I’m going to be honest. I am a fan of Celia Fushille, the Artistic Director of Smuin Contemporary Ballet in San Francisco. A big fan. A longtime fan. I remember standing behind her in professional classes at Dancer’s Stage on Brady Street in San Francisco when I was a star struck teen and she was, at least as far as I could tell, an established star. She seemed perfect. The teachers all loved her. Her technique was impeccable and she was nice. She was such an inspiration and she was kind. Nothing could be more appealing. It appears that not much has changed. She is still a star; she is still kind and I am still a little awestruck.

Ms. Fushille has been the Artistic Director of Smuin Contemporary Ballet since Michael Smuin died unexpectedly in 2007. His eponymous company, founded in 1994 under the name Smuin Ballets/SF then Smuin Ballet, aimed to create a truly American company, infused “with the rhythm, speed, and syncopation of American popular culture.” It is an astonishing feat to take a company founded upon the work and personality of one man and expand it into a dynamic incubator for new choreographers and creative dance problem solving, especially as a Hispanic woman in a field dominated by white men, during an economic downturn. I wanted to explore what combination of hard work, determination, mentorship and fairy dust made it all possible.

Ms. Fushille grew up in El Paso, Texas as the fifth of seven children. She began serious training at age eight (after an aborted attempt at age four) with Katherine Clark, a former dancer with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo. Four years later, she began to work with Ingeborg Heuser, a former dancer at the Berlin Opera Ballet, who was also head of the dance department at University of Texas at El Paso. Ms. Heuser also ran her regional ballet company, Ballet El Paso, out of the UTEP facilities. It was with Ballet El Paso that Ms. Fushille started to really create the foundation for a professional career. “I never had a dream of being a professional ballerina. Somehow, I accepted that I was not in that group of girls that are good enough/lucky enough to make a career of dance. I didn’t consider a professional career as a possibility until I was 15 when I realized I might have the ability.” She started attending San Francisco Ballet School Summer Intensives at the age of thirteen. At the age of sixteen, Oskar Antuñez, who danced with the Royal Danish Ballet, Les Grande Ballet Canadiens, and Harkness Ballet Theater, and served as Ballet El Paso’s ballet master, created her first leading role in a ballet. She says, “He was a real mentor to me at that time.” She moved to San Francisco permanently, after graduating early from high school, at the age of seventeen. She worked with San Francisco Ballet for two and a half years, both as an advanced student and as a company apprentice, traveling and performing with the company. She left for a year and then was invited by Michael Smuin to rejoin for the 1983-84 season, though a knee injury prevented her from continuing.

Michael Smuin was the Co-Artistic Director (with Founder Lew Christensen) of San Francisco Ballet from 1973-1985. This was a period of immense growth for the company. During the Smuin era the company rebounded from a bankruptcy, debuted its own orchestra under the baton of Denis de Coteau, and established Dance in Schools and Communities (DISC) in response to an expressed need for arts instruction in public schools. Smuin’s Romeo and Juliet was the first full length ballet (and the first from a West Coast company) to be shown on the PBS television series, Great Performances: Dance in America. Smuin received an Emmy award for Choreography for the Dance in America national broadcast of A Song for Dead Warriors. He left SFB in 1985 after a political upheaval within the company which led to Helgi Tomasson taking over as artistic director. Over the next nine years, Smuin worked on Broadway. He received Tony nominations for both his choreography and direction of Sophisticated Ladies, which starred Gregory Hines and Judith Jamison. In 1988, he won the Tony for his choreography of Lincoln Center Theater’s revival of Anything Goes. It wasn’t all successful, as he directed and choreographed the big-budget flop Shogun, The Musical in 1990. In addition to stage work, Smuin choreographed for film including the Francis Ford Coppola films Rumble Fish, The Cotton Club and Bram Stoker’s Dracula. Other film credits include A Walk in the Clouds, The Joy Luck Club, The Fantastiks, and Star Wars: Episode VI – Return of the Jedi (Special Edition). He founded his own company in 1994.

During Smuin’s Broadway era, Ms. Fushille moved on with her life as well, creating both family and stability. “After rehabbing my knee, I returned to dancing with smaller Bay Area groups, married and started my family and in 1991 began performing with the San Francisco Opera Ballet. I was working with the Opera in the fall of 1993 when Michael approached me about working with him at his own company. I was the first dancer he hired.”

Ms. Fushille was a company leader from the start. “When Michael asked me to join him at Smuin Ballet, the offer was twofold: to work as a dancer and assist him as ballet master. In 1998 Michael promoted me to associate director.” Her role at the company expanded as the company grew and evolved, especially upon retiring from the stage. “After retiring from performing in August 2006, I intended to focus my energies full time on my role as associate director. By then I was handling the day to day in the studio, making the schedule, staging existing works and giving the artistic report at board meetings. Michael would come in to create new pieces.” She had expected this relationship to continue for years to come. “I used to ask Michael how long he would choreograph and he thought he’d continue until he was 75 or so. I expected another decade assisting him at Smuin Ballet. I was an effective second-in-command for Michael. I was there to support his vision completely.”

Michael Smuin died April 23, 2007. He had a heart attack while teaching company class. “I was not in the studio the day he died. I had taken my daughter to Boston for an open house for admitted students at Tufts University, where she ultimately attended college. I received a call when he collapsed while teaching company class and returned to SF that night.” There was no break. “The day after Michael died the dancers wanted to rehearse. They had been given the opportunity to take a few days off, but they were insistent on coming in to rehearse. We were about 3 weeks away from the opening of our spring season and Michael had just finished his final work, Schubert Scherzo. That week we would dance and then we’d cry, just getting through each hour of every day. “

Smuin dancer Erica Felsch as “The Rose” in Annabelle Lopez Ochoa’s “Requiem for a Rose”, which enjoyed its West Coast premiere with Smuin in fall 2017. (Photo credit: Keith Sutter)

When I asked Ms. Fushille if she aspired to lead a company, the answer was a definite no. “ I never aspired to being artistic director, much less executive director of Smuin Ballet.[…] It’s a very different pressure to be the one in charge, creating the vision and the direction for an organization. This was not a position I sought despite having an example of a female Artistic Director while growing up in El Paso.” Despite not aspiring to the position, she was prepared and already a company leader. Nevertheless, the transition was difficult. “ I’m not going to sugar coat it, the first year after Michael’s death was devastating. If you have lost someone dear to you, someone who is in your life every day, you know what it is like to experience everything in a full calendar year without that person.“ ———“For me personally there was an enormous amount of adjustment as I was dealing with several life stressors at the same time: Michael’s death, my divorce, moving from a home we’d been in for 12 years, dealing with an empty nest, career transition…To handle it all, I put my full energy into running the company. That became my therapy.”

It was difficult for everyone in the company, both dancers and creative teams. “Not only were we all grieving, we were adjusting to a new dynamic. Although the dancers had always seen me in a managerial position, it was an adjustment for them and for me to be the one in charge. The board later brought in a consultant who facilitated some learning and coaching opportunities for me and others in the organization. We also had a company retreat that helped us grow as a team and learn to communicate more effectively. I also shared my plan for moving forward.“ Some of these difficulties worked themselves out naturally as the company gradually shifted. “For the dancers, the biggest change was that no longer was the artistic director the one doing all the choreographing and casting. Dancers had to be ready to be noticed by visiting choreographers, essentially auditioning each time one came in. As the years passed, new dancers joined who had only known me as their artistic director and the transition eased each year.” Ms. Fushille continues; “The adjustment seemed more pronounced in some ways for the production and administrative teams to see and truly accept me as the leader of the organization. I did not profess to know all the answers, but the consultant I mentioned helped us work though some of the issues.” Finally, she brings it back to her mentor; “I’d ask myself, ‘what would Michael do?’ Michael also told me to always trust my gut, and that has also served me well.”

Smuin dancer Erica Felsch as “The Rose” with the Company in Annabelle Lopez Ochoa’s “Requiem for a Rose”, which enjoyed its West Coast premiere with Smuin in fall 2017. (Photo credit: Keith Sutter)

So, how do you take a company created in the image of its founder and move into a new phase? There is no doubt that Michael Smuin made his company in his image. He created over forty ballets for the company drawing from all of his influences; classical ballet, Americana and Broadway. His Christmas Ballet is a perfect distillation of his work: Act One is a Classical (ballet) Christmas, Act Two a Cool (jazz, tap and everything else!) Christmas. The ballet continues in the repertoire today, with new additions by current choreographers each season. His now classic Fly Me To The Moon, incorporates ballet, social dance and tap. The masterpiece Stabat Mater uses classical technique to mourn those lost in the 9/11 terrorist attacks. These dances all showcase his innate theatricality and versatility. Yet, for a company to survive, it cannot simply repeat the same repertoire year after year. Ms. Fushille needed a map forward to take the company past the point maintenance, to let it grow and evolve beyond what Michael Smuin had created. “One month after Michael’s passing I was asked by the board president to prepare my 5-year plan for the company. I was given 4-5 days to prepare this. At that time, I presented my plans about how I thought the company should continue. I knew that if we became a museum company, doing only Michael’s works, Smuin would not survive.”

This evolution took several years, with conscious work by both the artistic and financial leaders of the company. The supporters, for the most part, went along for the ride. Ms. Fushille elaborates; “The decision was conscious to begin introducing the works of other choreographers while maintaining Michael’s legacy. It was not until about 9 years after Michael’s passing that I presented a rep(eratory) program that did not include any Smuin works. There are some fans that are Michael devotees, which I love, and they would like to see more works like Michael’s. Some of them noticed a lack of MS works and commented, but for the most part our supporters came along with me on this choreographic journey.” In any non-profit, the support of your board of directors is essential. “For many years, the board remained unchanged and exceedingly supportive. Many trustees served 10,15, 20 plus years. The board evolved naturally, especially as we moved from a small ‘mom and pop’ operation or start up, to a bona fide Bay Area dance company.” The board has evolved and grown but is still emotionally connected. When moving into their new building at the end of 2019, the first that they owned, Patti Hume, the company’s first board president was quoted saying, “It makes me cry. It’s a dream come true.”

Smuin dancers Terez Dean Orr and Ben Needham-Wood in Amy Seiwert’s “Renaissance”, a world premiere presented in the Company’s spring 2019 program. (Photo credit: Chris Hardy)

Smuin himself also set things in motion for the future. He supported new choreographers, especially women, when many didn’t and don’t. The gender gap in ballet is well established, but young untested choreographers had a place with Smuin Ballet. “Even in his days at SFB, he provided choreographic opportunities for the men and women of the company. Many are still working in the industry today. He did continue this at Smuin, even giving me the opportunity to choreograph, which totally intimidated me. Amy Seiwert had already been choreographing when she came to Smuin, and Michael found her voice to be unique and worthy of encouragement.” Ms. Fushille continued the path that Mr. Smuin started. “When Amy retired from dancing I named her Smuin’s first Choreographer in Residence. In 2008 I implemented Smuin’s Choreography Showcase in order to foster the next generation of dance makers. In some ways it formalized a process begun by Michael. The dancers are given a supportive and creative environment to create works on one another and bring a work from a concept or inspiration, all the way to its production on the stage. The opportunity is open to any dancer and I was quite proud that in March at our last Showcase, more women than men in the company chose to create.”

You cannot interview a ballet company artistic director who identifies as female and not discuss it. Ms. Fushille once again gives Michael Smuin credit for leading the way. “In many ways, Michael was ahead of his time. In the 70’s and 80’s he was trying to create work that pushed the boundaries of ballet. Michael adored his dancers and always appreciated strong women. He always said, ‘if you need to get a job done, give it to a woman’. He felt a woman would get the job done without her ego getting in the way. Michael had the best example of a strong woman in his mother, who was his first advocate.” She reflects upon her own role. “I did not realize until a few years after being named AD that I was in a very select group of women holding this position in the US and in the world. I have reflected on why there are so few women in these roles. The issue is multi-faceted and stems from cultural and societal gender norms. Like we are seeing in business and the board room, women are working to be heard, and to advance professionally. Stereotypes must be broken.” Just like in business family life can also interrupt a woman’s path. “Another factor contributing to the issue of women assuming leadership roles is similar to women is business: the timing and impact of starting a family. It’s becoming more common to see women in ballet return to dancing after starting their families, but in my generation, it was still the exception. It was rare to see a woman having a family and a career.” Finally, the training in ballet does not lend itself to nurturing female leaders. “In the ballet world specifically, girls are not encouraged to stand out, they are taught to be obedient and to fit in. Girls know they are replaceable. Boys in ballet are a rarity, and their spirited or boisterous behavior is quickly forgiven and tolerated since boys are essential. This treatment alone gives boys more confidence to advocate for themselves in ways that girls rarely do. Whether seeking to try their hand at choreography or directing, boys are more apt to seek opportunities since they are less accustomed to rejection.”

Smuin dancers (l-r) Valerie Harmon, Nicole Haskins, Tessa Barbour, and Ben Needham-Wood in Amy Seiwert’s “Renaissance”, a world premiere presented in the Company’s spring 2019 program. (Photo credit: Chris Hardy)

In the time that we started to talk about this article, both the Covid-19 crisis hit and the George Floyd protests exploded across the country. We discussed both and I touch on them here, though each is deserving of a full article. Smuin Contemporary Ballet just moved into its own home, a bright sunny space in San Francisco’s Potrero Hill district. They had to then cancel the Spring season and Ms. Fushille and her board are working within the constantly changing landscape to ensure “there is a company that continues to thrive on the other side of this crisis.” And, of course, like many other companies, the dancers continue to dance.

Ms. Fushille continues, “There are many societal shifts coming for our country and the world. The #MeToo movement and fights for equality, diversity and inclusion are impacting the way we look at every aspect of our world. They are also impacting the way things happen in the ballet world and I believe it’s a good thing. In any line of work, people should be allowed to focus on the work, and not fear any sort of harassment or prejudice.”

This led to my final questions. I asked how Smuin Contemporary Ballet is specifically working to increase diversity and representation of Black and Brown dancers and choreographers, as well as designers and financial backers. Is this something that the board is actively working on moving forward? Ms. Fushille responded immediately and in full;

“I’m glad you mention this. I had an email from SFB on Friday where they reposted a link to a panel discussion on diversity and inclusion I was invited to be a part of 2 years ago.

Last Monday on a Dance USA call with Artistic Directors from across the country, I was the only company Artistic Director that had a statement ready to post on social media expressing our position on recent events, denouncing racism and working to be part of the solution. I read our statement on the call and shared this with some of the companies. It may be the basis of a joint statement from ADs across the country.

We have had these conversations about diversity and inclusion at the board level. This coming season I have two openings for men and one of the men I have hired is African American. As a female, diversity is especially important to me and I hope that Smuin will reflect the communities in which we perform. Next season 29% of my dancers will come from diverse backgrounds. One of my current dancers of color was stunned to receive a message checking in on him following these horrific events. As a non-profit organization, I am not supposed to be political, but these events have nothing to do with politics. They are questions about humanity and equality.

The Smuin Company in Amy Seiwert’s “Renaissance”, a world premiere presented in the Company’s spring 2019 program. (Photo credit: Chris Hardy)

During these turbulent times, everyone needs to be asking themselves these questions.”

Smuin Contemporary Ballet’s Statement:

As an organization of creators, we stand in solidarity with all those who suffer senseless acts of racism in their everyday lives. To be silent is to be compliant. When we see injustices served upon a community that helps to make up our own, we need to take action. Today, in a show of unity with the black community, with those who are mourning the senseless murder of George Floyd, and for the many black lives lost, we take a break from talking about ourselves. Finding justice within our community begins with finding our own accountability. Here at Smuin Ballet we celebrate the members of our community who are facing racism every day. As a company with a platform and a voice, we acknowledge that there is a problem, and we commit to being a part of the solution.

Written by Nancy Dobbs Owen for LADC, June 22, 2020.

There were several updates requested by the author which have been recorded. The last update was made on 6/24/20.

To visit the Smuin Contemporary Ballet website, click HERE.

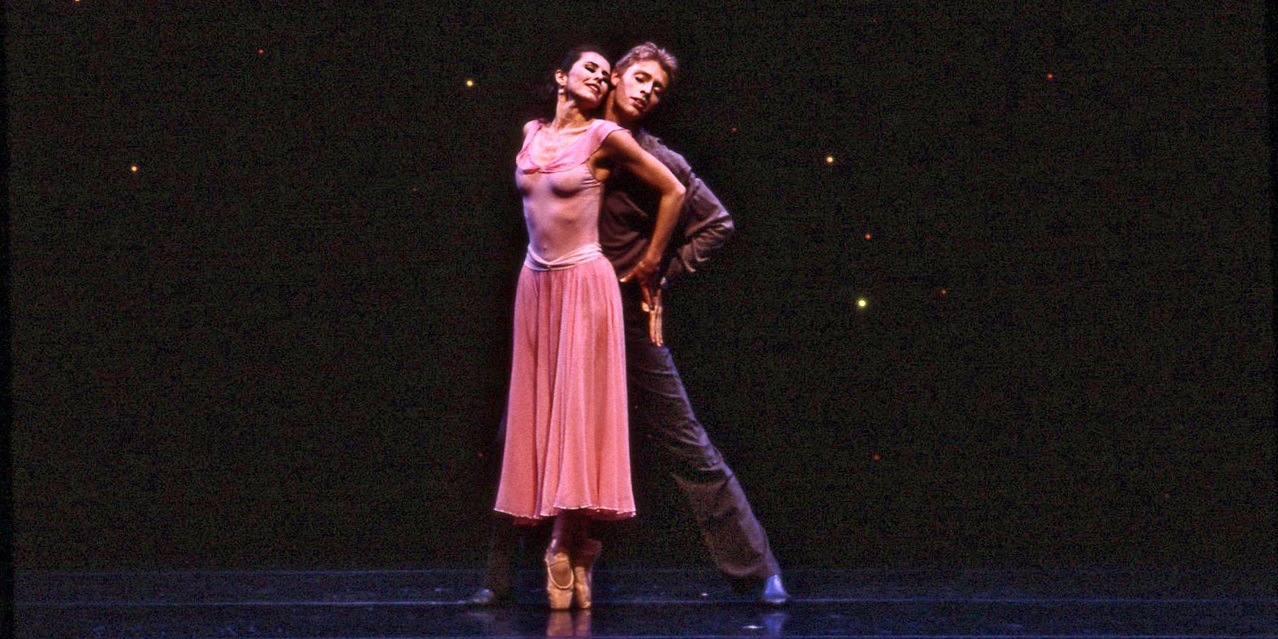

Featured image: Celia Fushille with Easton Smith in ‘Dream’ by Michael Smuin – Photo by Ken Friedman.