“America the Beautiful” is no longer a common phrase used to describe this country. Environmental irresponsibility is poisoning the land and unequal opportunities are making it harder for immigrants to thrive. However, there was a time when people looked to the United States with hope and wide-eyed wonder. Choreographer Victoria Marks’s Pastoral, which enjoyed its world premiere at the Odyssey Theatre between February 7 and 9 as part of the 2020 Dance Festival (January 10 – February 9) explores these themes by bridging the past with the present through creative storytelling tools. The 60-minute piece is bold, blunt and entertaining, but occasionally tends to feel choreographically stagnant.

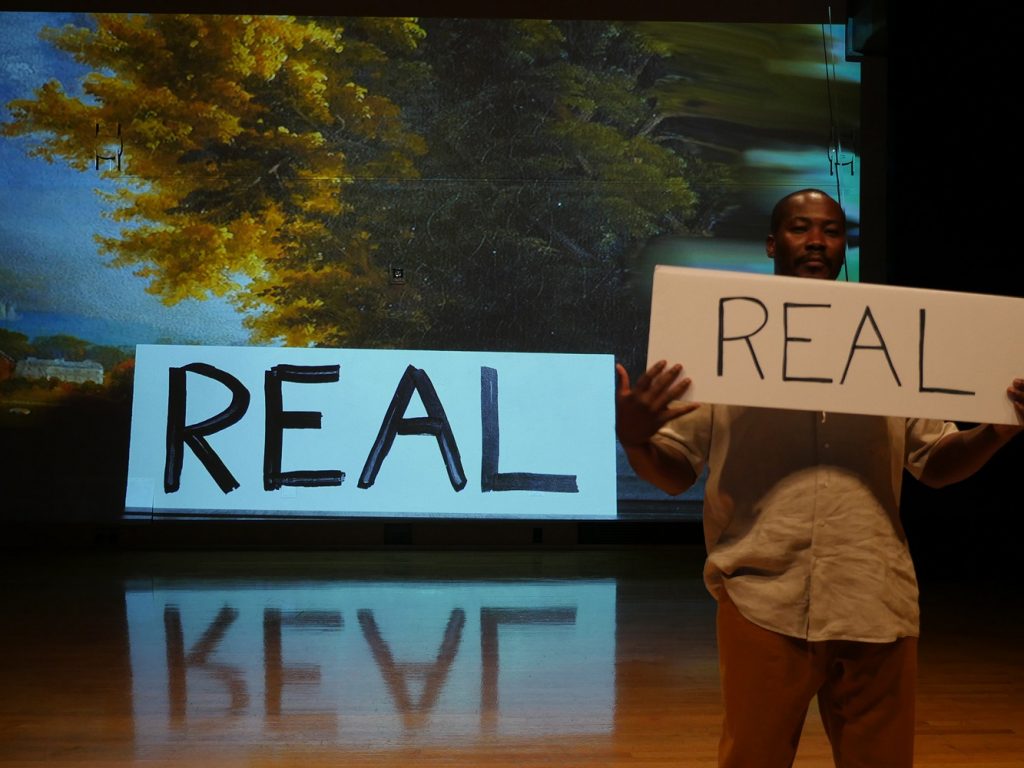

Basing itself in Appalachian Springs (1944) created by Aaron Copland for Martha Graham, the work begins with Copland’s “Fanfare for the Common Man,” while a painting of the great outdoors is projected in the background. The six-person ensemble (Dezaré Foster, DaEun Jung, Aaron Mason, Alexx Shilling, Willy Souly, and Tom Tsai) takes turns posing with arms spread open and legs wide apart, almost as if on horseback, waiting to ride into new opportunities. The music wanes several times and the picture zooms out to reveal the painting’s small size and frame, taking away from its grandiose presence all along the black box theater’s back wall. Despite this, the performers only try harder; their stances broaden as if to indicate their willingness to be as open as possible in order to receive anything that may come their way. Their shoulders bend as they struggle with the weight of the responsibilities they need to take on in order to achieve their dreams. The image eventually distorts to make it seem as though Jung, who led the troupe through the first movements is now riding fellow dancer Tsai, taking advantage in whatever way she can in order to survive.

This first piece of choreography fully encompasses the tone of the dance: part-mocking, but mostly serious. Audience members watch the performers unite for a common cause through moments of synchronization, struggle individually in chaotic scenes that eventually entangle their fellow dancers, and continuously fail without ever giving up hope.

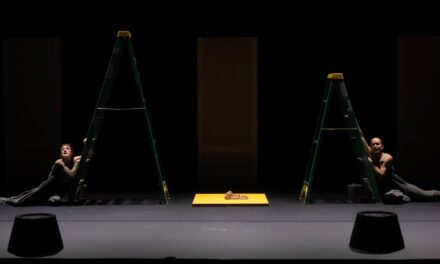

One memorable segment involves the slow disappearance of a small square of light (design by Arsenio Apillanes) cast down onto the stage to represent a shrinking plot of land. As an instrumental version of Gene Autry’s “Don’t Fence Me In” ironically blares overhead, the dancers attempt to share it, skipping along in the middle like good-natured cowboys at a hoedown. The moment soon devolves into the Wild West as the light shifts to a new location — a sign it’s time to move and start from scratch — reappearing smaller than before and forcing the group of six to push and shove until they begin to exclude one another from the space.

Puppeteering (Islan Hansen and Tucker Marder) plays an important role in the piece, by both highlighting humor and adding an extra element to the dancing. A miniature theater hovering on the outskirts of the stage was used to show images of properly labeled cardboard mountain cutouts pushed in and out of the frame by one of the puppeteer’s (also labeled) hands. At times, performers’ faces were seen clearly reflected on the projections, creating a sense of duality — as Tsai saw himself on the mountains, he made eye contact with the audience, forcing them to wonder where they saw themselves belonging in today’s landscape.

Clouds were a significant recurring motif. Throughout the course of the evening, they grew faker and faker until they appeared to be made out of plastic, creating a sense of disillusionment, which cast a gloomy shadow over the entire production. The dancers pushed in unison against the clear, realistic sky, seemingly resisting its presence. Unable to embrace its freedom, they turned on their heads, continuing to push while falling from whatever great heights they had reached.

Marks’s modern choreography cleverly connected with the abstract narrative elements throughout. A ship rocking violently in a stormy soundscape (designed by Daniel Corral) represented an immigrant’s journey to the new land and was creatively portrayed by Foster controlling a wooden, ship-shaped foot rocker, tightly zoomed in on by the projector. A simple and not uncommon scene consisting of the six dancers holding hands to form walls felt new when the ensemble was shown taking turns facing toward and away from each other to represent selective inclusion and isolation. However, after an evening rife with symbolism, some of the imagery began to feel a bit clichéd. Marks’s scenes in outer space particularly gave the piece a sense of vastness that had the potential to pull viewers out of the intimate theater.

Pastoral takes the early 20th century concept of Americana worship and shatters it — rightfully so. Though things have never fully been fair, the once tangible idea of “making it” has become almost entirely fantastical, as we struggle to find out place in this land.

Written by Lara J. Altunian for LA Dance Chronicle, February 13, 2020

Featured image: PASTORAL choreographed by Victoria Marks – Madeline Nobia