At 4:00 pm on March 19, 2023, the Ebell Club Los Angeles will host a celebration of the life and legacy of world-renowned ballerina Raven Wilkinson. The memorial event will be presented by Robyn Gardenhire, former ballerina and Founder and Artistic Director of City Ballet of Los Angeles, and Ariyan Johnson, UCI Dance Historian and multi-faceted artist. Tickets are $25 donations and $20 for Ebell Club members. To may be purchased HERE. Or call (310) 966–0505

Gardenhire was inspired to honor Ms. Wilkinson’s life and legacy with a memorial event when she died in 2018, but the pandemic forced Gardenhire to delay her plans. She hopes this celebration will bring Wilkinson’s life before a greater audience and enlighten them about the presence and contributions of black people in classical ballet.

In my conversations with Gardenhire and Johnson, I asked what they thought was the true legacy of Ms. Wilkinson’s career? Quite poignantly, though neither Gardenhire nor Johnson had ever met Ms. Wilkinson, both were deeply impacted by her perseverance. For Robyn Gardenhire, Wilkinson’s persistence has personal resonance. Gardenhire is an accomplished ballerina in her own right—having danced with Joffrey II, Cleveland Ballet, American Ballet Theater (ABT), and the White Oak Project via an invitation from Mikhail Baryshnikov himself. During her performing years, she experienced the same difficulties Wilkinson did as a qualified ballerina in black skin. Gardenhire, likewise, had to stand in the resolve that she was worthy of being embraced for her talent and not dismissed because of her skin color.

Ariyan Johnson—a consummate artist and scholar—was drawn to Wilkinson’s perseverance to do the art that made her heart sing and be a black woman in ballet (despite being told—as black dancers often are—that she should pursue African dance instead). Johnson was also inspired by her refusal to allow other people’s issue with her skin color to become her own. If you look up Raven Wilkinson, she is celebrated as the first black woman to receive a contract to dance for a major ballet company. However, Johnson believes acclaiming Wilkinson’s career for this reason “diminishes the brightness and brilliance of her artistry [and the] actual injustice” that surrounded her career. And I agree. The remarkableness of Wilkinson’s career is not that this obviously and undeniably gifted ballerina was the first African-American woman to dance with a major ballet company. That fact is more an indictment on the culture and society that surrounded her and their destructive fixation with skin color. The remarkableness of Wilkinson’s career is that, despite the society and culture in which she lived, she did the work and exercised the persistence to earn a spot (becoming a soloist with the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo in her second season) in a major ballet company.

When black “firsts” happen in the ballet world, history whips out her pen with pride and feverishly records the momentous occasion. Societal bells chime laudingly and festive confetti fills editorial spaces. And it is right for us to do this. It is not right because another black dancer joined the ‘hall of firsts.’ It is right because a remarkable artist persisted in their merit, received their due, and became a first despite the ballet world’s conscious or unconscious objections. But as Johnson highlighted, to only celebrate a black dancer’s firstness is to diminish the injustice surrounding their career.

When Wilkinson began auditioning for the Ballet Russe de Monte Carlo, her prowess as a ballerina was quickly noticed, yet she was encouraged to consider an African dance company and even told by a friend that the Ballet Russe would not be able to hire her because of her race. But Wilkinson persisted, earned a spot in the company in 1955, and was promoted to soloist in her second season. Her ballet career was compromised, however, as the Ballet Russe toured the South. Once audiences discovered she was black, Wilkinson began to encounter increasing discrimination, and even threats on her life when the Ku Klux Klan would surround—and even invade—the theater where she was performing. To protect her, company management advised Wilkinson to only tour with the company in certain areas. Exasperated, she left the Ballet Russe in 1961 and later joined the Dutch National Ballet. But homesickness brought her back to the United States in 1974. However, she was never accepted into a ballet company again in the U.S. She finished out her performing career with the New York City Opera.

Ms. Wilkinson is celebrated because she was a brilliant artist who should be celebrated for her contribution to the ballet story. Period. But we note her firstness and the issues that surrounded her skin color because these elements speak to the difficulties black ballet dancers continue to navigate over 50 years after Ms. Wilkinson began her ballet career, including former American Ballet Theater principal Misty Copeland, who speaks openly about the still treacherous path of being a black dancer in professional ballet.

On the other side of highlighting the fact that Wilkinson was the first black woman to join a major ballet company, it is imperative that we interrogate why that is and why it hasn’t changed as much as we’d like to believe since her career? Ask different people this question and you quickly realize that the reasoning for the sparseness of black dancers in major ballet companies is a moving target. For Wilkinson and other dancers of her era, it was unapologetically about skin color. In contemporary society, we claim to have moved past skin color—despite the fact that any passing glance at rosters of major ballet companies proves otherwise. Ask some and they say it’s because black bodies are curvy and muscular. Others claim it’s because black people have flat feet. Others believe black women cannot embody the soft and feminine qualities intrinsic to the ballet form. And still others hold that black skin disrupts the aesthetics via uniformity so venerated in ballet. The reasoning provided from person to person may change but the consistent outcome of each reason is “No” to black skin.

I was talking with a friend about this issue and she brought up tradition, upon which I asked, “What is the actual ballet tradition(s) we are trying to preserve?” In all of the collective choices being made in the ballet world, are we working to actually preserve that tradition or are we engaging in personal aesthetic preferences that keep others out for reasons that actually have nothing to do with the actual art form? Are curvy bodies really that detrimental to ballet if the body can execute the movement and accomplish the lines? Is a single skin color the only way we can imagine achieving uniformity? And is that really a good enough reason to keep otherwise qualified dancers out of a company? Do all black people actually have flat feet? And is a flat foot truly an insurmountable conclusion to a ballerina’s career aspirations if she is able to persist and execute the choreography at the highest level? Are we really saying that we are willing to stop a qualified dancer’s entire career because of the shape of their foot? What are the things that actually make ballet, the dance form, ballet? Are we really saying there is no room for diversity in the ways those essential things are expressed?

Raven Wilkinson loved ballet since she saw a performance at the age of five. She decided to pursue that love and persisted until she achieved it. She persisted until she earned a spot in a major ballet company. There are others who continue to come behind her, who are following in her legacy and doing the work, persisting to take their place in the ballet story. Since Wilkinson, only 11 black dancers have reached the pinnacle of ballet, the principal dancer (except for Arthur Mitchell who became a principal with the New York City Ballet in 1955): Tony Williams, Boston Ballet (1964), Debra Austin, Pennsylvania Ballet (1982), Lauren Anderson, Houston Ballet (1990), Albert Evans, New York City Ballet (1995), Desmond Richardson, American Ballet Theater, (1997), Tai Jimenez, Boston Ballet (2006), Misty Copeland, American Ballet Theater (2015), Calvin Royal III, American Ballet Theater (2020) Chyrstyn Mariah Fentroy, Boston Ballet (2022), Jonathan Batista, Pacific Northwest Ballet (2022), and Nikisha Fogo, San Francisco Ballet (2022). But there are many, many more beautiful black ballet dancers out there and they are ready and waiting to move us all past the days of “firsts.”

WHAT: Celebrating The Life of Raven Wilkinson

WHEN: March 19, 2023 – 4:00 PM – 7:30 PM

WHERE: Ebell Club of Los Angeles – 743 Lucerne Blvd., Los Angeles, CA. 90005

TICKETS: Donation of $25 – Ebell Club Members $20 – To purchase tickets, please click HERE. Or call (310) 966–0505

Written by Marlita Hill for LA Dance Chronicle.

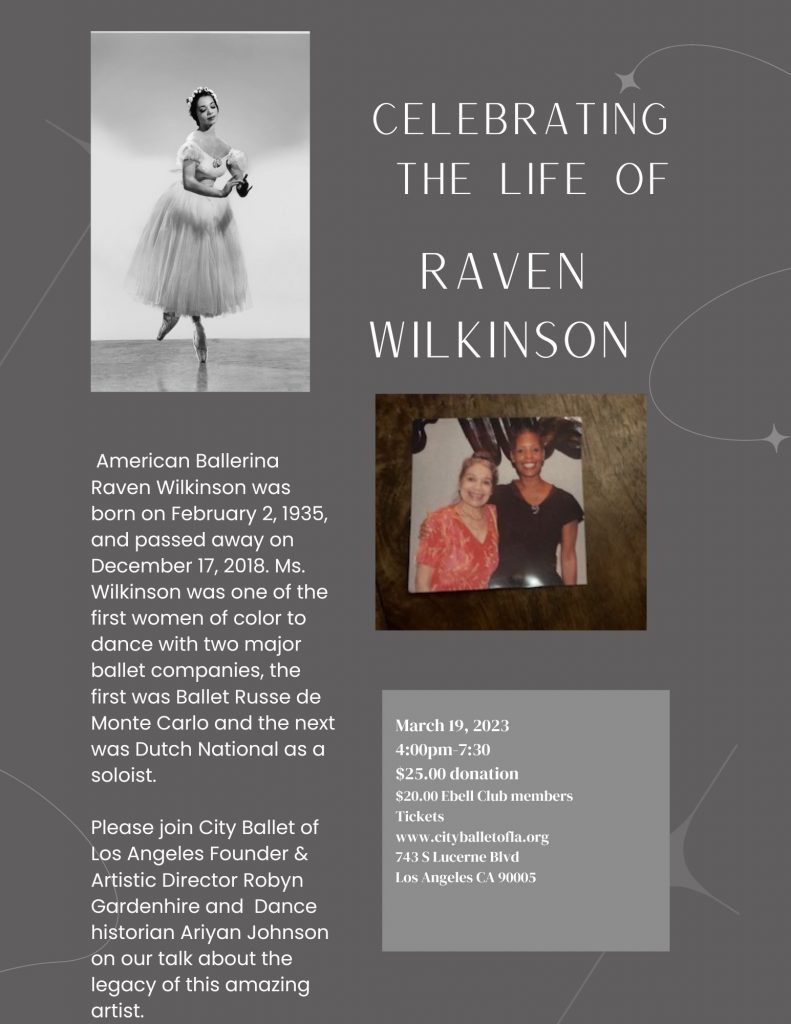

Featured image: Raven Wilkinson in Les Sylphides – Photo courtesy of the Ebell Club of Los Angeles