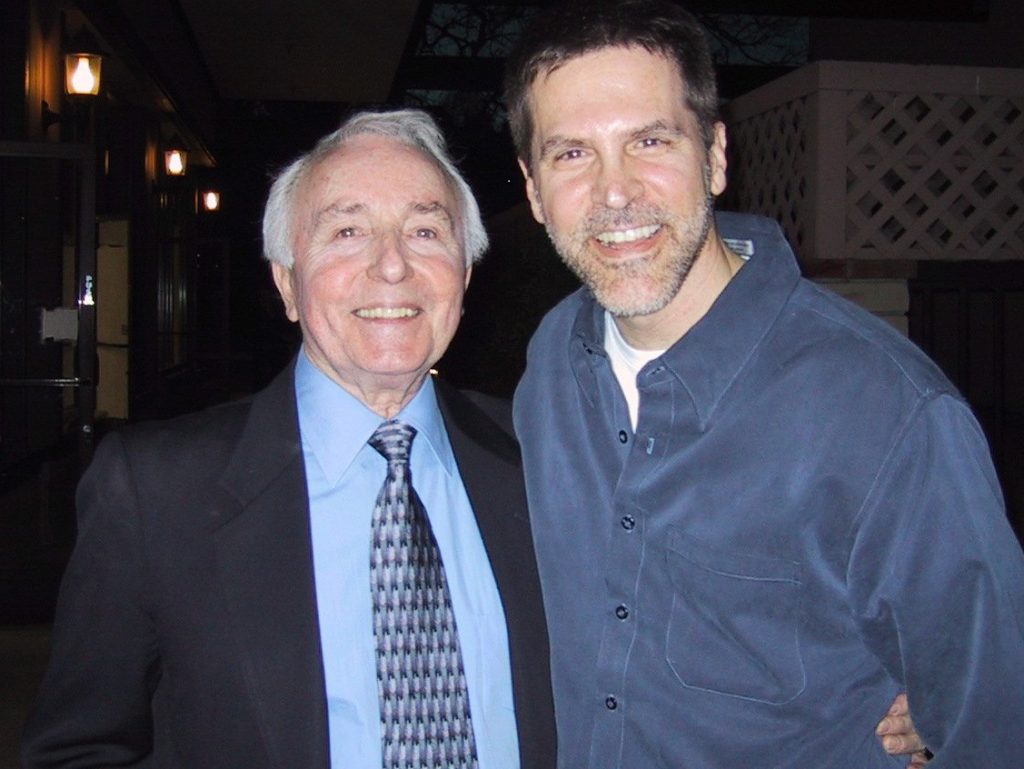

Fifteen years after his death in 2007, my friend Stanley Holden surprised me with an unexpected gift.

As far as I can tell, Stanley left his surprise where anyone could find it. Well, anyone with the intrepidity to do a little research. And if I’m right, everyone missed it. Or maybe a few people knew and didn’t make anything of it. In fact, what I found is absolutely not new. Rather, it’s been hiding in plain sight. What’s puzzling is that my little discovery has never been acknowledged or talked about. It has been long forgotten.

And that’s my point. It mustn’t be forgotten. Nor should the man who gave us this gift.

What I discovered made me sit bolt upright in my chair and shake my head in wonder. After all, I’m neither a dance scholar nor a dance critic. I didn’t expect to find this. Sooner or later, I figured, someone had to unearth this ancient piece of dance history. Apparently I was the only one paying attention.

When I met Stanley in the fall of 1998, the former Royal Ballet principal character dancer, then retired for almost 30 years, was just a ballet teacher to me. I had no idea who he was. In the not quite nine years I knew him, we talked only a little about his dancing career, the characters he portrayed, the famous people he danced with and knew. He told me on many occasions that he prized his teaching life far more than his performing life. In this way, digging to learn more about my friend who died so many years ago is akin to a child making discoveries about a parent long after they passed. I knew some things, but what I did not know was vast.

More than anything else, my discovery reminds me, and all of us who loved Stanley, why we loved him so much. Why we were mesmerized whenever he took the stage, even long after his Royal career ended, when he would come out of retirement from time to time to reprise a role he had made famous at Covent Garden.

I have checked the records as best I can, and have not found any evidence that this little gem, barely seven seconds of improvisation near the end of Act II of La Fille mal gardee, a masterpiece by Frederick Ashton that premiered in 1960, has ever been disclosed or written about. I doubt anyone knows how it happened or why.

La Fille mal gardee was not new when Frederick Ashton decided in 1959 to “recreate the old ballet, which dates from 1789, instead of doing something new,” according to David Vaughn in his definitive chronology, Frederick Ashton And His Ballets. In his hands, Ashton molded La Fille into what the New York Herald Tribune’s headline writer gushed, “Ashton’s Ballet Miracle” upon its American premiere in September 1960.

The ballet was considered a masterpiece even before Ashton brought his reimagined version to Covent Garden. The story’s familiarity and appealing characters have made Ashton’s new staging of La Fille a regular part of the repertory of ballet companies all over the world.

La Fille was not the first ballet to showcase real people in real settings, but according to Ivor Guest, it was the most successful. It broke a mold established in 18th century ballets that focused on gods and heroes and tended toward sentimentality.

“Its characters are as alive today as ever they were,” wrote Guest in a 1960 essay, “and it is perhaps because the audience becomes so intensely interested in them and attached to them that makes so many people return to see the ballet time and time again.”

La Fille mal gardee, translated as The Wayward Daughter, is a story about a farmer, the Widow Simone, and her daughter, Lise. The Widow schemes to marry Lise to Alain, the dimwitted son of a wealthy local vineyard owner, Thomas. Lise, however, is in love with Colas, a young farmer in the village.

If I am correct, Stanley spoke on the record about his bit of ad-libbing only once, in an unpublished interview he gave to the late dance writer, Tobi Tobias in 1978. Which I unearthed in the archives of the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts and read more than 40 years later.

Holden danced many parts in his 25-year career with the Royal Ballet. The list is long and substantive: Puss ‘n Boots in The Sleeping Beauty, Gopak in The Nutcracker, the Elderly Gentleman in the Assembly Ball, Mr. O’Reilly in The Prospect Before Us, Pierrot in John Cranko’s Harlequin in April, David Hew Steuart-Powell in Enigma Variations, and Dr. Coppelius in Coppelia, among others. Arguably his most famous, and beloved, is the irascible but big-hearted Widow Simone in Ashton’s La Fille.

The part has always been danced by a man since its creation in 1789, who undergoes hours of make-up and costuming, and tries his best to recreate Stanley Holden’s magical, nuanced interpretation. Holden debuted the modern version of Widow Simon more than sixty years ago, and in the eyes of many, he established the gold standard for others to emulate.

Most try to fill his dance shoes, but few succeed.

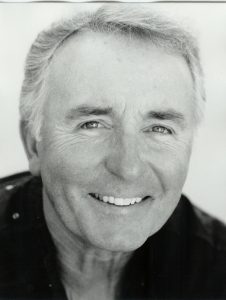

Philip Mosley, who joined The Royal Ballet in 1986, spoke with me in a Zoom interview. He is one of the more successful contemporary character dancers to dance the part of the Widow Simone. I asked him if he was aware of Holden’s ad-libbing in 1960.

“No,” he said, a little startled at the news. “Really? I always have fun with that scene, but I didn’t know how it came about.”

A scene from La Fille Mal Gardee by The Royal Ballet – Philip Mosley as Widow Simon – Photo ©Tristram Kenton

In the 1990s, more than a decade before Youtube, Mosley had virtually no access to archival footage of Stanley’s antics as Widow Simone. When he first saw the BBC recording, he was struck by two aspects of the performance.

“Stanley was more animated,” he said, rapidly tilting his head side to side, imitating Holden, in describing what he saw in Holden’s Widow. “And his facial expressions, too. Made me want to do a bit more than I was doing.”

Stanley understood his character. But how did he understand? I asked his oldest friend, a woman with whom he attended ballet classes in their early days together with Sadler’s Wells Ballet, later becoming what we know as The Royal Ballet. Margaret Graham Hills was a promising young ballerina until a career-ending knee injury. She transitioned to become the assistant to the company’s artistic director, Ninette de Valois. She knew Stanley perhaps longer than anyone outside his family. And she had thoughts about how Stanley evolved a character.

“He was a stickler, and he wanted everything right,” said Hills, “and didn’t like it when things weren’t as he’d hoped. But his training hadn’t made him able to explain why a step should be like that. He just knew it should, but he couldn’t explain why.”

Stanley shared a story with Victoria Koenig, co-founder and artistic director of the Inland Pacific Ballet in Claremont, California. She collaborated with Holden in 2001 and 2003 on Coppelia, when he came out of retirement for the last time, to reprise his role as Dr. Coppelius, the doll maker who brings a doll to life. The story he told Koenig took place when he was young, living in East London. “I used to take the bus to the studio,” he said. “And I would take notes. You see, you can’t make this stuff up. I took notes about what I saw people do on the bus. Their mannerisms.”

All of which he stored away and drew on.

Then I asked another old friend, a man who knew him for more than 40 years, if he could shed some light on Stanley’s gifts. Edward Villella is a native of Queens, New York, and in his youth was a champion boxer, lettered in baseball and earned a college degree in marine transportation. Like Stanley, Villella devoted his life to classical ballet, becoming first the international star of New York City Ballet under George Balanchine, then the founder and artistic director of the Miami City Ballet. He is considered the most celebrated male dancer in ballet of his time.

The two men lived an ocean apart in the early years but were not so different. Stanley was the poor Cockney lad, the youngest of eight children. Villella, a few years younger than his English friend, was a working-class kid who climbed to the pinnacle of the rarified world of ballet. Both discovered dance by following a girl to dance classes — Stanley took tap lessons in the late 1930s with his first love, an eleven-year-old, blonde-curled beauty named Iris Powell, and Edward found ballet with his older sister.

“‘Why?’ was the most important thing,” Villella said he asked himself of every role he performed. “Not too many people worry about that today … You could create almost anything if you had the knowledge and the understanding.”

He saw the same inquisitiveness in his friend.

“Not only did he show you something (in his characterizations), but he was showing you a new aspect of that particular role, his own take on that particular role. So he was a genius from that point of view.”

For many years, The Royal Ballet would travel to New York and perform at the same time as City Ballet, and the two companies sometimes attended each others’ performances. This is how Stanley and Edward met. I was not surprised when both men confessed to similar emotional responses after a performance. I think they spoke for all performers who commit to their roles with every fiber of their being.

“I needed two, sometimes three hours to come down,” Edward told me in 2008, almost 30 years after his retirement from City Ballet. I had asked him what it was like to dance a piece by Balanchine. He was sitting in my car as I drove him to LAX to catch a flight back to Miami. I couldn’t see the look on his face, but the matter-of-fact tone of his voice was tinged with nostalgia, as if he were remembering a friend he hadn’t seen in a long time.

Stanley pulled no punches when he spoke to Tobias about his post-performance state-of-mind. Although I was reading words on a page, I could hear the melancholy in his voice.

“I hate coming out of the roles,” he said. “Hate it. It takes me a while. I would very much like to come off, go into a plain dressing room, sit there for a while and unwind that way. I find it very depressing coming out of the role.”

In public, and to me privately, Edward described his “pal” Stanley as a drinking buddy. When they were in New York at the same time, and after one or the other’s performance, they often went out on the town, very late, to relax.

“One of the first memories I have of Stanley,” said Edward, “is us going down to somewhere around 42nd Street, and we went bowling. That’s the worst thing a dancer could do. Take this big, huge thing and throw it down an alley and then let go. Your back just goes crack.”

Bowling? The image of two international ballet stars hanging out at a bowling alley is, well, incongruous.

“As a dancer you also have to have a good time,” said Edward. “You have to have a release from the incredible discipline that is brought to the art form.”

Seven seconds of improv. You could easily dismiss them, the necessary, some might say unavoidable, fillers for human error. True enough. Except for one important difference: Every dancer who has ever portrayed Widow Simone since Holden added his brief improvisation on January 30, 1960, incorporates his seven-seconds. That gem is part of the canon, the accepted Ashton choreography presented by ballet companies everywhere.

No one, apparently, is the wiser.

And in typical fashion, Stanley Holden, the comic genius, the man whose skills as an empathetic character dancer were compared to Charlie Chaplin’s, has had the last laugh. Decades after he left The Royal Ballet to come to Los Angeles and embark on a new career as teacher and mentor, and fifteen years after his passing from colon cancer and heart disease at age 79, Stanley Holden delights and surprises us to this day.

Stanley and I had become friends when I asked him to choreograph a short piece of ballet for a new choreographers’ showcase I launched in 1999 called the LA Dance Invitational. The next year, he joined our adjudication jury, and then for five years until the year before his death, he and our team waded through the annual submission of dozens of videos from all across Los Angeles and eventually the US, to select dance companies and choreographers for each concert.

On a few occasions, I played pool with Stanley at his home in Woodland Hills, a suburb of Los Angeles. During these friendly games, I learned that pool had been a central part of Stanley’s life when he was growing up in London. When he was young, he earned money this way.

The game almost derailed his dancing career. He was drawn to tap at the age of 11 after watching Fred Astaire and found a weekly tap class near his home in London.

“Astaire was, to me, the classicist of all time of dance,” said Stanley.

The youngest of eight children, he and his siblings moved from Shoreditch to Romford, neighborhoods in London, and his mother took him to the Bush-Davies School of Dancing. His instructors advised that he expand his training to include classical ballet.

“I loathed it,” said Stanley in his interview with Tobi Tobias, of his ballet classes. “I’d miss class and be down the pool hall. I would never miss the tap classes. But suddenly I’d think, ‘Stupid, I’m here with these tights on and I could be earning money down in the pool hall!’

“I mean, that was my motivation at the time, towards ballet,” he said.

He was almost fourteen when something clicked.

“…I suddenly got the dreaded disease,” he said. “And it is a disease, you know. It’s not an art form, ballet. It’s a disease. It’s a wonderful disease to have, but it is a disease. There’s no question about it. You can’t get it out of your system. It just grows and grows and grows.”

About five years passed between his first tap classes, and when he “came down” with ballet. At the age of sixteen, he passed the advanced Royal Academy of Dance examination, and was offered a spot in Sadler’s Wells Ballet Theatre school. Except for required military service in 1948, and time in South Africa to teach in the mid-1950s, he remained with The Royal Ballet until his retirement in 1969.

“I was classically a very good technician, for that time,” he told Tobias. “I used to do eight, ten turns, good turns, in those days. But I never did it on stage.”

He wanted to dance classical roles.

“I wanted to play Hamlet,” he said, “like all comedians do. I was labeled a comedian the moment I started with the company, with the kids. I was the jester in the classroom.”

His Royal Ballet School teachers had other plans for the young jokester. His dream of dancing a pas de deux in Giselle would not come true.

“I did not resent (my teachers) for it,” he said. “I was sad about it because I would like to have proven that I could have done it. I was fortunate because I had something else.”

The something else meant, he realized, that he never wore tights on stage.

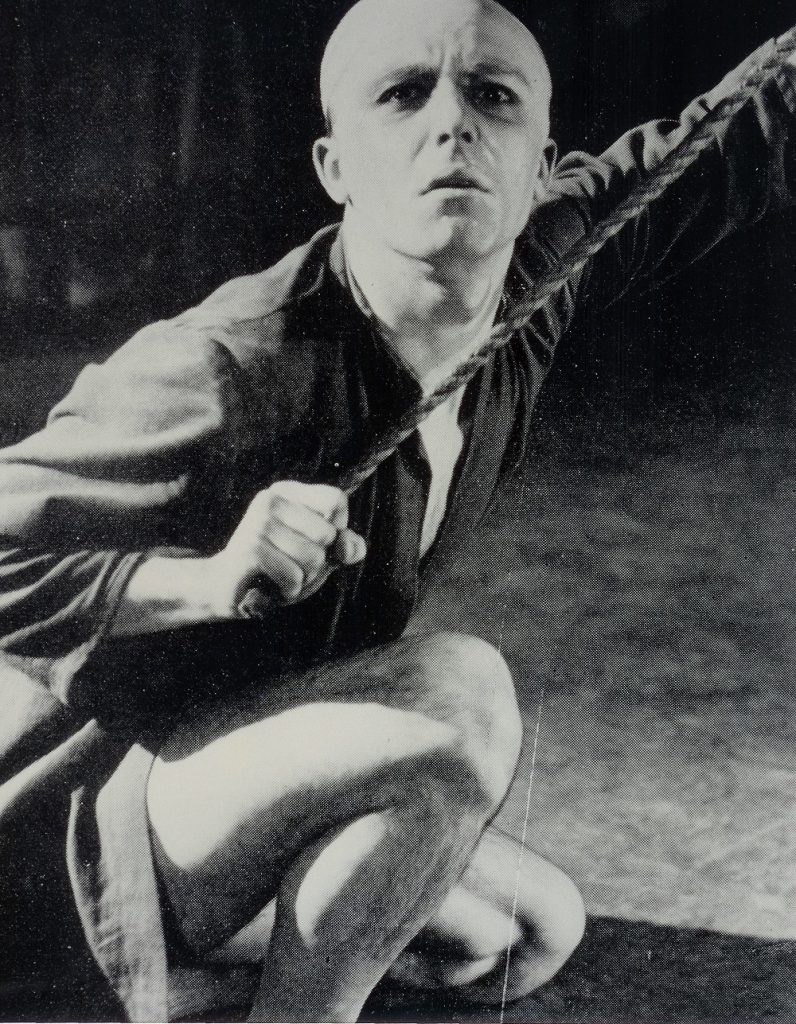

Instead, he donned the costumes of characters who touched the hearts of ballet fans everywhere. One of his earliest was a modern twist on a sad-clown character whose origins date to late 17th century Italy.

“I did Pierrot in Harlequin in April, for (John) Cranko,” Stanley said to Tobias, “which was a wonderful masterpiece … one of the best ballets I’ve ever done, for me personally, selfishly. I loved the ballet for myself, as Pierrot.”

Cranko and Stanley were five months apart in age. Cranko joined the Sadler’s Wells Ballet School in 1946. In 1950, he was named resident choreographer for Sadler’s Wells Dance Theatre at the age of 23, and his first work for the company was Harlequin in April, in 1951.

LA FILLE MAL GARDEE , Stanley Holden (Widow Simone) – Royal Ballet, Covent Garden, London, January 1960 – Credit: G.B.L Wilson / Royal Academy of Dance / ArenaPAL

Critics loved Stanley’s character as well. Wrote John Martin in his March 29, 1952 review in the New York Times, “Here is a work of fine imagination, poetic texture and sturdy choreographic substance for all its delicacy … and Stanley Holden (is) a beautifully stupid and meaningful Pierrot.”

Stanley’s path to Widow Simone in La Fille mal gardee was anything but clear or easy. He almost did not get the part. In fact, he was hoping to do a new ballet for John Cranko and had received permission from de Valois to take a leave from Sadler’s Wells for this opportunity.

The story Stanley told to Tobias revealed both the inner workings of the Royal Ballet and Stanley’s dogged patience. In late 1957 he had returned from South Africa, healed from a foot injury and a stint as a ballet teacher. He left as a principal dancer with Sadler’s Wells, and when he returned his former company had transformed into the Royal Ballet when a Royal Charter was granted in 1956. But Stanley did not return as a principal. By tradition, inexplicably, he was relegated to the corps de ballet. He was not happy, and in his interview with Tobias, you can hear the disappointment in his words.

“I walked on with a trumpet for six months,” he said, chuckling at the memory of his situation.

He did what he was told, displaying his true British stiff upper-lip.

“I think one’s destined,” he said. “I believe in fate quite a bit. I believe if they say, ‘You stand there with a trumpet for six months’ — you resent it. I resented it like crazy, but I’m standing there for a reason because as soon as chance came, I took it.”

Stanley had already started rehearsing John Cranko’s new ballet, called New Cranks. Widow Simone went to Robert Helpmann, the renowned Australian dancer and actor. But Helpmann backed out after one rehearsal. de Valois then changed her mind about releasing Stanley.

“So de Valois called me to the office and said, ‘I’m going to keep you to your contract.’ I said, ‘What do you mean?’ She said, ‘You can’t do New Cranks.’ I said, ‘But you gave me…’ She said, ‘I’m going against my word, but I need you for Fille mal gardee.’”

Cranko, according to Stanley, flew into a rage and tried to talk de Valois out of her decision. She refused.

“The next day,” said Stanley, “I was in that rehearsal room doing the second rehearsal (for Fille). Of course it was all in the … press, saying ‘Holden takes over for Helpmann.’

“I mean I was a nobody,” he continued, “and suddenly I’ve got headlines.”

But he said he believed in fate.

“And New Cranks was the biggest failure, a miserable failure,” said Stanley. “They had to bring it off (close it) after a week, I think.”

Widow Simone was, for Stanley, a career defining role. Wrote the dance critic and former ballet dancer Fernau Hall, “One facet of the role developed through the relationship of Lise to her mother—a relationship which is fundamental to the action. Mother Simone, in Stanley Holden’s superb interpretation, is a lovable creature. Holden is a marvelous comedian, and … he made Mother Simone’s humor subtle rather than crude. Partly he did this with his superb timing, transforming slapstick gags into something poetic, almost Chaplinesque.”

Walter Terry, writing in the September 16, 1960 edition of the New York Herald Tribune, said, “Stanley Holden, thoroughly disguised as Widow Simone, gave a comic performance of such brilliance that it came close to stealing the show…”

Stanley was often compared to the pantomime dames and the British music-hall comedians, the over-the-top drag artists, in his depiction of Widow Simone. He never cared for the comparison.

“I like to feel, myself,” he said to Tobias, “that I’m not a man in drag. I want to feel that I’m a woman. That, to me, is acting, and this is always what I’ve tried to be in La Fille. I want to be Widow Simone.

“She was lovable, very strict, but very lovable. Humorous, to a point, without her knowing she was funny.”

“He never tried for a laugh,” said Margaret Graham Hills. “What he did caused a laugh. It’s a subtle difference there.”

She recalled a scene in Fille, where Stanley as Widow Simone noticed a drawer in a chest of drawers.

“He saw that it was open, so he backed up on it and shut it with his bottom. He didn’t make a fuss about it, but it was hilariously funny.”

I have watched La Fille mal gardee in its black and white BBC version twice, and snippets of it many times. Stanley is charming and endearing, but what stands out most in his performance is something I sense because of what he projects through the screen: He is always in the moment. He knows precisely who he is on stage and inhabits Widow Simone entirely. And that explains, perhaps, why the seven seconds of improvising I stumbled upon was seen as what she was supposed to be doing, and not as a mistake.

Stanley, it seems to me, fooled us all.

Seven seconds of improvisation whose origins have been hidden from the ballet world is not the equivalent of discovering a new Shakespeare sonnet. But it is still a thing to marvel at.

David Vaughn, in his Frederick Ashton And His Ballets, says nothing about these handful of seconds Holden used to laugh-out-loud effect. Or rather, Vaughn accurately describes what transpired in those seven seconds, but only in the mistaken belief that the scene he describes had not been improvised. In other words, Vaughn was clueless.

The stacks of reviews of La Fille I have read from 1960 say nothing either.

I uncovered Stanley’s revelation when I was researching his life and career. In his interview with Tobias, Holden answered a question about how he develops a character.

“They build,” he said. “Your performance builds from actually performing, something you can’t do in a rehearsal room. If you could film my first performance and film my performance (much later), I think there would be a great difference. Lots of things are put in by accident.”

What happened?

He lost track of the count and missed his mark.

Holden was alone on stage when he was temporarily befuddled, near the end of Act II of La Fille. Frederick Ashton’s then-new ballet had premiered two days earlier, on January 28, 1960, to adoring audiences, and warm but not rave reviews.

A.V. Cotton wrote at the time: “…no new ballet in the post-war repertoire at Covent Garden has so swiftly ingested its initial faults and imperfections and acquired that sense of inevitability that any good stage plot must have.”

Writing for ballet.co.uk, Jane Simpson says of the first performances, “Osbert Lancaster’s scenery disappointed some: Alexander Bland described it as ‘knowing,’ and thought it mocked at Ashton’s conception; others found the ribbons and all the other props a bit much; and there was some doubt as to whether Widow Simone was too much of a pantomime dame.”

Yet Ashton never doubted. According to Vaughn, the choreographer was known to have become physically ill on the opening night of a new ballet. Walter Terry, in the September 15, 1960, edition of the New York Herald Tribune, knew his subject well when he wrote, “Frederick Ashton … trembled before and during the London premiere of his ‘La Fille mal gardee’; he trembled when foreign critics viewed it at the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden, and presumably, he trembled last evening when ‘La Fille’ was given its American premiere by the Royal Ballet at the Metropolitan Opera House.”

But according to Vaughn, Ashton felt no such ill effects at opening night of Fille.

A scene from La Fille Mal Gardee by The Royal Ballet @ Royal Opera House – Philip Mosley (center) as Widow Simon – Photo ©Tristram Kenton

Audiences fell over themselves cheering the new work by Britain’s acclaimed choreographer. Critics may have chewed their lips over details, but opening night produced nineteen curtain calls, including five after the house lights had been turned on, according to Ivor Guest in his essay, “The Saga of ‘La Fille mal gardee.’” Seventeen curtain calls erupted after the second performance, and fifteen following the third.

“He was like a stand up,” said Inland Pacific Ballet’s Vicky Koenig. “He was a great improviser.”

Improviser yes, but also an exacting professional who rarely made mistakes.

“He could recreate each moment precisely, the same way, every single time,” said Koenig. “And make it real. There was no approximation. His timing, the gesture, the attack, the eyes, the look, everything about (a role). He was masterful. It was really an extraordinary experience watching that.”

But there he was, on stage at Covent Garden in only the third performance of Fille, and he knew he was not where he was supposed to be.

Principal dancers on the Royal Ballet were known to be envious of Holden because they knew Ashton often sneaked into a performance, sometimes halfway through, to watch the mischievous character dancer when he was on stage.

“When (Ashton) knew I was out front,” recalled Stanley in the Tobias interview, “he used to say to me, ‘What are you going to do tonight?’ I’d say, ‘I’ll wait and see.’”

“He’d whoop and holler,” said Koenig of Ashton, “and then leave. All the principals who were dancing these three-acts ballets would be resentful.”

Whether Ashton was in the audience on the third night in January 1960 and watched as Widow Simone acted her way out of the conundrum is not known. But there is little doubt he would have whooped and hollered.

“…something happened,” admitted Holden in his interview with Tobias. He also admitted that he did not know the answer. But oh what he did with seven seconds.

What the record shows comes to us from two sources. The first is David Vaughn whose book was published originally a year before Holden sat down with Tobias at the Brooklyn Academy of Music. Vaughn’s revised edition, published in 1999, did not change the description of Holden’s performance. It did not include Holden’s revelation of his miscalculation, so the author recounts the version of La Fille as it was performed at Covent Garden after Holden’s ad libbing.

Vaughn was oblivious to the change. He described the dancer and the scene:

“[Holden] reminds one of the great comedians of the British music-hall, such as Nellie Wallace or Dan Leno, the famous ‘Dame’ of late Victorian,” he wrote, “artists whose comedy depended not on telling jokes but on characters created out of close and loving observation. Holden has the impeccable timing of such performers: (referring to La Fille) hearing the approach of Thomas (Alain’s father) and Alain, Widow Simone goes to the mirror to fix her hair before opening the door – then darts back for one extra look of pure self-approval.”

Vaughn’s portrayal is expertly observed and accurately recounted. Any viewer of the black and white video of the ballet, recorded by the BBC almost three years after the premiere, sees what Vaughn described. And the video is the second source of what we know about the ballet…that Holden changed unintentionally.

“And every performer in the role,” said Holden almost 20 years after his first performance, chuckling at the memory, “adds that bit in now.”

What bit is he referring to?

In the second act of La Fille, the Widow Simone and her daughter, Lise, await the arrival of Alain, the man the Widow wants her daughter to marry. However, Lise has fallen for Colas, a local farmer, and the two secretly hope to marry, against the wishes of her mother. While the widow is away, locking her daughter in their house, Colas appears unexpectedly. Soon, they hear the Widow Simone returning, and Lise hides Colas in her upstairs bedroom. The Widow Simone orders Lise to put on her wedding dress for the imminent ceremony, and when she refuses, her mother pushes Lise into her bedroom and locks the door.

Soon, Alain and his father approach, along with a notary, to sign the marriage contract.

Here is where Holden added his bit.

Alain and his father, Thomas, approach the Widow Simone’s house. The Widow is descending the steps after locking Lise in her bedroom, then turns and approaches the front door.

“I got to the door too soon,” said Holden of his performance on the third night. “I rushed. I thought, ‘If I open the door now, it’s not going to be correct.’”

He had missed his mark.

“I suddenly remembered there was a little mirror back around the alcove,” Holden said. “I went back there and did a sneaky look ‘round the corner. I got into a sort of low arabesque, and touched up my hair…”

He did not pause at this moment in the interview with Tobias, and he should have, because what he added next is what audiences remember most.

“… and gave myself another look.”

Remember how Vaughn described it: “…then darts back for one extra look of pure self-approval.”

During our Zoom interview, Philip Mosley demonstrated this very moment by standing up, walking off camera, then leaning into view at an angle, substituting the computer camera for the mirror on stage. Then he primped his imaginary wig, and darted back off camera, leaving behind the indelible memory of his ear-to-ear grin of “pure self-approval.”

Precisely as Holden described it and danced it. Straight into the history books.

“Well,” Stanley recalled to Tobias, “I mean the audience went crazy.”

A simple gesture, but human and humane, conjured in the moment by a master of keen observation.

Holden called these the “best moments.”

“You’ve had to ad lib, and they’ve had to stay in (subsequent performances) because they were so successful.”

Did anyone even know?

“Oh yes,” said Stanley. “They watch every performance. I mean every performance they’re there. Your staff is watching you.”

And we know now how Stanley’s momentary lapse altered a masterpiece. The ballet acquired seven seconds of new choreography that has remained unchanged to this day.

The audience went crazy. Four words that summarize the ballet world’s universal response to “the finest and funniest comedian produced by the Royal Ballet School,” according to the Times of London.

* * *

I was standing in a parking lot in Minneapolis on a warm May afternoon in 2007 when the call came from Jamie Nichols, a friend and renowned choreographer and teacher in Los Angeles. It was bad news.

“Stanley died yesterday,” she said.

“What?” was all I could muster. I had been digging in my pocket for my car keys, then had to dig in the other for my phone. I was a little distracted.

Jamie shared what she knew: heart disease, colon cancer, in a hospital, lost consciousness, fell into a coma. He passed quietly. He was 79.

Six months earlier, I had flown back to Los Angeles to celebrate my 50th birthday with friends, and Stanley and his wife Judy were there. They were all smiles, making jokes, laughing. Stanley looked pale, his hair a little thinner, but he said nothing about poor health. It was the last time I saw my friend.

A few days after Jamie’s call with news of Stanley’s passing, I retrieved the New York Times from my doorstep. I found his obituary, to my surprise and delight. It was accompanied by a photo of Stanley in a familiar pose. He was sitting on the floor of the dance studio bearing his name in Los Angeles, probably taken in the 1980s, an arm draped casually over one knee, wearing black dance shoes, jeans, a striped shirt, instructing dancers whose reflections were visible in the studio’s mirrors.

Stanley Holden was my friend and colleague, a man whom I knew fewer than nine years, the last years of his life, so to see his image above two columns of copy in the obituary section of the venerable Times made me feel proud, but almost as quickly, I was plunged into sadness. The reality of his death hit me hard.

He’d told me once, in a conversation years ago, about meeting Charlie Chaplin, a boyhood idol. He was 24, in Chicago, when he met Chaplin backstage. They were both Cockney and lived in the same part of London. They talked about growing up in poverty.

“If I’ve gotten anything from Chaplin,” he said to Tobias, “it may be his subtlety, which I’ve tried to be all my life.”

We never laughed at Stanley Holden. We always laughed with him. He knew us, sometimes in ways we did not know ourselves, reflected to us through the characters he portrayed on stage. He could make us laugh and he could make us cry. Which is why he was compared to Chaplin.

I miss my friend. But only now, 15 years after his passing, has Stanley revealed to me what he meant by subtle: Seven seconds the ballet world will never forget.

Written by Howard Ibach for LA Dance Chronicle.

Featured image: Stanley Holden – Photo courtesy of the author.