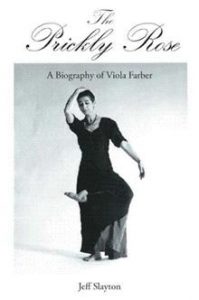

It is impossible for me to fail to recall Viola Farber, but I fear that because she did not share the amount of exposure as other more prominent male choreographers of her era, that Farber and her legacy are at risk of fading away. I have done what I know how to do to keep this possibility from occurring, but who will follow in my footsteps once I am no longer around. I am in my 70s and while very active, time is not on my side. I self-published a book in 2006 titled “The Prickly Rose: A Biography of Viola Farber”, I have put what copies there are of her work on DVD’s, and when asked, I have re-staged some of her choreography.

So, during this time of COVID-19 when performances, dance classes and other dance related activities have been cancelled, and LA Dance Chronicle is without events in which we can publish reviews and/or previews. I will take this time to continue to turn the spotlight on a modern dance legend of the 1960s through the 1990s.

The title of my book, “The Prickly Rose”, came from something that Farber told me was mentioned during an interview with her in 1995. She told me that a critic had compared her to a prickly rose while describing her in an article. She could not remember the writer’s name and all my research proved futile to locate just who that may have been. In reality, she could be like a beautiful rose whose stem was cluttered with large sharp thorns. If one wanted to get close to the rose, she/he had to be willing to get pricked or at the very least, remain mindful of and avoid the sharps. Farber the woman was extremely complex, and Farber the artist was no different. She could melt your heart; make you roar with laughter or destroy you with a single comment or glance. The latter, thank goodness was rare, but it was always there waiting to strike.

Born in Germany in 1931, Farber’s family moved to America in 1938 just prior to Hitler forbidding anyone from exiting “his” country. Her father was Jewish, and the family’s escape was aided by his employer. After spending some time in New Haven, Connecticut, they moved to the Washington, D.C. area where Farber lived until she moved to New York in 1953.

Farber was trained as a pianist during most of her younger years, and spent one year at the University of Illinois, Urbana-Champaign as a Music major. It was here that she took her first dance classes since leaving Germany. A year later she transferred to American University in Washington, D.C. also as a Music major.

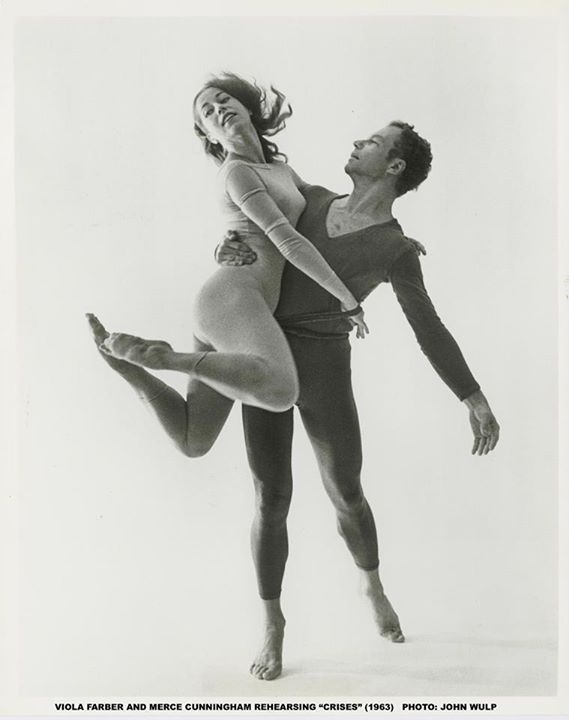

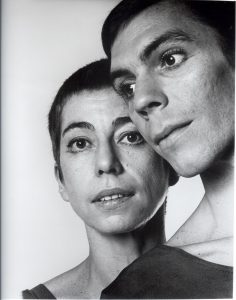

Her life totally changed when Farber saw a small photo of Merce Cunningham dancing with Anneliese Widman and decided to transfer to Black Mountain College located near Asheville, N.C.. There she studied dance with Cunningham, Katie Litz and music with Charles Olson. One of her friends there was an inspiring artist by the name of Robert Rauschenberg. She became friends with musician/composer David Tudor and painter Cy Twombly.

The Art Story website is a very good source to read up on the history of Black Mountain College. Here is just a small sample. “In 1952, John Cage along with the musician David Tudor staged the first “Happenings” at Black Mountain College. Cage conscripted Robert Rauschenberg, Charles Olson, M.C. Richards, and Merce Cunningham to perform various actions of their choosing at set times. The result was a cacophonous performance with no one center of attention. Poems were read, a lecture given, records played, dancers performed through the dining hall, and Rauschenberg’s White Paintings were displayed, but no one who saw the event describes it in the same way.”

Farber said in an interview with Donna Faye Burchfield that at the time she did not really like what Merce Cunningham was doing, but that she wanted to learn how to do it. And she did! Farber followed Cunningham and Cage to New York and became a founding member of the original Merce Cunningham Dance Company in 1953. She toured the world with that company performing in the original cast of approximately 20 of Cunningham’s works. She left the company in 1965.

I met Farber in 1966 when she was on faculty in the Adelphi University Dance Department where I was enrolled as a Dance Major. At the end of that year, she announced that she was no longer going to be teaching there, and without completing my degree, I followed her to New York City. I was awarded a full scholarship at the Cunningham Dance Studio located at the time at 498 Third Avenue and was fortunate enough to be asked to join the company just two months later. This was October of 1967.

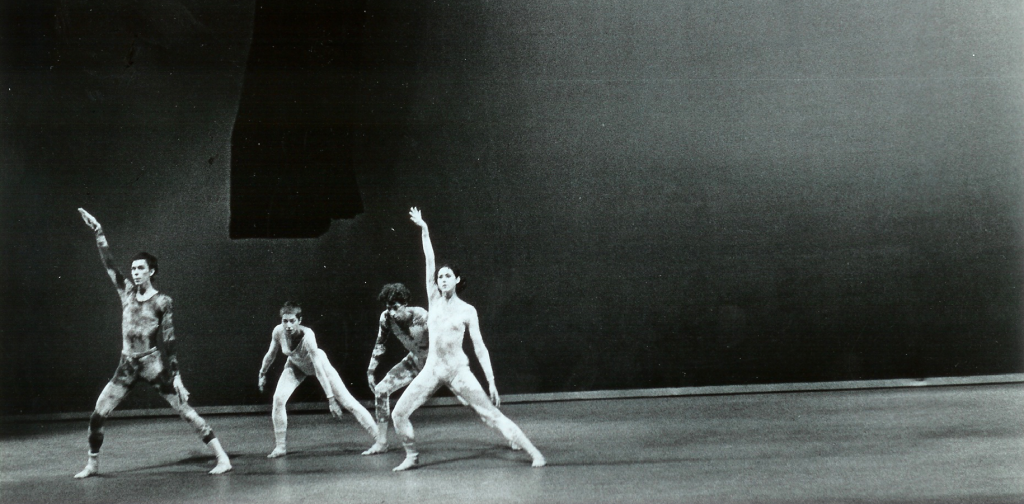

(L to R) Jeff Slayton, Viola Farber, Andé Peck, Anne Koren in “Poor Eddie” (1972) Choreography by Viola Farber – Photo by Mary Lucier

In 1969, Farber asked me to perform a duet with Mirjam Berns at her concert at WBAI Studios in Manhattan and in 1970 I made the decision to leave the Cunningham Dance Company and become a founding member of the Viola Farber Dance Company. I had been enamored of her work since I performed in a dance of hers at Adelphi, and although it was perhaps not the smartest career move, for me artistically, there was no other choice.

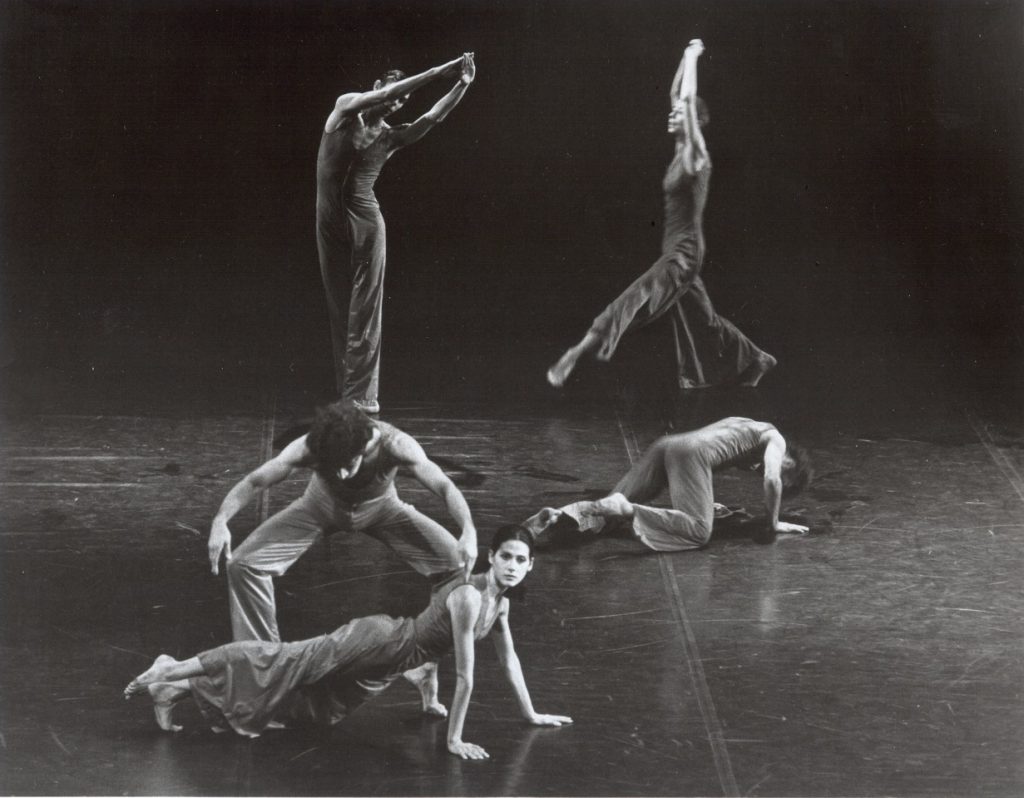

Viola Farber Dance Company in Willi I (1974) – Top row Jeff Slayton, Viola Farber – Bottom row Andé Peck, Anne Koren, Larry Clark – Photo by John Elbers

So, what was the difference between Merce Cunningham and Viola Farber’s work? In hindsight, for me personally the main ingredient was that Viola’s work had more to do with the people dancing it than Cunningham’s did. With Cunningham, we learned older works from the dancers who performed it and new work from Cunningham and the steps never changed unless directed by Cunningham. The exception was a dance called Field Dances (1963). There we made choices of when,m what order and where we performed certain phrases.

With Farber it was primarily the rule. We were constantly challenged to make decisions onstage and during the creative process of a new work. Her work included very structured improvisations on selected dance phrases, and sometimes we could join in on another dancer’s phrase. I told Sarah Swenson during a recent interview that I was most influenced by Farber’s choreographic style, and that the “organized chaos” that is in my work comes from my time with Farber’s company.

This is totally personal, but I felt more empowered, less restricted and totally at home while dancing Farber’s work, both in class and on the stage. Viola challenged our bodies, our minds and our creativity. She always asked us to dance full out; never to mark the movement except in situations where time was short. If we could not do a certain dance phrase of movement, Farber gave us the time to learn to and she taught us how to accomplish it. I did not have that same experience with Cunningham who rarely taught. He gave beautiful classes and made brilliant work, but I can not say that he helped me improve technically. This is not a criticism, just a fact. He was not interested in teaching, but in making dances and dancing.

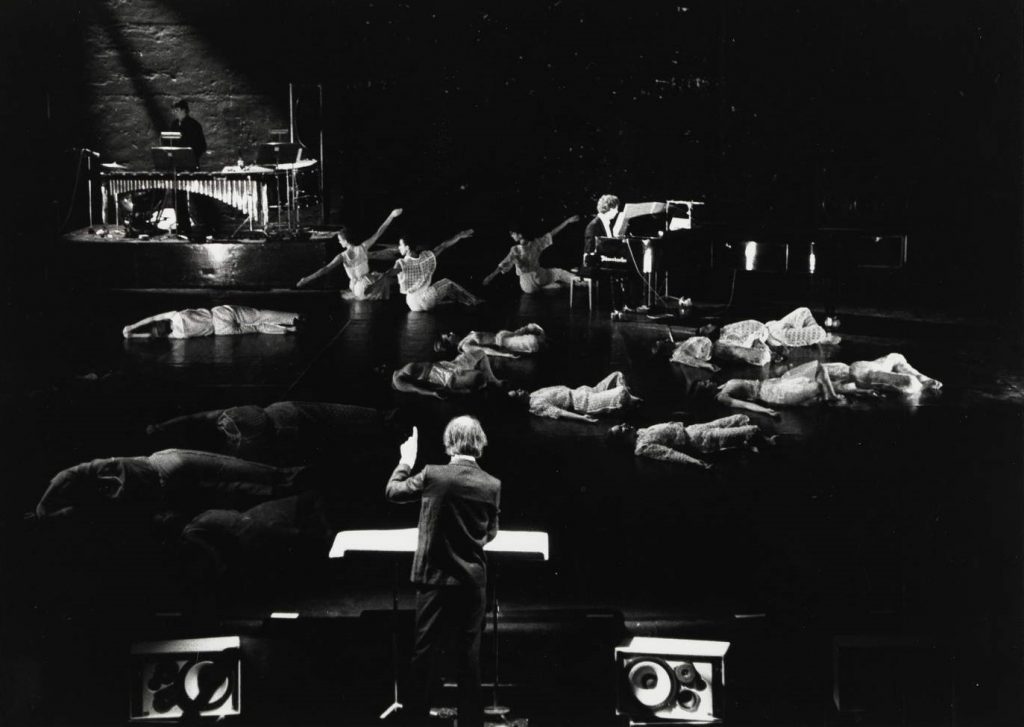

Farber ran her company in New York City from 1970 until 1981 when she left to become the Director and resident choreographer at the Centre national de danse contemporaine d’Angers (National Center for Contemporary Dance) in France. Several of the Americans in her company joined her in Angers and lived there for three years while Farber continued to teach and choreograph new works for her half American, half French dance company. It was a three-year contract, so in 1984 Farber moved to London, England and taught at The Place.

After receiving a grant from the John Simon Guggenheim Foundation, in January of 1984 Farber assembled together dancers from both America and France to perform in her made-for-television work titled January (26 minutes). I was honored to be in the cast of that piece, and until I screened it and the film Brazos River (1976, 60 minutes) at the Ft. Worth Dance Festival last year, it was never aired in this or any other country. January was Directed by Kevin Crooks in 1984, the Viola Farber Dance Company collaborated with TSW LTD to record her group work January at Dartington Hall in Devon, UK. Brazos River was a collaborative film with choreography by Viola Farber, music by David Tudor, costumes/set by Robert Rauschenberg, and featured the Viola Farber Dance Company.

Shortly after the making of January, Farber officially disbanded her company and remained in London until 1987 when she accepted the position as Chair of the Dance Department at Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, NY. Farber died on Christmas eve 1998 following two cerebral hemorrhages that left her in a coma for a month. I was at her bedside the entire month.

Some of you know that Farber – Viola – and I were married from 1971 to 1980. We separated in 1978, one of the reasons I move to the LA area, but I toured with her company on a part time basis until the company folded. In her will, Farber bestowed her archival material to me which I have protected as best I can. I have re-staged a duet that Farber choreographed for the two of us called Tendency for Repertory Dance Theater in Salt Lake City, Utah and a solo titled Clearing (1979) that she choreographed for dancer/choreographer Ze’eva Cohen will be performed by the Nancy Evans Dance Theatre this fall. I was also approached by a former student of Farber’s who now works in Rome about the possibility of re-staging two of Farber’s works, Sunday Afternoon (1976) and Doublewalk (1979), on students in Rome. This may change or be postponed due to what has happened around the world with COVID-19.

Farber loved dance and she loved to dance. She was unique in how she danced, and her work helped usher in the Post-Modern Era. She was considered by many to be one of the best teachers of modern dance in America during the years 1968 to 1998. People who kept their eyes and ears open while studying with her, became better teachers. She choreographed her classes and if there was a difficult phrase in the center work of her class, she prepared us for it during the “warm-up” part of the class. She rarely, if ever, threw any surprises at us, but was dedicated to teaching us how to dance, not to simply copy. She also taught us who we were as dancers. Farber taught us to dance like individuals, not like carbon copies of her.

What Farber felt most strongly was that when the people who performed her work were not dancing it, the work did not exist. When she died, I did not find a single copy of her work in her apartment or in her office at Sarah Lawrence College. I had to travel to New York City, London, Paris and Angers to collect copies and photos of her work. What there is, fits into three small boxes and sits on the floor of my guest bedroom in Long Beach waiting for the proper institution to preserve it for future generations of dance students and artists to see.

Written by Jeff Slayton for LA Dance Chronicle, March 18, 2020.

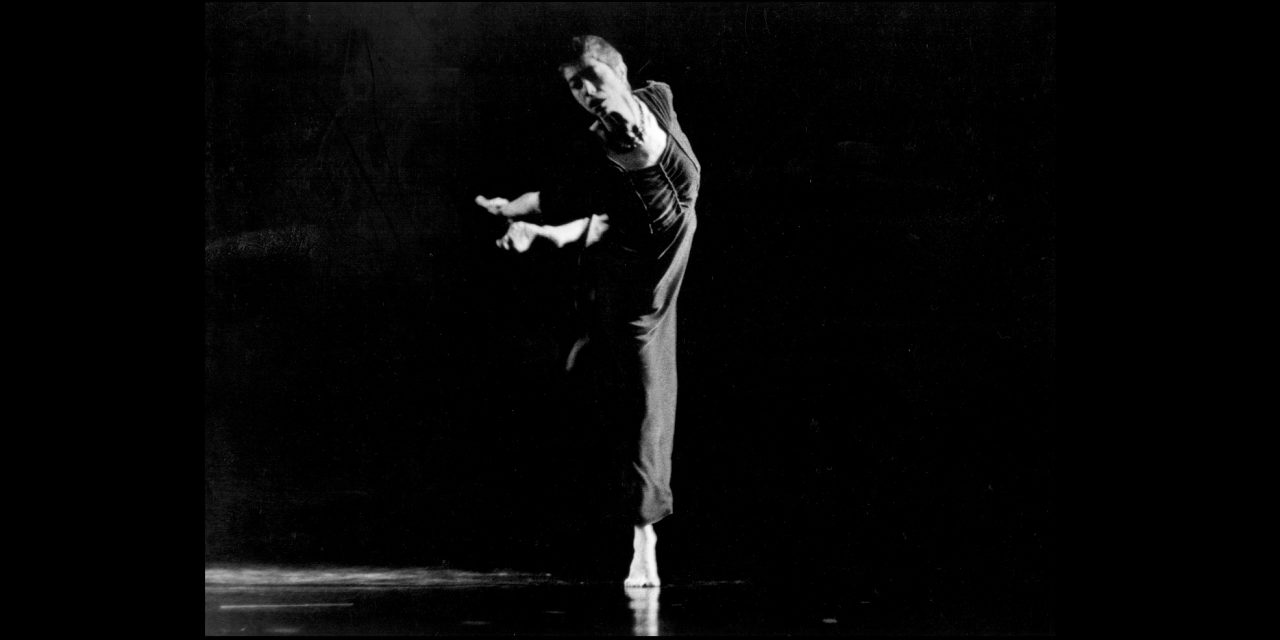

Featured photo: Viola Farber in Mildred (1970) – Courtesy of the Viola Farber Dance Company.

![“Rite of Spring” & “common ground[s]” at The Music Center’s Dorothy Chandler Pavilion in February](https://www.ladancechronicle.com/wp-content/uploads/2023/12/the-rite-of-spring-credit-maarten-vanden-abeele-0014-c1-440x264.jpg)