Los Angeles Ballet, now in its thirteenth season, presented a two-part program at CAP UCLA’s Royce Hall this weekend: in the first act, George Balanchine’s quintessential Serenade. And in the second, a stark contrast: August Bournonville’s La Sylphide. Though the romantic and neoclassical eras seem far removed, the two paired quite well. For better or for worse, the ethereal, wispy feminine trope seems to have drifted through the classical ballets and into Balanchinian mythology. In this particular Saturday evening performance, principal Bianca Bulle carried the company through both ballets with a deliberate strength to her fairy figure.

The curtain opening on Serenade’s start is no less than iconic: every ballerina knows the weight of this first scene, a painting of seventeen women in baby blue tulle. Standing still for these few seconds can be the most challenging part of the ballet, especially knowing the technical requirements ahead. The dancers of Los Angeles Ballet were fidgety, and understandably so: artistic director Colleen Neary (a direct descendant of the Balanchine lineage, one of Mr. B’s own dancers) staged the ballet herself, and high pressure was no surprise. But within the constraints of the stage at Royce Hall, they couldn’t quite escape their nerves. The ballet, which expects controlled abandon and a whirlwind-like energy, becomes much more difficult in a cramped space. Each dancer’s range of motion dissipated, and energy extended no further than their fingertips. Spontaneous movements became carefully calculated. Flickering eyelines betrayed lacking confidence.

Enter Bulle, meeting the stage with graceful momentum and navigating a sea of young dancers. She knew exactly where each step would take her, but danced as though she was dancing the choreography for the first time. An embodied joy and gracious port de bras made her captivating, and she exited the stage just as quickly as she entered, bourrees quick and lively.

Eris Nezha supported her well in the waltz but didn’t have much of his own to add. Supporting soloists Jasmine Perry and Petra Conti flickered in and out of artistry but seemed afraid of the floor, dancing without the grounded musicality of the original New York City Ballet cast. This wasn’t the City Ballet Serenade—then again, given recent events, we shouldn’t be aiming to imitate.

In the second half of the evening, artistic director Thordal Christensen’s restaging of Bournonville’s La Sylphide began lively, with scenery (Sören Frandsen) and costumes (Henrik Bloch) as good as any. Conti as the sylph greeted Tigran Sargsyan’s James at the fireplace, but her fairy figure was a bit frailer and flatter: she acted mostly with her shoulders and her movements were stifled, suppressed. Though her stunning facility and long lines helped pas de deux choreography tremendously, the dancing in between was tired, disjointed.

Conti wasn’t the only dancer whose jumps didn’t satisfy. The standard of ballon for a Bournonville company is far from that of a Balanchine cohort. While Balanchine traditionally allowed heels off the floor and choreographed quick petit allegro with sudden directional changes, Bournonville dancers train with ankle weights and are known for their elevation. Perhaps the disconnect here was between directors and dancers: Neary and Christensen both spent time at Royal Danish Ballet, where Bournonville’s influences are strong and his presence as its director 1828-1879 still permeates the company. It follows, then, that the only dancer whose ballon truly impressed was soloist Magnus Christoffersen, who trained at the Royal Danish before moving to Los Angeles. Christoffersen made an impressive Gurn, animated enough to deliver the comedic side of the role and strong enough to execute the short variations. Sargsyan fit the job description for James, but with proficiency rather than excellence. Chelsea Paige Johnston as Effy performed with the right youthful enthusiasm, but landed just short during her big acting scene, abandoned moments before her wedding at the end of the first act.

The second act, featuring an emphatic Neary as witch Madge, brought the dancers to new scenery. Bulle took her place onstage as first sylph with certainty. While her steps were marked by the same precision, her sylph was more reserved, more muted than her Balanchine persona. Her movements were still clear, well-transitioned and purposeful, though perhaps without the conviction she brought to Serenade. The rest of the dancers followed suit, but a specific romantic quality was missing from the staging. Without the forward tilt in the torso to accentuate their wings, it was unclear just how important wings were to the sylph: until Conti lost them in her death scene.

Conti’s execution of the sylph’s death was haunting, undoubtedly the most convincing aspect of her performance. Her fragility lent itself well to the wingless sylph’s loss of flight, and her facial acting reached her body with a pitiful trembling. Her pain was enough to incriminate James completely, if any sympathy was left after Act I. The sylphs carried her offstage before her ascent behind the scrim, as James watched in despair and the curtain fell.

Los Angeles Ballet’s Sylphide and Serenade wandered in and out of flight, with moments of lovely spontaneity among a somewhat strained cast of dancers.

The program will run once more at the Alex Theatre next Saturday, March 16 at 7:30 p.m. Purchase tickets here.

For more information about the Los Angeles Ballet, click here.

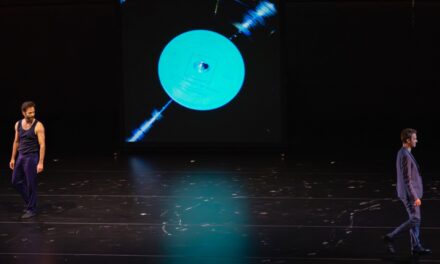

Featured image: Serenade – Petra Conti with Los Angeles Ballet ensemble – Photo by Reed Hutchinson