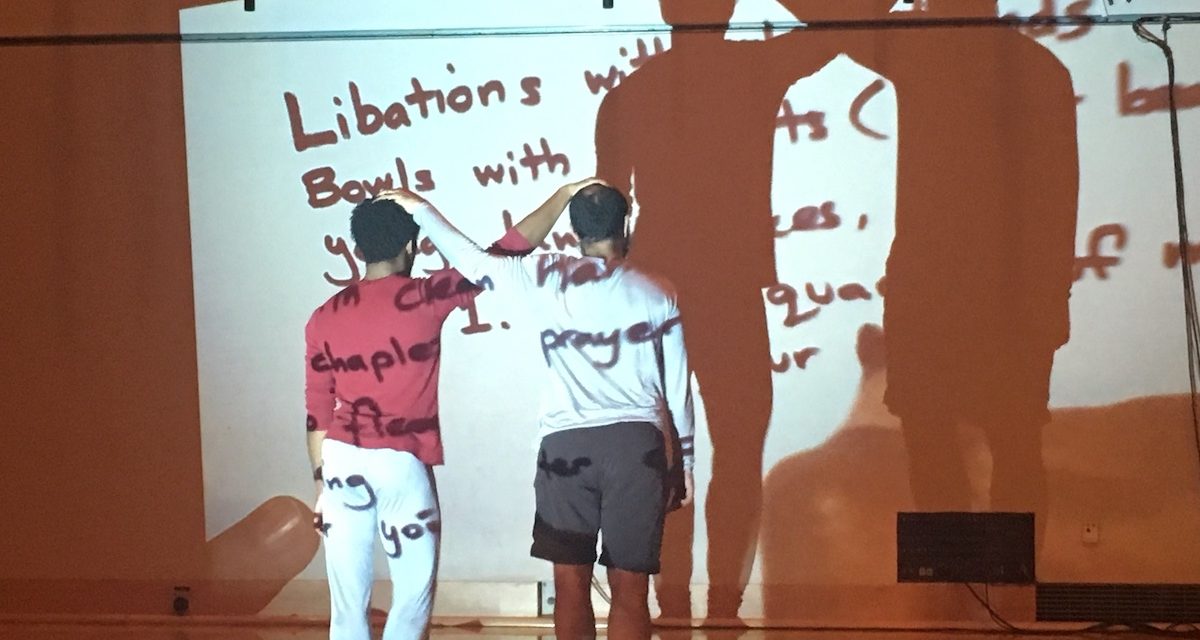

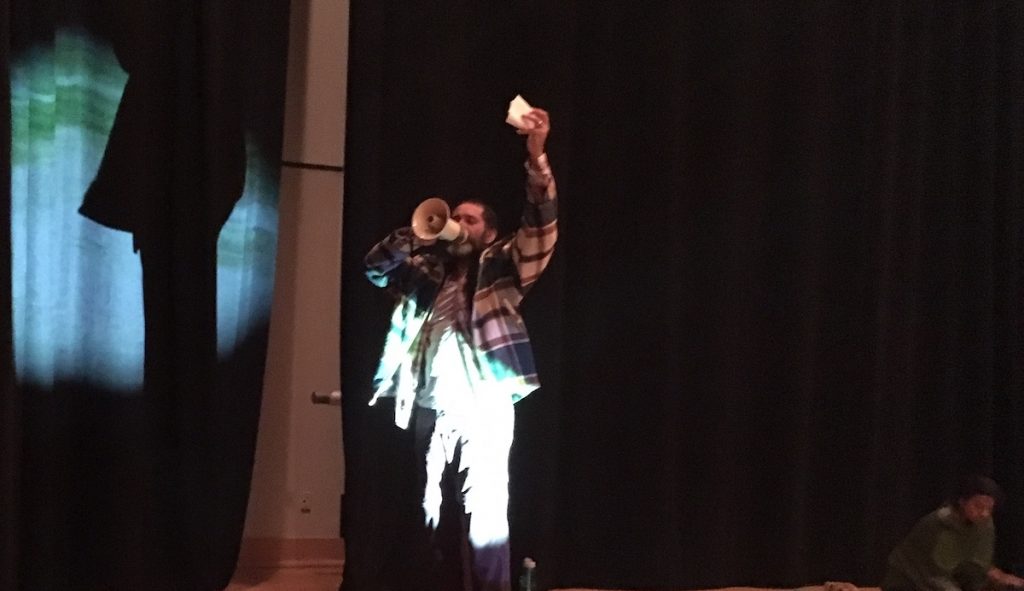

Walking into the darkened rehearsal studio to interview choreographer Lionel Popkin required a bit of navigation with the studio floor strewn with seemingly unrelated objects—a white silk pup tent, lengths of greenery, a stack of books, lanterns, a megaphone, and the other two performers. Barry Brannum is almost invisible, encased in a puffy, purple hooded full-body snow suit, while Meena Murugesan sits among greenery that camouflages the computer she is working on to test some of the projections used in the work.

This is the last week of studio rehearsal, before Popkin and his collaborators move into the Getty Villa for what will be a groundbreaking event, the first fully choreographed dance event presented in the Getty’s 13-year old Villa Theater Lab series.

In separate interviews, Popkin and Ralph Flores, Senior Programming Specialist for Theater and Performing Arts, talked about the upcoming premiere of Popkin’s Oedipus/Antigone Project and the arrival of choreographed performance in the long-running series.

J. Paul Getty’s Malibu replica of an ancient Roman villa opened to the public in 1974 and served as the Getty Museum until the opening of the Getty Center in Brentwood, then was rechristened the Getty Villa with an exclusive focus on antiquities. As the Getty Museum, some limited live performances were offered including a notable version of The Bacchaethat took over the central peristyle garden. After closing for its own facelift, the reopened Villa in 2006 included increased capacity for live performance with an outdoor amphitheater and a separate proscenium theater, a prospect that provoked pushback from the adjacent residents’ association that resulted in various noise and parking restrictions.

Despite those inhibitors, live theater has been a committed focus since the reopening and for those 13 years, Flores has curated all Getty Villa performances. This annually includes a major September theatrical event in the outdoor amphitheater that runs for a month, plus more experimental endeavors in the proscenium theater under the banner Villa Theater Lab, the series welcoming Popkin’s Oedipus/Antigone Project.

Popkin explained that the idea had been incubating with him for about two years.

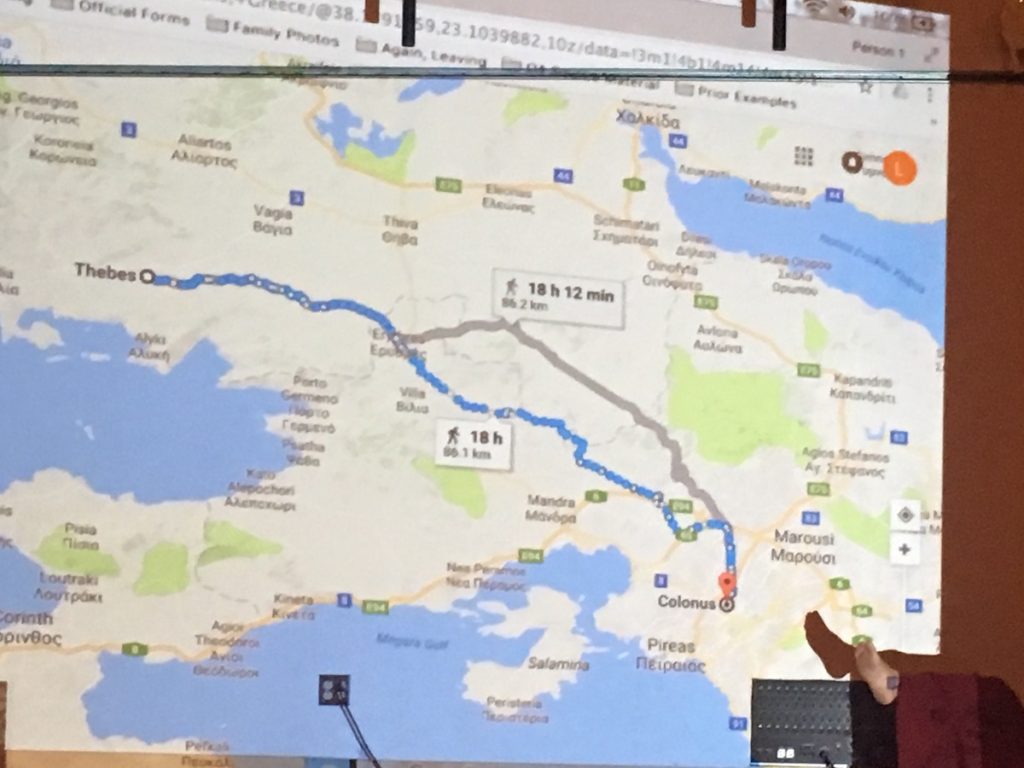

“I kept thinking about Sophocle’s second play, Oedipus at Colonus and how both Oedipus and Antigone change on the journey that starts in Thebes at the end of the first play and extends until their arrival at Colonus at the beginning of the second play. In between is a state where a lot of people are living today and migration is something a lot of people are experiencing.

(Digression on Sophocles’ plays for those who missed Greek Classics 101. For those who know their classics, feel free to skip or send corrections.

Sophocles’ play Oedipus Rex or Oedipus the King recounts how Oedipus’ parents who rule Thebes sent him to die to avoid a prophecy that the child would kill his father and marry his mother, but instead of dying, he was saved and adopted by another king and queen. Learning of the prophecy as an adult, Oedipus mistakenly fears he will kill the only parents he has known, but in trying to run from that fate, kills an unidentified older man who in fact is his real father. Arriving in Thebes, Oedipus solves the Sphinx’ riddle i.e., “what walks on four legs, then two, then three?” with the correct answer, “man as a baby, an adult and when old with a cane” which releases Thebes from the Sphinx’ control and earns Oedipus marriage with the recently widowed queen which makes Oedipus King. That backstory comes out after the play opens with Oedipus already king of Thebes and facing another plague. Told that only finding and punishing the killer of the prior king will end the plague, Oedipus pledges to do so, but uncovers the ugly reality that the unidentified man killed on route was his real father and his current wife with whom he has had two boys and two girls, is his real mother. Learning the truth, the Queen commits suicide. Oedipus finding her, blinds himself and at the end of the play, leaves Thebes in exile with his daughter Antigone as his guide, designating his two sons to share the throne of Thebes in alternating years, which creates its own set of problems which play out in Sophocles’ second and third plays.

In the second play Oedipus at Colonus, the exiled, blind Oedipus and Antigone arrive at Colonus where everyone keeps telling him to go away. The youngest sister arrives with news that the first brother won’t give up the throne and the second brother has an army to back his demand for his turn on the throne. Theseus, the king of Colonus, eventually promises Oedipus sanctuary for the daughters and the play ends with Oedipus’ death.

In Sophocles’ play Antigone, the action returns to Thebes where the uncle has ended up king and declares one dead brother a traitor, forbidding him to be buried. Defying the king, Antigone buries her brother, is caught and ordered to be buried alive in a rock cave to slowly suffocate. The younger sister announces she was complicit and demands to share her sister’s fate, at which the king relents, orders Antigone released only to find she has hung herself to avoid a slower death. End of digression.)

Popkin was drawn to the twenty year gap between the end of Oedipus the King and the beginning of Oedipus at Colonus. “The journey itself took Oedipus and Antigone five years,” Popkin noted, “I was struck that today, that trip takes about 28 minutes. I thought about the length of that journey and the bonding of a family when it is just your family and the rest of society disappears. I had been talking with the curators at the Getty over time as the idea formed and as I worked, it took shape as an examination of being forced to flee a despotic land as well as the mutual reliance and interdependence of the two named characters during their displacement and journey.”

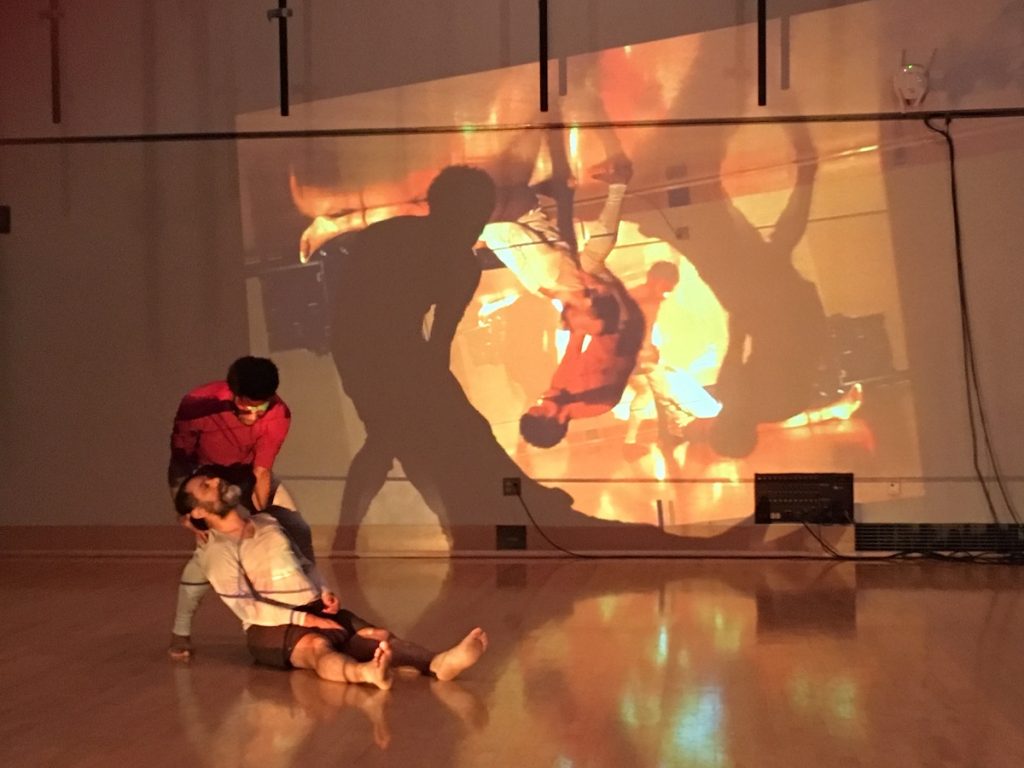

Popkin and Brannum are the principal performers with Murugesan doing double duty, with onstage activity that punctuates the action while also handling the videography.

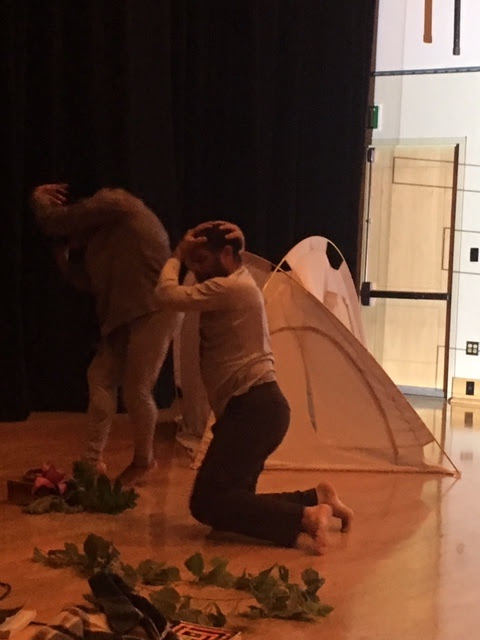

“As is typical of me, no one is a specific character. We trade off,” Popkin explains, “Sometimes Barry is Oedipus and sometimes I am. The same with Antigone. There is character shifting as the characters evolve.”

“There’s a lot of talk about Antigone in the last play as a rebel against the state, but I’m thinking about what took place earlier and how that rebellion was cultivated, perhaps something that evolved over that trip,” Popkin continues, “In some respects Oedipus and Antigone almost crisscross. She starts very young, she grows. He starts as a desperate outcast and over the trip comes to terms with some things about his fate before their arrival at Colonus.”

Activity in the studio shifts into a rehearsal mode as Popkin crawls into the white tent while Brannum, garbed in that purple snow suit, begins reciting directions and Murugesan starts the projections. Over the next hour, the dancers evoke travelers, consolers, searchers armed with lanterns as that white silk tent gyrates and moves, shifting the focus and the action to different stage quadrants suggesting different stops on the journey. Murugesan maneuvers to different parts of the stage while projections shift from Google maps showing the route from Thebes to Colunus, to Mapquest driving instructions, some of which are verbalized. Projected paperwork or applications are written up and the journey continues while projections of the present road to Colonus with cars speeding along the route become a backdrop to the dancers. Along the way, that purple snow suit is shed and shared among the performers.

The run-through is interrupted only twice to go over a tricky section of flailing arms and to adjust the silk tent when a support rod causes an unscheduled collapse. Afterwards, Popkin reviews a section where a soundscape needs to extend a bit longer to support some activity.” Watching the run through and listening to him describe the performers and collaborators, Popkin sounds like a chef who draws on both classic training and contemporary techniques, comfortable that he knows how to maintain the various elements in an equilibrium.

“It is about determining what I am trying to convey at a certain moment and which element to use. There is some text, and overall the text and score are pretty set. Once in the theater, there will always be adjustments when you see what the other elements can do, lighting in particular is an element that I wait for the theater to fine tune.”

Popkin and his collaborators will have two weeks at the Getty Villa theater to rehearse and fine-tune the technical elements. Flores regards that extended rehearsal time as a critical component of the Theater Lab series effort to develop new work for initial performance.

“When the Villa reopened 13 years ago, we started with staged readings,” Flores explained, “but we wanted to do something more substantive and the Theater Lab fills a middle space between staged readings and full performance that funders had pulled away from.”

Barry Brannum, Lionel Popkin (on floor) in rehearsal for “Oedipus/Antigone Project” – Photo by A.L. Haskins

In filling that funding gap, Flores noted that the Getty is very selective in choosing artists interested in exploring the classics and does not accept unsolicited proposals. Over the years he has been found more companies interested in exploring the ancient classics. “They are often not recreating the actual text, but their efforts are rooted in the idea of the play whatever choices are made on how to present or contextualize.”

While some prior text-based and experimental theater works have incorporated movement elements, Flores emphasized the significance of Popkin’s work as the Theater Lab series’ first fully choreographed production.

“Dance is such a different language than text. Lionel explores pending issues about people who have to leave to go somewhere else, people who are exiled from their country and have to find somewhere else to live. He cleverly ties elements from the classics to the situation today.”

Flores is particularly interested in the feedback from the Saturday matinee talk-back session that is a regular feature. “That audience response provides the artists with valuable information about what works, what doesn’t, what isn’t clear, what might be overstated, information that can be used for polishing what will become the finished production. The Saturday matinee talk back is really a wonderful and necessary process to inform artists on whether and how to proceed.” He notes that the Theater Lab track record has had an admirable 65% of presented works go on to fully staged productions both locally and nationally.

An extra benefit of the live performances is the ability to tie performances to the antiquities on view at the Villa. The recent performance of Four Larks’ Katabasis was specifically scheduled to coincide with an exhibition of funerary from Southern Italy and Greece. The galleries are not open for the evening shows, but matinee audiences can view the artwork. Artwork focused on Oedipus is limited but Gallery 209 includes a relief the Sphinx whose riddle gets solved .

Two major artworks on view relate to the next Theater Lab event, the Trojan War. In Gallery 213 an impressive sarcophagus has three episodes depicting Achilles’ life and in Gallery 104, the Judgment of Paris shows the young prince about to make his selection among the three deities that is the seed of the conflict.

Oedipus/Antigone Project at the Getty Villa, 17985 Pacific Coast Hwy., Malibu; Fri., March 8, 7:30 p.m., Sat., March 9, 3 & 7:30 p.m., Sun., March 10, 3 p.m., $7, all tickets are advance purchase.. 310-440-7300, http://www.getty.edu/360.

Featured image: Lionel Popkin, Barry Brannum in rehearal for Oedipus/Antigone Project – Photo by A. L. Haskins