When I first decided that I wanted to write about the reactions I observed regarding the Prince George bullying incident, I thought it would take me a couple of weeks to look at some research, talk to a few people in the industry and come up with a clear and cogent summary of the problems and perhaps a list of solutions. I wrote the introductory article, posted it and planned to post the second and third over the next few weeks. That was intensely naive. The problems of bullying, homophobia, misogyny, and gender (mis)representation are multilayered, intertwined, serious and intensely harmful. The erasure of talent and ambition, the lack of empathy and inclusion, and the often soul crushing meanness that permeates the dance world is illustrated in hundreds of single spaced links, was choked out during long, tearful conversations, and documented in the pages and pages of detailed and vulnerable answers to the simple questions that I posed. Honestly, if it was all bad, maybe it would have been easier to write, but for every heartbreaking, soul crushing anecdote or relayed experience, there was also a story of dance as the source of salvation, of found family, and of overwhelming love. I plan, over the course of these next two articles, to explore this dichotomy of dark and light all along the spectrum, opening up discussion within and outside of the dance community, hopefully leading to increased understanding, inclusivity, and exploration.

In order to make sense of this immense topic and to honor all of the input from dancers and dance leaders across the country, the two articles will be divided in the following manner. This first one will address bullying and misogyny, both in and out of the studio. How do the patterns of bullying, in all of its permutations, affect and shape dancers as they progress from student life and ascend into new roles as directors, teachers and choreographers? The second article will address gender representation in dance, both how dancers who don’t fit into the binary have been quashed and how the dance community is finally expanding and starting to include all voices and stories, both in and out of the mainstream companies.

A caveat: There are generalizations throughout. Obviously not all boys are treated the same, nor are all girls and those students that identify as non-binary have their own unique experiences, which will be addressed more fully in the upcoming article.

I want to address one additional issue before diving into the substance of these articles. Race is inexorably linked to many of the issues that I have taken on with this series. The intersectionality of race with homophobia, misogyny, representation and power in dance is not a side note, it is an entire chapter in this book. In all honesty, it warrants several books of its own. I would not presume to lump the issues that dancers of color face with those here. However, I will not ignore it and when I have stories that overlap and intersect, race will be part of the discussion. I am also focusing on Western dance forms; mainly ballet and modern within the traditional company setting.

verb: bully; seek to harm, intimidate, or coerce (someone perceived as vulnerable).

“Someone perceived as vulnerable.” Who is more vulnerable than a child unsure of their sexuality, stepping away from socially normative behavior and activities? According to studies, between 1 and 4 and 1 and 3 students is bullied, with most bullying occurring in middle school.

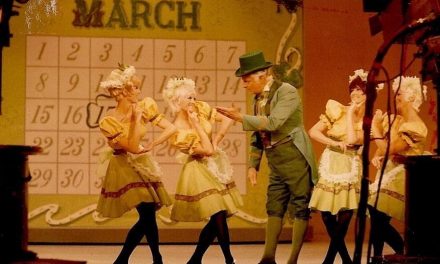

Isabella Velasquez, Anthony Cannerella and Bobby Briscoe in Sacramento Ballet’s “The Nutcracker” – Photo: Chris Hardy

Bullying in dance takes two distinct forms; the bullying of male identifying dancers outside of the studio by their non dancing peers and the bullying, mostly of females, but also of those who fall outside of traditional gender norms, within the walls of the dance studio. This latter form of bullying includes both peer bullying and bullying treatment by teachers, choreographers, and directors and can on occasion be perpetrated by members of the press. It is important to look at the very different ways that bullying manifests in dance, as the ramifications are long lasting and create very different character traits in those who remain in the industry. Many others are simply driven away. This series will focus on those that stay; how does this early experience with bullying (as victim, perpetrator or witness) create specific character and leadership characteristics and traits? Do the effects of bullying affect and influence gender equality and leadership as dancers advance within the community?

Gender study in regard to dance is not new. Countless books and graduate research studies have been written on the subject. What is new and different is the discussion of dance and bullying, of gender equality, and of equality and representation in the mainstream. The connection between how children are bullied and what kind of leaders they become is worth exploring. What creates the dynamics that are played out in studios across the country? This is where the incident with Good Morning America and Prince George comes back. It opens up a discussion. Kathleen McGuire Gaines, an outspoken dancer’s mental health advocate and founder of Minding the Gap, says, “I think the situation with Prince George was an important moment for dance. It was cathartic to see the dance world, a space that is so competitive, unify in support of one another. But I think it also serves as an important reminder of what many male dancers have gone through by the time they reach the sanctuary of a pre-professional program or a company. I say “sanctuary” because dance is a space that is led by men, and where men are considered more valuable than women.”

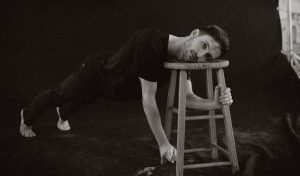

In contrast to the one in four children bullied in the general population, studies show that nearly 96 percent of all boys who dance have faced verbal and/or physical assaults from their peers. Additionally, data compiled by Doug Risner, a professor of dance at Wayne State University in Detroit, shows that only 32 percent of male dancers have fathers who support their desire to dance. This is formidable. Choosing to dance can literally rip a person from their family. The first question to look at is why? Why are boys who dance bullied? Are they bullied for dancing or for their perceived sexual orientation? I interviewed Andrew Pearson, a Los Angeles based dancer and choreographer about his experiences. His answer in regard to this is illuminating; “If you mean bullying based on gender/sexuality – i.e. being bullied because I’m a boy who dances – that happened mostly at school. Never in the studio, never in the neighborhood or with my closer friends.” Pearson didn’t even see the question in regard to dance alone, because bullying in dance, at least among boys, is inexorably linked to perceived sexuality. Boys are not bullied for the ACT of dancing, but because of the belief that dancing is only done by those who are gay, queer, or do not fit the mold of traditional masculinity. The power of this bullying is immense and pervasive. According to Will McCoy, the founder of NoBully, “Bullying is becoming more multi-dimensional than ever. With the onset of the digital environment and the connected world that students are growing up in, the worlds they experience are less separate than ever. That is to say, they are always online, and it bleeds into their school experience. We have found that bullying in the traditional sense (physical, verbal, social) is still pervasive in schools, with 1 in 3 students reporting having experienced bullying in their school lives. Layered on top of that, cyber bullying takes place regularly, and the issues that arise from that experience often ripple into the social situations experienced at schools.” There do seem to be geographic and cultural differences in the amount and type of bullying that boys who dance experience. I informally surveyed my students at both private studios and at AMDA College of the Performing Arts. None of the boys who grew up in Los Angeles or other major coastal cities had been bullied for dance by their peers. All of my students from the Midwest and south had been bullied. Pearson spoke about environment briefly as well. “ I grew up near San Francisco and have always been in California. However, I will say that Orange County, and especially Irvine, is one of the more conservative locations in the state. This may have contributed to me staying closeted through most of college. Even in the dance and theater departments, the gay faculty were very discrete and quiet about their personal lives. It gave a message that being out was inappropriate. So, I don’t know if it’s geography specific, but I do think environment plays a role.”

Scott Gormley was inspired to create a documentary film, Danseur, after his own son was bullied when dancing. The film follows several male dancers at various points in their careers but stops before any of them become leaders in the industry. I highly recommend watching the film. I was lucky enough to see a screening at The San Francisco International Dance Film Festival and it is wonderful, full of heart wrenching stories, obstacles overcome, and beautiful dancing. Harper Waters, a soloist with the Houston Ballet and James Whiteside, a principal with The American Ballet Theatre, stand out for their incredibly vulnerable stories and for the steps that they have taken to fight bullying and stereotypes in dance. I will spend more time on their crusades in the next article. The film however stops before any of the dancers profiled ascend to the level of leadership. Why? I think it is valuable to study how the power dynamic shifts within the studio. This brings us back to the Prince George incident. Gaines continued, “I think it is important that we as dancers witnessed the spectacle of a small boy being publicly bullied for being a dancer. It was an important reminder. When we (female identifying dancers) arrive in the dance studio with these men we have often not witnessed first-hand what they went through to get there. And while we as women were celebrated and encouraged for our love of dance as children (outside of the studio), some of these men have literally lost relationships with family members.”

So, what does happen when boys do get to the studio? For the most part, dance and the studio walls that contain it becomes a sanctuary. The reality is that boys are in short supply in almost any dance studio. Gaines referred to the phenomena as “…the golden dance belt, meaning that men are treated differently simply because dance needs them…” There are numerous scholarship opportunities for boys who want to study dance. Many schools actively recruit them. Anacia Weiskittel, the owner and artistic director of Degas Dance Studio in Encino, California told me about the program that she ran for several years, with which she hoped to address several of the problems that exist for boys in ballet and dance. “For about five years I created a boys full tuition scholarship program in order to help change the culture of boys that danced. I wanted the boys to have a group of peers so that they could learn and grow within this experience. Students in the program didn’t need any prior dance experience and it wasn’t based on potential; only upon pure passion and desire. The only requirements were good behavior, work ethic, a desire to learn, and a minimum of 10 hours a week in all styles (including ballet, jazz, contemporary, hip hop, acro, stretch and conditioning) in addition to performing as members of our team.” She emphasized the importance of the performance element. “If I was going to invest financially in them I needed them to take the commitment seriously and invest in the time. I also felt that the more they were a part of the performances, the more Dads would be in the audiences and would think it was cool, and hopefully break some preconceived stereotypes. Typically, parents put their daughters in dance but they don’t usually consider it for their boys until they are much older and they ask for it themselves. This puts most boys behind for their age (starting at twelve to fourteen years old instead of eight or nine), but they do usually advance quickly. Unfortunately, due to financial reasons and high overhead, I was unable to maintain the nearly $50,000 program. I was pleasantly surprised that even without the scholarship we have maintained the same number of boys dancing seriously in our program.” Perhaps other schools can learn from her experience and remove gender requirements from their scholarship programs. Large classical company schools all have scholarships dedicated to male dancers. For a few examples, you can check out Princeton Ballet, Metropolitan Ballet, and The Rock School’s Program for Young Boys. However, even with the special treatment within the studios, choosing to dance can be isolating and depressing if boys do not have outside support, particularly if they are the only boy in their program. In order to combat those negative feelings and situations, several conventions and schools that focus on nurturing boys in dance have been founded over the last several years. Programs at American Ballet Theatre and The Male Dancer Conference were created to support boys and to create more of a community for male dancers who may feel outnumbered in school and training situations.

For girls (and once again, those dancers who are non-gender conforming) bullying inside the studio can be an issue. Instead of being targeted for one’s perceived sexuality by strangers, parents, and schoolmates, children are subjected to bullying among peers due to favoritism, casting and pettiness. Teachers need to address and stop that from happening, and most do. Once again, Anacia Weiskittel: “In my experience, most if not all of the bullying for boys happens at school or outside and the studio is really a safe haven of friends and support. Many of them won’t tell their school friends they even dance but I am finding that the culture is changing and my younger students now entering junior high school are receiving less criticism, judgments and more support about whoever they want to be. In addition, it helps to have other boys in the [dance] community.” She continues, “Girls are a little trickier and bullying is more subtle and socially excluding. It usually has nothing to do with dance specifically.” Addressing this type of bullying directly stops it from spreading. “At the studio we have several ways of dealing with bullying. First I set strict guidelines that I won’t tolerate it and have kicked out many great dancers or parents that cause drama. In my opinion it is imperative to being open and able to try new things and explore movement for it to be a safe space. We start young with class etiquette, body language and don’t allow simple things like whispering. We talk about us all wanting to keep this a safe and kind space. In addition, when situations occur between students I set up meetings with me and or our peer counselors which are our Junior and Senior High School students that will help mediate conversations and help the students work things out.” Weiskittel emphasizes a hands-on approach and has created a very open and creative space where all dancers are treated with respect.

For girls (and once again, those dancers who are non-gender conforming) bullying inside the studio can be an issue. Instead of being targeted for one’s perceived sexuality by strangers, parents, and schoolmates, children are subjected to bullying among peers due to favoritism, casting and pettiness. Teachers need to address and stop that from happening, and most do. Once again, Anacia Weiskittel: “In my experience, most if not all of the bullying for boys happens at school or outside and the studio is really a safe haven of friends and support. Many of them won’t tell their school friends they even dance but I am finding that the culture is changing and my younger students now entering junior high school are receiving less criticism, judgments and more support about whoever they want to be. In addition, it helps to have other boys in the [dance] community.” She continues, “Girls are a little trickier and bullying is more subtle and socially excluding. It usually has nothing to do with dance specifically.” Addressing this type of bullying directly stops it from spreading. “At the studio we have several ways of dealing with bullying. First I set strict guidelines that I won’t tolerate it and have kicked out many great dancers or parents that cause drama. In my opinion it is imperative to being open and able to try new things and explore movement for it to be a safe space. We start young with class etiquette, body language and don’t allow simple things like whispering. We talk about us all wanting to keep this a safe and kind space. In addition, when situations occur between students I set up meetings with me and or our peer counselors which are our Junior and Senior High School students that will help mediate conversations and help the students work things out.” Weiskittel emphasizes a hands-on approach and has created a very open and creative space where all dancers are treated with respect.

Shannon Chain – Photo: Weiferd Watts

As demonstrated by the atmosphere at Degas Dance Studio, bullying among students (and occasionally parents) can be dealt with and minimized by a serious hand on approach. It is the bullying incorporated into dance training that has long lasting effects, affecting both who ascends to leadership positions and the manner in which they lead. Boys are often given every advantage to experiment and explore while girls are frequently trained to be submissive, quiet and to fit in. Leaders are not submissive, quiet, nor do they fit in, so the compensation for the ways that boys are treated outside of the studio, combined with the supply and demand of male versus female dancers within the confines of the studio creates conditions where males advance and stay in leadership positions and women follow directions. This continues into professional life. Kate Crews Linsley, the Academy Principal of Nashville Ballet and a former dancer with Ballet West says, “ I will be blunt here. Men more than often get the job simply because of their gender and are often not as talented and/or do not have the same work ethic as you and your female counterparts. It’s the old stereotype. Women make up the corps de ballet, but companies kill themselves to hire men. Women are expected to have a certain (sometimes submissive) behavior in the studio as the “ballerinas” and men can use their voice more freely and expressively. These are unwritten norms, but part of the structure of studio life. I have seen directors blatantly speak to female dancers and artistic staff differently due to gender.” Most dancers and former dancers that I spoke to would not give names nor go on the record, but the list of abuses during training and into professional life is as follows: yelling, screaming, expletives, double standards (for men and women, and also sometimes used racially) dancers being put in uncomfortable situations, both professionally and sexually by directors or choreographers, directors not having their backs, and endless body shaming. Much of this is attributed to “tough love” or “tradition.” Andrew Pearson said that “the way dance is taught can often be riddled with bullying.” All dancers experience some of this, but women experience it more, and because of the power imbalance, the consequences are greater. It is so ingrained that many teachers do not see the inequity nor the inhumanity in it. For example, Shannon Chain, a stunning former dancer with American Ballet Theatre and the Zurich Ballet, who is now a doctor and mother of three, was taking class from a well-known teacher in the SF Bay Area just this fall. She recounted the following on her Facebook Page: “Nothing like an old ballet teacher to make you feel like complete crap. ‘We are not defined by our fat’ as he grabs my love handles, then…’You don’t need to be beautiful anymore, you used to be’.” The culture of bullying, especially of men to women, is so powerful that this teacher thought nothing of both inappropriately touching and belittling a highly accomplished women because that is the way it has always been done.

“Don’t think dear, do.” George Balanchine.

Isabella Velasquez and Eliot Maroney Sutton in Sacamento Ballet’s “The Nutcracker” – Photo: Chris Hardy

This is a good place to insert a short history lesson about women in ballet. Ballet originated in the courts of Catherine De Medici in Italy in the fifteenth century. It was danced by men. Women did not start to become integral to the art form until the early 1800s with the invention of the pointe shoe and the start of the Romantic Era. The balance of power began to shift onstage, with male dancers losing the respect of society, but the power remained with them behind the scenes. The ideal of the Degas ballerina encased in tulle, delicately tying a pointe shoes disguises the fact that the men lurking at the edges of those paintings were buying sexual favors from the dancers and though those dancers were artists, they were also basically prostitutes. These men could make or break the careers of any ballerina, lifting her from an impoverished life into one of opulence and stability. Societal views shifted again as the Russians elevated the art form in the latter half of the 19th century, leading to the modern era. Though women did play some leadership roles in dance moving into the modern era of dance particularly Ninette de Valois, who founded the Royal Ballet, men led and continue to lead most ballet companies. The percentage of pieces choreographed by men is formidable. Lest we think this is an American problem, this article from last year focuses on the same issues in Canada and England. While many of the breakthroughs in modern dance came from a generation of women fighting these gender roles and the confines of classical ballet, today modern dance is only slightly less male dominated than ballet.

So, what are the solutions? How do we honor all of our dancers and their individual hardships while shifting the gender balance in leadership to reflect the population, both in and out of the dance world? In addition to Kate Crews Linsley and Anacia Weiskittel, I interviewed three amazing women who are all working in or towards leadership roles in ballet: Amy Seiwert is Artistic Director of The Sacramento Ballet as well as the founder and Artistic Director of her own company, Amy Seiwert’s Imagery. Her Nutcracker is the only full-length ballet choreographed by a woman this season among the top fifty companies in the United States based on research by the Dance Data Project who’s “theory of change is that once the public, dance critics, and foundations know the numbers, they won’t be able to hide any more.” Stella Abrera-Radetsky is a principal dancer with American Ballet theater and in January is stepping into a new role as Artistic Director of Kaatsbaan, the Hudson Valley’s cultural park for dance and an incubator for the growth, advancement and preservation of professional dance. Nicole Haskins is a ballet choreographer and dance educator who has had pieces commissioned by Richmond Ballet, Smuin Contemporary Ballet and Oregon Ballet Theatre among others.

The first step is to change the ingrained patterns of abuse in dance training. For women especially, we have to find our literal voices. Haskins calls it “…the power of the ask. Men are not afraid of asking… It is not bizarre or overstepping [to ask for an opportunity].” While we do this, we have to honor ourselves and not turn into what we have experienced. How do we break the cycle of women needing to act like men to be leaders? Men who were bullied as children, who may have less empathy and more anger and who were then brought up within a system that degrades women. These men were boys who absorbed the abuse and then, like any abused child, pass it on to the next generation. It takes conscious action to change. Many dancers interviewed (including me) recount that though they had abusive teachers and directors of both sexes, the worst ones were always female. Linsley states, “Interestingly enough, I have found that the harshest critics and most complicated choreographers and coaches I have worked with have been women. I feel that the standard of ballet, the issues with weight, idealism and perfection have come from females that were treated in a certain way and that they understand that these things are how the ballet world works and if they were told these things, so should the dancers that they are now working with. That this behavior of shame is the way that we work in the ballet world and that it should continue based on tradition and standard.” Kathleen Gaines shares similar sentiments, “Sometimes female leaders in dance are the most supportive and gracious figures you will encounter, but all too often the opposite happens as well. There can be a mentality among female leaders that they struggled, they proved themselves, they were abused and minimized, so they must ensure you go through the same. Either because they believe that is how you “make a dancer,” or because they think you should have to prove yourself like they did. The abuse of women by women in dance culture is important. The truth is that there is an issue of generational trauma in dance. Because abusive practices and behaviors were normalized for your teacher, they pass them on without thought. I felt minimized by several male leaders as a dancer, but the most abusive teacher I encountered was a woman, and she is still in a position of power over dance students today.” This struggle to maintain our souls continues as we become leaders ourselves. Kate Crews Linsley states, “It is interesting to continuously feel that in a traditionally female driven art form the closer you get to upper leadership positions the more you need to be a powerhouse and elite to be considered and have staying power at this level. I still feel that if I had similar qualifications to a male counterpart, that the male would be chosen. This could be a result of my past or an old story, but I would like to change that belief system, if not for myself, but for future generations. We should ALL be considered for our worth on our merits, not our gender.” All of this takes a very conscious effort on the part of all industry leaders and future leaders. There has been a trend of women’s’ choreography festivals or seasons dedicated to female and female identifying choreographers. Many leaders that I spoke with cautioned against these festivals or seasons as signs of change. Until women become woven into the everyday fabric of leadership, these festivals are simply band aids with value in the moment, but not as harbingers of change. Haskins reminds us of the history of ballet and of Western Dance. She states, “We need to be more cognizant of where ballet came from…until we address where the problems, and by problems I mean implicit and institutional biases, came from, we won’t be able to really address the gender imbalance. I think we need to examine how we got to the place where women don’t feel comfortable asking for opportunities.” She recommends bias training and for leaders to really “get down in the weeds” to restructure.

So, this is a lot of what not to do and what needs to change. In contrast to that, there are positive actions that can be taken. Each conversation that I had also focused on the power of mentorship. Whether it was one-on-one mentoring or through programs designed to increase one’s creative output, mentorship is key. Building programs that feature it is one concrete step that we can take to actively change the industry . Both Seiwert and Haskins danced and choreographed for Smuin Contemporary American Ballet and were able to create works while still company members, which is rare for women in ballet. Seiwert especially credits Michael Smuin as a choreographic mentor and teacher. Haskins also had seven years with Sacramento Ballet where she was able to participate in their choreographic workshop, which was open to everyone in the company. It allowed more women to participate because it did not take time away from their other training. She spoke eloquently and passionately about the need to “explore without pressure” and her gratitude for these two companies and their “value of the creative process.” These workshops and opportunities counteract yet another aspect of dance bullying that is especially focused on women. Seiwert, “Young women are taught to be “perfect” and that they are a dime a dozen. Young men are put on scholarship and given solos. This is all happening in developmental years, when the part of your brain that processes emotion isn’t connected to the logic part. As a field, we need to seriously change how we are treating young women while still developing strong, technical artists.” Haskins referred to women being required “to put all of their eggs in the performance basket.” In contrast to that all or nothing performance approach, Abrera-Radetsky credits ABT Artistic Director Kevin McKenzie for recognizing a talent for programming and for supporting her passion for “using her dance platform to benefit charity” and for “fostering the mentality to be creative, innovative and to trust her instincts” as she takes the next steps in her career.

Seiwert, Abrera-Radetsky and Weiskittel are all actively working to create similar opportunities for upcoming dancers. At Imagery, Seiwert recently launched Imagery’s Artistic Fellowship. Though the program is for all choreographers, not focused on women, it is definitely a way of passing on the mentoring that she received as a young choreographer. Abrera-Radetsky is creating the very opportunities at Kaatsbaan that Haskins credits with her own choreographic journey; a situation where choreographers have time, space and dancers without the pressure of a commissioned piece. At the student level, Weiskittel has created a wonderful choreography program in her school. She says, “ I try to change this dynamic [of only males being encouraged to make new work] in my studio in a couple of ways. We teach choreography composition and improv flow at a very young age with all genders. Our studio is more inclusive when it comes to ballet in that we treat every student regardless of their (stereotypical facility) for ballet so that everyone is being trained at the highest levels based on their passion and work ethic instead of purely facility. I believe that even if we can’t change the professional ballet industry when it comes to body-types and genetic composition that we can still train some of the next ballet choreographers, directors, teachers and help each student find their personal dance paths in all styles on stage and behind the scenes.”

I want to return to the incident with which I started this article, Lara Spencer’s ill-conceived bullying of Prince George. One of the beautiful outcomes from this ugly episode was the way in which the female dance community rose up in arms to defend, protect and honor our male colleagues, partners and in many cases, students. It was an organic uprising and one that fills me with joy. But, I am still waiting for the reverse to be true, for companies and male leaders and dancers to stand up for the women who teach and dance and have something to say. Kathleen McGuire Gaines completed her statement to me with the following, “I think it is important that we as dancers witnessed the spectacle of a small boy being publicly bullied for being a dancer. It was an important reminder. When we arrive in the dance studio with these men we have often not witnessed first-hand what they went through to get there. And while we as women were celebrated and encouraged for our love of dance as children, some of these men have literally lost relationships with family members for the privilege of “the golden dance belt.” So, we all pay for it. For the love of this artform. We just do it in different ways and at different times. No one gets to skip the toll booth. I think it is important for female dancers to remember this and avoid seething if I were a guy I wouldn’t have to be as good. But equally as important is that men in dance use their privilege within dance spaces to advocate for and protect women who are being belittled and abused before their eyes. ”

Teaser for next article:

Gender representation in Dance: Beyond the Binary: More from Andrew Pearson, Amy Seiwert, Kate Crews Linsley and Anacia Weiskittel, as well as additional conversations with Katy Pyle, the artistic director of Ballez, Sean Dorsey, Los Angeles dancers Annie Grove and Grace Horrocks, and dance educator Courtney Bold.

Written by Nancy Dobbs Owen for LA Dance Chronicle, January 6, 2020.

Featured image: Isabella Velasquez and Anthony Caneralla in Sacramento Ballet’s “The Nutcracker” – Photo: Chris Hardy