and the audience was the entire internet. It’s our job as parents to protect him, so we shield him from hate hurled his way online because he doesn’t need to see it and because it hurts and is damaging. He’s brave enough to want to share his story even though he knows there are haters out there and we are loving enough to not expose him to the specifics of that hate. I don’t give a voice to the haters. I don’t give them the attention, time or platform they are seeking. I do that not only for my son, but also for the people like him and families like ours who might see it. I remove hate from my blog and social media so that it can’t hurt people. We also have a family rule that we never read the comments left in response to articles about us online. In general, it’s very rare that something helpful is said in the comments section.” Duran was also open about the journey, which is something that the dance community needs to embrace. Change does not happen overnight but it does happen. “It was a lifelong journey to get to this place of acceptance, understanding, support and unconditional love. I grew up in a conservative, religious home. My brother wasn’t hyper-masculine like our dad wanted him to be. And, eventually he came out as gay. I watched how our mom and dad parented him and reacted when he came out and I vowed that I would do things differently if I were given a boy like my brother.” She sees her family as educators in a way and honors that position. “CJ has definitely taught us to navigate in a world that is not always kind. He’s taught us that we don’t expect people to understand or know much about gender identity and gender expression, we just hope that they have an open heart and open mind. We are fine with educating people about CJ and people like him. We also don’t want hate to breed hate and fear to breed fear – so we’ve learned to be patient, kind, informational and controlled in situations that aren’t pleasant.”

Much of this article has been about the ways that dance excludes those who don’t fit into strict gender identities. These young people show us that times are changing. Duran shares C.J.’s experience. “When CJ was young, we enrolled him in baseball, flag football and soccer because that’s what boys are supposed to do in their free time. He hated all of it. Then, I signed him up for dance and watched him blossom. I learned that it is my job as his parent to support him in finding his passions. It is not my job to assume his passions.“ C.J. has blossomed IN dance, not in spite of it. There is hope and there is a future. And, if these young people are the leaders, that future is beautiful.

Written by Nancy Dobbs Owen for LA Dance Chronicle, February 26, 2020.

Featured image: Andrew Pearson. Photo by Ben Jehoshua.