In the spring of 2009, I traveled from my home on Oꜥahu to Maui to attend classes led by a tap master of the younger generation, Jason Samuels Smith. As I drove past the pineapple fields and began my ascent up the mountain, my nerves started to tingle, and my palms began to sweat. Would I remember any of the combinations from the day before? Could I keep up with the lithe, younger women in the class? I tried to reconstruct the complex steps in my head until my foot jerked on the gas pedal of my rental car.

“Whoa! Calm down,” I told myself. “It’s just a class. You came here to learn and have fun.”

Finally, after winding up Haleakala Crater Road, I reached the home where the classes were to take place. Driving down the steep gravel driveway, I found a shady spot near the studio, a small room nestled under juniper, eucalyptus and pine trees – trees planted by previous generations of haole settlers.

The studio was located a discreet distance from the main house of a fellow tap addict. From her expansive lawn we could see all the way down the valley with a view of both Kahului on the north to Kihei on the south side of the island.

A small gathering of tap-lovers ranging in age from thirteen to seventy convened for the class. (Tap dancing has no room for age discrimination.)

I sat down on the beautiful wooden floor to tie the laces of my well-worn shoes, purchased a quarter of a century before. Despite the wrinkles in the black leather, the shoes still performed marvelously. Their long journey to Maui had started in a small garage-converted tap studio in Oakland, California back in the 1980s. There they had begun to pick up the subtle rhythms and distinctive style of Camden Richman, a founding member of the Jazz Tap Ensemble. They had tapped with Honi Coles, Eddie Brown and Brenda Buffalino. Dianne Walker once admired them during a master class on Maui. These shoes still produced dulcet tones, so much so that I favored them over the new pair purchased only a year before. Sitting there on the studio floor halfway up Mount Haleakala I remembered back to my first visit to a dance studio, sixty-six years before.

Introduction to the Dance

Main Street, Alhambra, Fall 1943

Though I was born in San Francisco and lived in Berkeley during my first year, my parents had moved to southern California before my second birthday. By the age of three I was ensconced in the house I would call home for the next decade and a half.

Despite the occasional air raid sirens and blackouts, Alhambra was a quiet, predominantly white, lower middle-class suburb of Los Angeles in those days. Until the age of five I had shown neither interest nor aptitude for dance. According to my mother, our pediatrician had recommended the lessons as a means for me to socialize with other children and overcome my intense shyness. I’ve often wondered, however, if it wasn’t my mother’s decision. Having been an amateur dancer in her heyday, she perhaps wanted to see her only child follow in her footsteps. Off to tap class I went every Saturday. It soon became so routine that I believed every child had a similar schedule.

My mother promised to buy me a pair of black patent leather shoes. They look so pretty and shiny on the shelf. When I try them on they feel a little stiff, but oh how they sparkle when I look at my feet in the mirror!

We go to a special shop where metal taps for the heels and balls of the shoes are put on. My mom also buys thick black ribbons. Once we’re home, she threads the ribbons through the shoe holes. I can hardly wait to put them on.

I practice tying the ribbons over and over, but I finally give up and let my mother finish the big, beautiful bows. Then I try walking around with the shoes on. Even though they are still stiff, I experiment making sounds with them, stepping and prancing in different parts of our house. Click-clack. . . The best sounds come when I slap against the wooden floor which separates the carpets in our living and dining rooms. Clunk. . . A more hollow sound happens when I prance around on the linoleum of our kitchen. Clink. . . The taps sound tinny on the bathroom tile and Clonk. . . dullest of all is the sound they make on the concrete driveway. Clonk! Not a pretty noise.

Whether it was a result of the dance classes or my own physical predisposition to movement, at a very young age, like many children, I loved sensations of twirling, spinning and rolling. Also, aided by my mother, I happily practiced backbends, splits and other tricks considered to be part of the dancer’s trade. I loved running with the wind in my hair and climbing our backyard avocado tree was a passion. Despite the fact that I was a tomboy, photos from the time show me to be a small-boned, petite brunette with shoulder-length Shirley Temple style curls, blue eyes and freckles.

Three days later

“Don’t dawdle!” my mom says. The dancing school is above a pet shop. What cute puppies are in the window! Oh, how I wish we could get one.

Mom takes my hand and leads me to a big double door. We enter and are facing a steep stairway. I crane my neck. . . the stairs seem to go up forever. We start climbing. I’m out-of-breath when we reach the top. Now we’re in an office, like the doctor’s waiting room. There’s a desk with a typewriter and telephone.

“Are you Mrs. Egan?” an old lady sitting behind the desk asks. Mom nods. “And that must be Carol,” the lady says, staring at me. I smile shyly and retreat a bit behind Mom. She lifts me up on the bench then takes the new, shiny shoes from their box and hands them to me. I can’t wait to dance in them.

I sit and try to tie my shoes while my mother registers me and pays for the class. Behind another big double door, I hear the sound of a piano playing and someone counting out loud. “ONE and TWO and THREE, ONE and TWO and THREE. . .”

My mom finally comes back and helps me. I still can’t tie the bows and the ribbons seem so long and hard to bend. Once my shoes are on, Mom picks me up and sets me down on the floor. Glancing toward the studio she says, “Pretty soon you’ll be able to do that, too.”

Finally, the door opens and the teacher, Gladys Murray, comes out followed by six kids about my age. After she says hello, Mrs. Murray takes me by the hand and leads me through the double door into the large studio, which is like an immense empty, high-ceilinged cave. I feel very tiny standing in its center. The shoes feel stiff and heavy with their metal taps which sound dull on the wooden floor. An old pianist bangs out routines on the upright piano in the corner while Mrs. Murray holds my hand and bends down toward me. She explains what I should do.

“Step – SHUFFLE – ball-step” she says over and over. The rhythm of her words in no way match those of my feet which resound with a stamp followed by an uneven shuffle and another resounding stamp. It’s really hard to balance on one leg while I try to make the other one brush the floor to make the shuffle sound. A few times my toe hits the floor so hard I’m sure it will be bruised.

“ Ouch,” I mutter.

“Try again, with a little less force,” Mrs. Murray says.

After fifteen minutes of this, it’s time to learn the next step: step, brush, hop! Again, I find the balance hard and wobble as I brush my leg high to the front.

“Not so high. You’ll knock yourself over.” I try repeating the step, this time barely brushing my foot off the floor.

“That’s better,” she says. I feel like I’m just beginning to get it when the lesson is over.

Mrs. Murray tells me to practice my new steps at home and come back knowing them. I promise her I will.

“Next week you’ll join the other kids your age in their class. Remember to practice so you’ll be able to keep up.

The first time I stepped into a dance studio was in Alhambra, California. It was 1943 and the country was at war. I was five years old. From that first day at the Bud Murray School of Dance and for several years thereafter, Saturday mornings were devoted to the pilgrimage to dancing school.

When I had been studying dance for a short time, the son of one of my father’s work colleagues came to stay with us. Our home was about twenty miles from Hollywood and Jack Timmers had come to LA to try his hand at dancing in the movies. He was a handsome eighteen-year old from the Bay Area who was eager to make his mark in show business.

Our yard, 1944

It’s like a dream come true! Jack Timmers is staying with us and he is a real dancer. He’s as tall as Paul Bunyan, his eyes sparkle, and he has such a cute dimple in his chin!

Everyday he spends hours on our phone calling Central Casting to see if there’s any work. Being a movie star takes a lot of time on the phone!

Finally, he gets a job in one of the big MGM musical films. He comes home late at night, so I hardly see him during the week. Sometimes on weekends he practices his routine with me as a partner. We “rehearse” in the back yard, under our big avocado tree. He lifts and swings me high in the air, with my head brushing the lowest branches of the tree. Whee!

I remember the joy I felt as he lifted and swung me high in the air. I loved the sensation of flying. It was every bit as exciting as the kinetic thrill I got from spinning as fast as possible until I keeled over from dizziness.

From my five-year-old’s perspective, Jack looked like a giant. His sparkling blue eyes conveyed his delight with life. It was not mere affect: he was lucky to be alive and even more, to be able to dance. From early childhood Jack suffered from thrombosis, a blood clot in the leg. His pediatrician had recommended dancing lessons to stimulate the blood flow. The therapy evolved into a passion and, by the time he was eighteen, Jack decided to make his living as a dancer.

In the 1940s Hollywood was producing splashy big musical films starring the darlings of the screen: Fred Astaire, Ginger Rogers, Gene Kelly, Judy Garland, and others. Jack’s excellent training, along with his clean-cut, all-American good looks, qualified him for jobs as a back-up dancer. His boyish expression, wavy dark brown hair and impish smile (made all the more irresistible by his dimpled chin) allowed him to find work almost immediately.

Whenever one of his films was released, my whole family piled into the old green Mercury coupe and headed down Main Street to the movie theatre. Once inside, we waited impatiently for the big dance numbers, then yelled with delight “There’s Jack!” as soon as we spotted him strutting or prancing behind Judy Garland or Rita Hayworth or Cyd Charisse. As far as we were concerned, Jack was the star of the show. Needless to say, I was deeply disappointed when Jack found a roommate and moved to an apartment of his own in Hollywood.

Some time later my parents took me to see a local production of “Oklahoma” in which Jack was dancing. With the exception of the Murray’s dance recitals and excluding annual visits to the Ice Follies and Shrine Circus, it was the first time our family attended a stage performance. Unlike the aforementioned annual events, visits to the theatre, considered a luxury which the household budget could ill afford, rarely occurred. “Oklahoma,” presented in a Pasadena auditorium, triggered my love for live performance. It also introduced me to the work of Agnes de Mille. Watching the dancers onstage, I wanted to leap out of my seat in the balcony and join them in the spotlight. Leaving the theatre after the show, flushed and excited, I thought “If this is show business, I want to be part of it.”

My childhood memories evolved around dancing which soon became a very important part of my life. Every summer our dancing school put on a series of recitals, performing in park band shells, for veterans’ groups, and in assorted venues around Los Angeles. Once spring came, our rehearsals began. In addition to the regular Saturday morning classes, our Sundays were also spent at the dance studio.

The large studio had a built-in wooden bench running the length of one wall. During the entire rehearsal, all the students had to sit on that hard bench, even those dancing only in one number. The Murrays demanded absolute discipline. So, there we sat, hour after hour, in complete silence, watching other classes rehearse or looking at picture books, reading, drawing, or doing homework. I especially enjoyed watching the older advanced students doing their routines, and I longed for the day when I would be one of them.

It was probably at those rehearsals that I learned patience and self-motivation. Though it was very tedious at times, in retrospect it seems like the greatest training in the world.

Our first performance of the summer always took place in the park.

Summer, 1944, Alhambra Park

The mothers have been working on our costumes, some make-up has been collected in a small metal box. My mother gets me dressed and made up at home, so I already feel special when we leave the house. Now we’re ready to go.

We arrive at the park and rush across the broad lawn toward the stage. I see the picnickers and park attendants staring at us, and I feel very important. I wonder if any of my schoolmates or teachers are in the crowd.

The bandshell at Alhambra Park offers almost no backstage area, except on the lawn behind the stage. Mrs. Murray hushes us and tells us to be still and try to muffle our tap shoes when we exit and enter. No wings, only a door on either side of the stage. Through these doors all our entrances and exits must be made.

My heart begins beating faster when we start climbing the steps leading up to the door. We listen for our music to start. There it is. . . Mrs. Murray gives the first girl in our line-up a shove and out we go! Those few moments before I am onstage dancing are the hardest. My stomach churns, my eyes blink, and I can hardly catch my breath. But then, in an instant, the worst is over, and I’m out there in the lights, smiling and tapping my heart out. Once again, I feel proud and special. When our number ends and we are offstage again I feel let-down. Why can’t I do another dance?

Sawtelle Veterans’ Hospital, Hollywood, 1944

Tonight, I will make my debut on a big stage. Our class of the tiniest students is wearing gold satin and brown felt “soldier” outfits. Our mothers sewed the costumes. I love the different textures of the materials. I hope the old soldiers in the audience will like our dance. Mom tells me that all the men watching us were wounded in some war. I’m not sure what a war is, but I know it’s bad. It’s the reason we sometimes have to turn out the lights at night and save coupons for sugar and butter.

When we make our entrance from the wings, the huge auditorium, bright stage lights and ghostlike faces in the audience frighten me. After a few moments, however, I begin to enjoy being on stage. When our dance is finished, I long to go back out in the bright lights, but Mrs. Murray quickly ushers us to the backstage dressing room.

Very early on I became addicted to dance. So, it was with great surprise and shock when I heard Mrs. Murray tell my mother that I would never be a dancer because I had no rhythm.

“I’ll show her,” I thought. That may have been the first time I felt determined to prove myself as a dancer.

The Minstrel Show

Around that same time, an incident at my grammar school brought me great shame and embarrassment. LaRee Coyle, one of the other students at the dance studio, was also a classmate at school. She and I had been drafted to perform in our school’s PTA production. That year some woefully politically incorrect parent had decided to put on a minstrel show. (It was an era of complete and utter political incorrectness, so no one really noticed the faux pas).

Emery Park Grammar School, 1945

The worst of my flu is slowly disappearing. I no longer have to vomit all the time, but my nervous habit of blinking is still there. Despite having missed school for over a week, I have to perform in a show on the school’s small stage. LaRee Coyle and I are doing “Way Down Upon the Swanee River,” a dance we’ve already performed several times in our dancing school recitals. Because this year’s PTA event is in the form of a minstrel show, we have been told to dance in blackface.

Tonight, is the performance. My mother and I walk the few blocks from our house to the school auditorium. Once we are backstage, she and LaRee’s mother apply burnt cork to our faces. My hair has been curled into ringlets, just like Shirley Temple’s. Since I got sick with the flu, I’ve lost weight. All my clothes fit much looser than before. The costumes – pinafores over little white cap-sleeved blouse – are no problem. It’s my underpants that give me trouble. The elastic around the waist no longer feels tight. But, no matter, it’s time for us to make our entrance.

Our mothers escort us to the wings, then give us a push when Mr. Bones makes his introduction. The music, played on an old upright piano on the floor of the auditorium a few feet below us, starts. We begin dancing. We haven’t even finished the first verse when I feel my underpants start to slip. I reach down to pull them up. This happens a few times during the dance. Meanwhile I can’t stop blinking, probably due to the bright stage lights. Since my eyelids have no cork on them, my eyes are probably flashing like our car’s turn signals. The audience begins to giggle, then titter. Finally, they can’t control themselves and are guffawing and bending over with laughter. How dare they laugh, I think. I feel angry – no, furious. How dare they laugh at us! I feel like shouting at them to shut up. Instead I keep on dancing, as well as blinking and pulling up my pants, until we are finished. Our number receives the most applause of the evening!

The Minstrel Show incident must have happened just after the war because there was one Japanese American student and a visiting girl from Macedonia at our school. How exotic they seemed to me, and how I longed to be able to speak to the Macedonian girl in her language. My attraction to other races and nationalities probably stems from that time as does my lifelong interest in languages.

The Japanese American girl and I became friends, and she invited me over to her parent’s home. Since she, too, was quite shy, I imagine I was one of the rare friends she brought home to meet her parents who very probably had been incarcerated, along with their daughter, just a few years earlier. Their shyness and reticence to speak to me undoubtably had much to do with their war experiences.

Written by and submitted to LADC by Carol Egan, April, 2020.

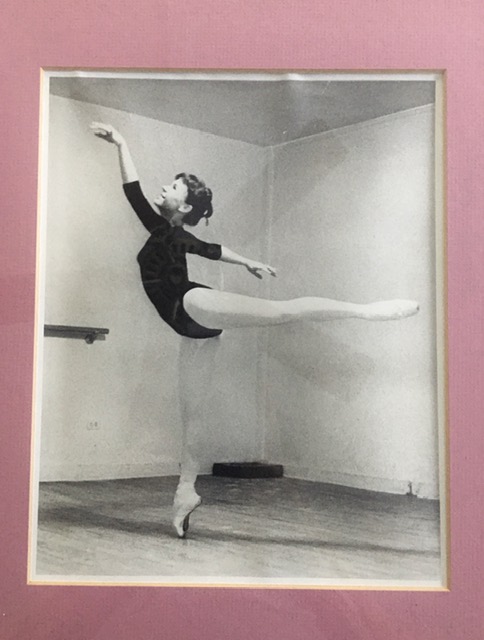

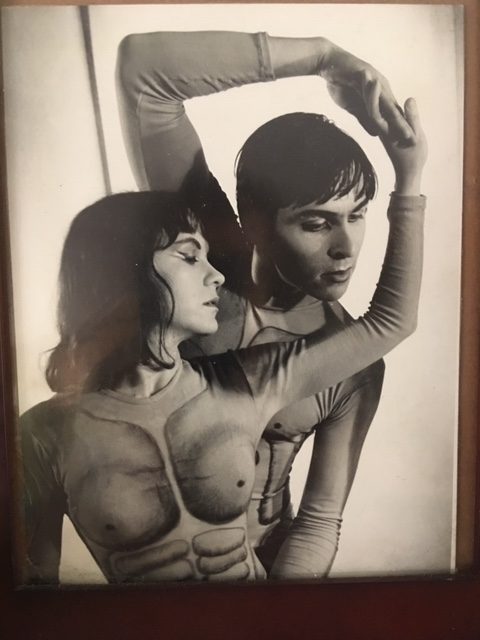

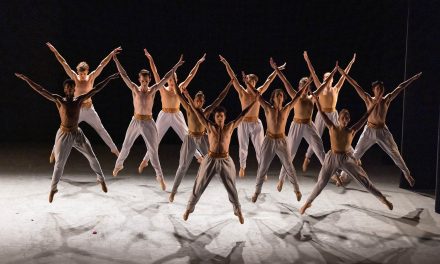

Carol Egan began studying dance at age 5. She trained professionally at the Juilliard School in New York with Martha Graham and Antony Tudor and subsequently danced, taught, and choreographed throughout the United States and Europe. As a dancer, she performed with the companies of Bella Lewitzky, Joyce Trisler, Scapino Ballet in Amsterdam, and the Polish Pantomime Company. Professional companies, as well as university dance programs have performed her choreography in Berlin, Vienna, Amsterdam and the U.S.

Her years of teaching took her to many institutions around the world including the Rotterdanse Dansschool, Smith College, the University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee, Carnegie-Mellon, the Hochschule fur Musik (Vienna), the NY High School of Performing Arts, and UC Berkeley.

In 1978 Carol began writing about dance when she became the San Francisco Bay Area News correspondent for Dance Magazine. She has written for Ballet Review, the Berkeley Voice, and The Honolulu Advertiser, among others, and has managed small dance and theatre companies including the Jazz Tap Ensemble (1980-84).

In 1963 she received a Fulbright Fellowship to study opera direction in East Berlin and in 1965 was awarded a U.S. State Department Specialists’ grant to work with the Polish Pantomime Company in Wroclaw, Poland. Since 2012, she has been training to become an ‘ōlapa with kumu hula, Mapuana de Silva.

*******************************************************************

**If you are a dance professional and wish to submit a writing to “Stories From the Inside”, please also include a short bio, high definition photos, and a head shot of yourself. Send these to info@ladancechronicle.com.

Our policy is: Your writing belongs to you. If we deem it necessary to edit your content we will seek your approval prior to publication. Please only submit content that you know can be published by LADC. There is no compensation for these stories as no one at LADC is being paid for this project. It is a labor of love for our art form.

Feature image: Tap Shoes in Air – photo courtesy Lynn Dally