It wasn’t breakfast at Tiffany’s, but a stroll through Van Cleef & Arpels that is credited with inspiring George Balanchine’s only three-act, non-narrative ballet Jewels. At its New York City Ballet premiere in 1967, Jewels was a rare creature—a hit with ballet audiences, deemed a masterpiece by New York’s hard-to-please critics, and adored by the NYCB dancers.

A regular part of NYCB’s repertoire, LA has intermittently seen the middle Rubies section, most recently as part of Los Angeles Ballet’s repertoire, but the full, three-part ballet receives its first LA performances when the curtain goes up at the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion on the Mariinsky Ballet.

When it arrives, the LA audience may include some particularly knowledgeable members. Former NYCB dancers who performed Jewels who now reside in LA and are part of LA’s vibrant dance scene include Jenifer Ringer, James Fayette, Colleen Neary, Adam Luders, Benjamin Millepied, Sebastien Marcovici, Janie Taylor, and Zippora Karz. Several shared their insights into the ballet and their memories of dancing Jewels during their NYCB careers, including one of the original principals, Patricia Neary.

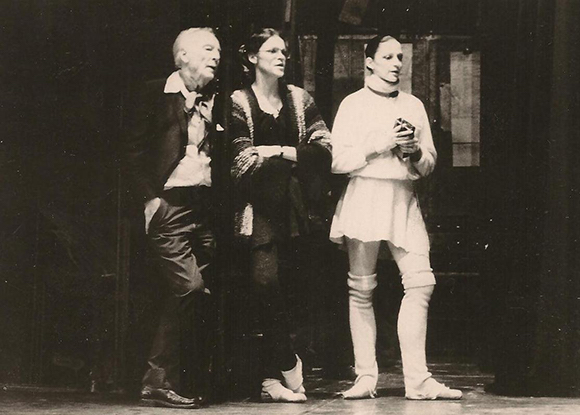

Rubies opens on a glittering semi-circle of red-costumed dancers, suggesting a necklace centered around a woman defiantly on pointe. It is one of the ballet moments that feels so audacious that it often provokes applause before anyone dances. Not only was the subject Jewels, Balanchine set the ballet’s solos on dancers recognized as the crown jewels of his company at that time: European-trained Violette Verdy and Karin von Aroldingen in Emeralds, Suzanne Farrell with Jacques d’Amboise in Diamonds, and in Rubies, Patricia McBride paired with Edward Villella and Patricia Neary as that center gem.

“We had just returned from summer break and learned Balanchine was beginning a new ballet,” Patricia Neary recalled, “We found out later that he had set the Diamonds pas de deux on Suzanne Farrell and Jacques d’Amboise over the summer, but the company began with Rubies, and it was amazing how he worked. Balanchine finished Rubies in five days He would work for a time in one studio with Rubies, then walk into another studio and continue setting choreography for a different section, working in different music with different dancers. He was a genius. He hated the word, but I don’t care. He was so fast and so knowledgeable.”

While other dancers mentioned other roles, they would have liked to have danced, Patricia Neary had no such thought. “I had the best part. Why would I want to dance anything else?”

Several NYCB alum commented that the opening ballet Emeralds is often overlooked amid the razzle dazzle of Rubies and opulence of Diamonds.

Jenifer Ringer who now is Dean of the Colburn School’s Trudi Zipper Dance Institute was coached by Karin Von Aroldingen, on whom Balanchine set a leading role in Emeralds.

Ringer remembered Von Aroldingen, who could be very a very athletic and dynamic dancer as turning herself inward, “making the part about the quiet, mysterious, gestural depiction of beauty and music.”

“I think that Emeralds, as a ballet, invites the audience into a world that has been set up by the music, choreography, costumes and stage craft. It is perfect that it is the first ballet, because the viewer must ‘lean in’ in a sense, and connect the subtleties of the partnering, patterns and gestures and how those inform the world that is Emeralds. It is like a wash of music and light that the dancers inhabit for a time, and they invite the audience to enter, spin and feel and experience, and then end their involvement in the ballet not really as a sentence with a period or an exclamation point but more of a dot-dot-dot that leads you into the very extroverted section of Rubies. In my opinion, Rubies ends with an exclamation point. Diamonds ends with a very satisfying period.”

Patricia Neary’s Rubies role became known as the “Tall Girl,” a part her sister Colleen Neary later danced. Both sisters are repetiteurs for the Balanchine Trust and are among those designated by Balanchine personally to stage his ballets.

“I grew up with that ballet and first danced in the Diamonds corps because I was tall,” Colleen Neary said. “Later I was cast as the ‘tall girl,’ the part my sister danced. I was thrilled because as the originals retired, the leads in Jewels generally were reserved for principal dancers and I was a soloist, but I was always quick with choreography and I was tall which makes Rubies’ opening so powerful.” As co-artistic director of Los Angeles Ballet, her deep history with Rubies influenced the decision to include that ballet in LAB’s repertoire.

Now dividing his time between the Royal Danish Ballet, New York and Los Angeles, Adam Luders was an admired danseur noble who acquired the Jacques d’Amboise role in Diamonds, partnering ballerinas including the original, Suzanne Farrell in the challenging Diamonds pas de deux. While the danseur in that pas de deux receives attention, Luders reflected on the partnering challenges throughout the three ballets including in that climactic pas de deux because “Balanchine wanted the man’s partnering to be almost invisible.”

Working with Balanchine, Luders found “it was extraordinary clear how important both the woman and man are in setting a pas de deux like Diamonds, especially a man because of the partnering. For example, in the last partnered turn in Diamonds before he kneels and kisses her hand, the entire pas deux can be utterly ruined if he comes schlepping towards her, using two hands and squatting.” That approach might be easier, but Luders believes to the knowing eye “it gives the whole pas de deux a look of amateurism.”

James Fayette and Ringer both echoed Luders’ comments about the partnering challenges in Jewels, particularly in Emeralds where Fayette noted “with Balanchine ballets and the style of NYCB, male dancers are trained to demonstrate as little effort in partnering as possible. The focus is of course on the woman and you must provide the opportunity for her to shine in every step but not be seen making any effort or add anything extra to the execution.”

“The partnering in Emeralds takes that to the extreme and I was always told by the ballet master to do less while the ballerina was asking me to help her more. The male partners of Emeralds are the unsung heroes of the ballet because their success, more so than most other ballets, are to make the ballerina shine but themselves to fade into the background of her dancing. This was one of the most challenging pas de deux that I ever had to do, but for reasons unique almost only to Emeralds,” Fayette explained.

As one of the ballerinas supported by partners in Emeralds, Ringer affirmed that the male dancers succeeded more, the less they were noticed. “I just want to say, the only reason the ballerinas look as beautiful as they do is because the men are transitioning them from one movement to the next in such a fluid way,” Ringer explained, “The partnering is very difficult and very subtle, but you wouldn’t really know it because they make it look so easy.”

The New York City Ballet may be Jewels’ home, but the Mariinsky is something of an adopted one. Few companies can field the 66 dancers required for Jewels and fewer still have the depth of dancers—from the spectrum of soloists to the corps de ballets—able to convey three different ballet flavors. Originally set on the Russian company in the 1990s by four repetiteurs from the Balanchine Trust, it has become a fixture in the Mariinsky Ballet’s repertoire.

With roots going back to the Russian Tzars when the company was the Imperial Russian Ballet, after the revolution and the rise of the Moscow-based Bolshoi Ballet, the company was first renamed Soviet Ballet and later the Kirov Ballet. In more recent political climes, it became the Mariinsky Ballet, named for its legendary home theater. Before Balanchine immigrated to Europe and eventually the U.S., he was a student and in the corps at the Mariinsky, so there is a circularity to the Mariinsky’s embrace of a Balanchine work that pays homage to his experiences in European, American and Russian ballet.

It’s hard to capture in words the enthusiasm and smiles in the voices that responded to requests for comments on their memories of NYCB and this ballet:

Colleen Neary was a child when her older sister Pat debuted in Rubies, she vividly described the opening party hosted by Van Cleef and Arpels, the excitement, the sense that something extraordinary had just occurred.

Benjamin Millepied who danced the featured male part in Rubies paid his own homage, naming a work Gems and establishing an ongoing relationship with the jeweler that provided Balanchine’s inspiration.

Fayette articulated the deep impact growing up with Jewels had on his generation at NYCB and the affiliated School of American Ballet.

“I was a student at the time and this was one of the first Balanchine ballets that we were really taught to dance. We all fell in love with it despite its serious challenges. I remember late one night when the accompanist was practicing the music in a dance studio, a few dancers including myself came upon the music being played and started to go through the choreography in the studio still wearing our street clothes. Some other students came across what was happening and joined in. This kept happening until we had almost a full cast of dancers rehearsing full out the complete ballet in our street clothes late at night to the accompanist’s practicing after having danced all day. We just could not get enough of the experience. I have so many great memories attached to this incredible piece of art and I look forward to revisiting many of them when we get a chance to see it again at the Music Center.”

Casting at https://www.musiccenter.org. Music Center, Dorothy Chandler Pavilion, 135 N. Grand Ave., downtown; Thurs.-Sat., Oct. 24-26, 7:30 p.m., Sat.-Sun., Oct. 26-27, 2 p.m., $34-$138. https://www.musiccenter.org.

Written by Ann Haskins, October 23, 2019

To visit the Mariinsky Ballet website, click here.

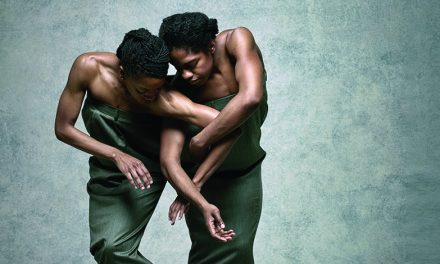

Featured image: Nadezhda Batoeva and Kimin Kim – Photo by Natasha Razina