Is there anyone in the dance world not aware of Lara Spencer’s ill conceived and rather gross bullying of six year old Prince George for his love of ballet classes, the resulting rally of the dance community in support of male dancers and the backlash to that; even worse bullying of male dancers by FOX and Friends? Fueled by social media posts, it all took the dance community and popular culture by storm. “They” struck and we struck back, with pride and love and thousands of gorgeous dance photos of stunning men flying through the air. Three of our best dancers met with Ms. Spencer and organized a giant class which took place in Times Square demonstrating the beauty, skill, dedication and compassion that dancers embody. We showed the world that we can be a united force in love for and with our male identifying dancers. Is there really more to unravel in the discussion of the validity of dance as a career for men, the multi layers of masculinity in the dance world and the toxic culture that bullying creates both in the dance world and community at large? I sincerely believe that there is. I still have questions and an underlying sense of unease. I would like to explore how the environment around gender, both in and outside of the studio, affects dancers as they move through performing and into positions of power and influence, and how all of that influences the art and its place in society at large.

First, we have substantial research on how bullying affects boys in dance, particularly ballet, as they go through their adolescence and early career. It is hard and painful and intersects with their sexuality and adolescence in ways that can create lasting personal damage. It is heartbreaking and frankly awful. Yet, the personal tragedies do not tell the entire story. Much of the bullying of boys is perpetrated by those outside of the industry. There is a counter narrative, where boys are elevated within their dance schools and studios. Most boys get scholarships simply for being male. They are nurtured in ways that girls are not, as performers and as future leaders. I am interested in how these conflicting and painful dynamics manifest in the industry as these dancers mature; into performers, choreographers, teachers and artistic directors. For those boys who stay in the industry and forge careers, how does that early (and many times continuing) bullying affect them as the power balance shifts. How do these bullied boys, who fought stigma and adversity to become professional dancers, treat others?

A second impression struck me as this episode played out. When validating the careers of men dancing, we showed hyper masculine, extremely muscular, stereo-typically male dancers. The common argument that football players and hockey players take dance was set out over and over. The tired trope of getting to lift girls all day long appeared. Ballet and modern dance are clearly gendered. Is that due to inner or outer pressures? I want to look at the continuum of sexuality within the dance world. Does dance have to be hyper masculine for it to be acceptable? Humans exist on a spectrum, therefore so do dancers. How do those who are not on one end of the gender spectrum fit into the dance community? Where is the acceptance expanding and how can that be accelerated? Do dancers and choreographers have to take into account the outer world once again in making this transition happen faster, or can we actually be leaders. What do those on the outer edges have to teach the mainstream?

Finally, the gender imbalance in the power structure of dance is incontrovertible. While women and girls make up a large percentage of those in dance schools, the percentage of women leading companies in classical ballet is minute. The ratio of male to female choreographers is 80/20. How is that power shift to men influenced by the difference in acceptability of dance both as a course of study and as a career choice? Is there something in having to overcome such adversity that makes these men leaders? Alternatively, does the extra attention and othering within the dance world that acts as a counterbalance to the bullying lead to this imbalance? Following that line of questioning, is the success of a company also determined by the gender of who leads it? For there is a second side to this treatment. Women, who are generally not attacked outside of the studio, are treated differently within it. Rather than nurtured and set up as something special, they are often bullied by teachers and artistic directors in an effort to break them down, so that they do not believe that they are special or have anything to offer. Therefore, how do women fare as leaders? Do they have to act like men to succeed? The examples of difficulties faced are broad. For example, the reality is that Los Angeles has a thriving dance scene, mostly helmed by women. Rather than celebrate that fact, national press focuses a disproportionate amount of coverage to the few LA companies run by men, while mostly dismissing the scene all together. In what ways does our internalized misogyny and homophobia, combined with our traditional views of gender roles, affect everything from the perception of a company’s importance in the community to the validity of the art as a vital part of society? This affects everything from arts funding to arts education to family life and the ability of artists to earn a living wage.

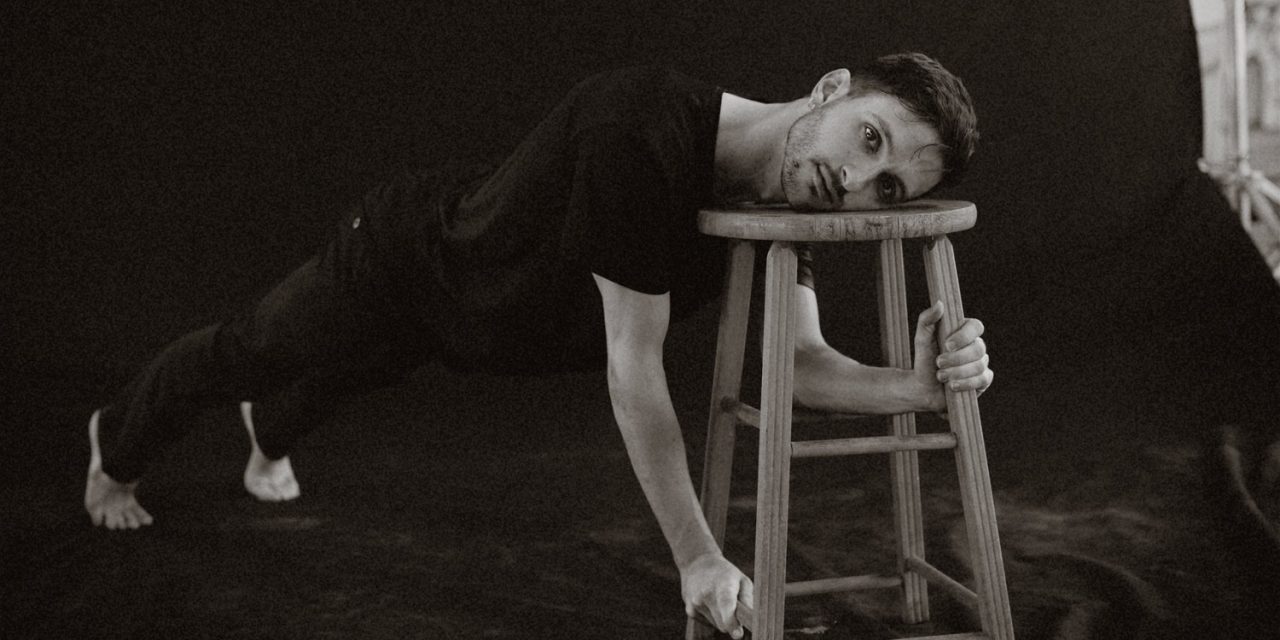

Over a series of two to three articles I will look deeply into the facets of gender dynamics in dance. The articles will include interviews with leading artistic directors and creators including Amy Seiwert; Artistic Director of both the Sacramento Ballet and Amy Seiwert’s Imagery, Scott Gormley, director and producer of the film Danseur, Will McCoy of NoBully.org, Los Angeles Dancer/Choreographer/Dance Educator Andrew Pearson and Anacia Weiskittel, the owner of Degas Dance Studio. We were, as an industry, given a bit of a backhanded gift with this episode. It has focused our attention on these issues and given us an opportunity to look at the causes behind the layers of inequality and frustration in order to enact real change and growth. When all artists are nurtured and supported, the horizon is endless.

Written by Nancy Dobbs Owen for LA Dance Magazine, October 25, 2019

Featured image: Andrew Pearson – Photo by Jerry Sandoval