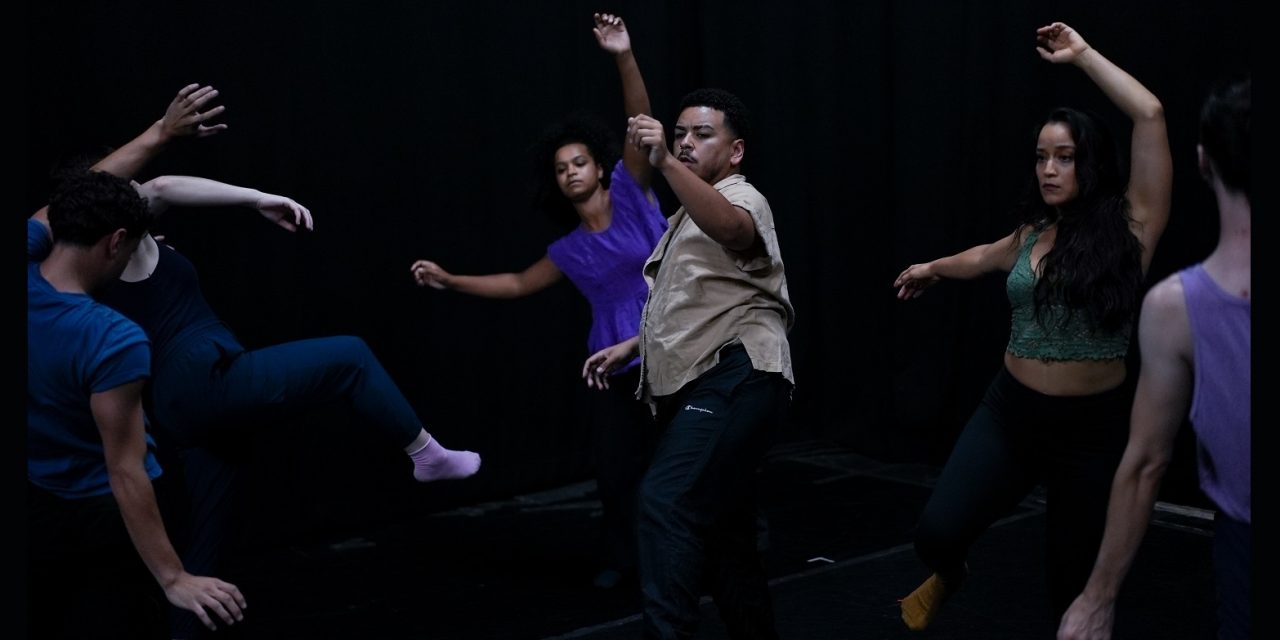

Andrew Pearson is looking for a way to distribute ownership of dances. He is working on an untitled collaborative project where everyone owns the movement and the making — with collaborators Darby Epperson, Sadie Yarrington, Cristina Florez, Daurin Tavares, and Derrick Paris.

Pearson has been working to reimagine the model of choreography and collaboration. He pictures a completely horizontal leadership model, facilitating a process that dismantles the director’s hierarchy and shares ownership of the work.

“In the dance world, collaboration often mean[s] that the dancers make up all the work and the directors put their name on it. It seem[s] imbalanced, even when it says, ‘choreographed by dancers,’” he shared.

Western traditions of the dance industry are so deeply rooted in the hierarchical model that even Pearson’s intent to work against it is a statement. And so to put this ideal into practice involves constant untangling, unlearning, discovering, adapting. Pearson was in residency this summer as a graduate student: a professor suggested that he make a solo simply to observe himself in process, to evaluate the process and dissect his own creative tendencies.

Laying the groundwork

Around the same time, Pearson was also surveying collaborators and audiences. Epperson and Yarrington remember answering deliberately transparent questions: how much would you want to be compensated for a project that involves this much time and work? What are our shared values as a community? As an audience? As contributing artists?

When it came time to assemble the team, they already knew that community needs would be prioritized. Not only was this process searching for a horizontal model; it was also open, flexible, seeking input from all parties. Pearson reached out to Epperson, Yarrington, and Tavares — all previous Bodies in Play collaborators — and invited them to nominate another cast member. Epperson invited Paris, and Tavares invited Florez, and both met with Pearson before coming on board. Due to logistics, Yarrington couldn’t bring in cast member, but Pearson suggested she take on a role as co-creative director as a way to claim some ownership of the project.

“We’re all so used to defaulting to our roles…this space kind of dictates that, because that’s what we’re used to stepping into in this space,” Epperson said.

“We all had many roles,” Yarrington responded. “Being a dancer in this project meant so many things…it meant everything.”

What the room looks like

Once they were in the room, Pearson brought body and identity-based prompts to the rehearsal and then allowed them to fall away. For three weeks, the team worked in two-to four-hour rehearsal periods, each with an open warm-up period at the beginning.

The collective filmed the entire process, and Yarrington essentially watched all the clips and pieced them into a sequence before their work-in-progress showing in October. They found that the themes of the process naturally asserted themselves in the work.

“To make sure everyone felt seen and valued in the performance, just like they did in the rehearsal process — that was important, too,” Yarrington shared. “It was very much about our individual bodies, and how these bodies share space and time together.”

“This is probably the first production I’ve been a part of that was completely process-oriented,” Florez said. “This always felt like, what we’re doing right now, the collaborative process, that was the goal.”

Also exciting was the great possibility that these clips in other arrangements could yield entirely different outcomes. But no matter the sequence, the collective found it immensely gratifying to dance as a unit of individuals in a work that was everyone’s.

A study in audience participation

There seemed to be a mutual feeling, an alleviated pressure on the day of the showing: this was just an invitation for audiences to share the process.

“It was also really liberating and freeing to just say, ‘We made some really cool work. Let’s invite people into that process…I don’t think people realized how possible it was until we showed them,” Epperson said.

“And it was so exciting how many audience members wanted to share,” Pearson explained. He had questions prepared to facilitate the talkback, but the lively conversation sustained itself. Ideas and feedback were willingly volunteered, perhaps because the room felt still open to ownership, to process. The threshold for input had expanded.

Next steps

The team is still learning from the experience that was the work-in-progress showing and regrouping and fundraising to support the next leg of this process, whenever the resources are available.

Now, Epperson is more conscious about the work she steps into, asking whether it will serve or stifle her and holding her boundaries more firmly. Florez is learning that having feelings is okay, even for professional dancers; that she has agency to change or leave a process. Yarrington is considering that to-do lists are common, but not-do lists — of things that do not align with your values — can also guide a creative process in the right direction.

Pearson is learning that ownership and leadership are not necessarily the same, and that together a good team can accomplish so much. Tavares and Paris were not present for our interview, but their physical and mental presence in the work was very much felt throughout our discussion.

In the new year, Bodies in Play will see two presentations of Pearson’s solo Abbale, as well as a 2023 fundraiser to support more iterations of this work. Pearson and Epperson both contributed to Stomping Ground’s annual Urban Nut and brought the ethos of this process into that rehearsal room to continue researching and distributing agency. If we are lucky, maybe we will catch another work-in-progress soon.

To learn more, visit the Bodies in Play website.

Written by Celine Kiner for LA Dance Chronicle.

Featured image: Bodies In Play – Photo by Winnie Mu, @winniemuvisuals