According to the program notes, “The two artists engage in a dynamic and intimate dialogue using their bodies and musical instruments, exploring a range of possibilities in their relationship within the piece.” This perfectly captures what happened during the show, yet also does not come close to explaining the visual or auditory impact of the piece designed by these two very different and also strangely similar artists. Let me unpack that last statement.

The work was first presented at the Broad and then further developed for L.A. Dance Project (LADP) into the 50 minute version presented. It flew by as the pace was brisk and the performers were entirely focused on each other bringing the audience into their world to wonder what would happen next. There was a talk-back after the show which shed some light on the hows and whys of the work. We were told that it began as a series of improvisations between the two artists and then settled into this version presented to the public. There was a lot going on between the two.

The relationship between solo dancer and musician accompanist is extremely intimate and delicate, astute and sensitive. The awareness one needs for the other is intense. During this show we were allowed to witness that bond and more. We got to see that bond stretched to its limits and even broken, only to come together again in a beautiful and loving way at the end of the work. They did this in a very clever and articulate manner, through sound and movement.

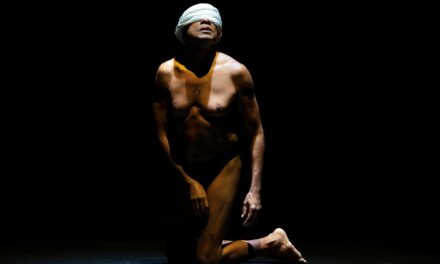

It was not just a dancer interpreting the sounds that a musician makes, nor a musician ‘marking’ the moves of a dancer. There were sonic landscapes that the dancer, Jobel Medina, had to endure and traverse. Like a test of strength in order to be worthy of admittance to a sacred clan. There were instances where the musician, Elliot “L” Sellers, was manipulated and caught off guard, rendering him helpless without the comfort of his drum sticks or bow and cello. There was a great deal of humor throughout as well. At least I thought it was hysterical. At one point, Medina is fed up with the drums beating him into physical exhaustion and he proceeds to take Seller’s drum kit apart. Sellers is dogged in his drumming on any instrument left in his vicinity and as Medina takes the last one, Sellers stands and follows him, continuously drumming a constant beat as they both exit through the side door to the parking lot and all around the building to enter through the lobby where the audience enters. We could hear the entire exodus and route as the drumming never stopped. This was hysterical and worthy of an “I Love Lucy” sketch. It was also a testament to very difficult drumming en-voyage and spoke of high-level mastery.

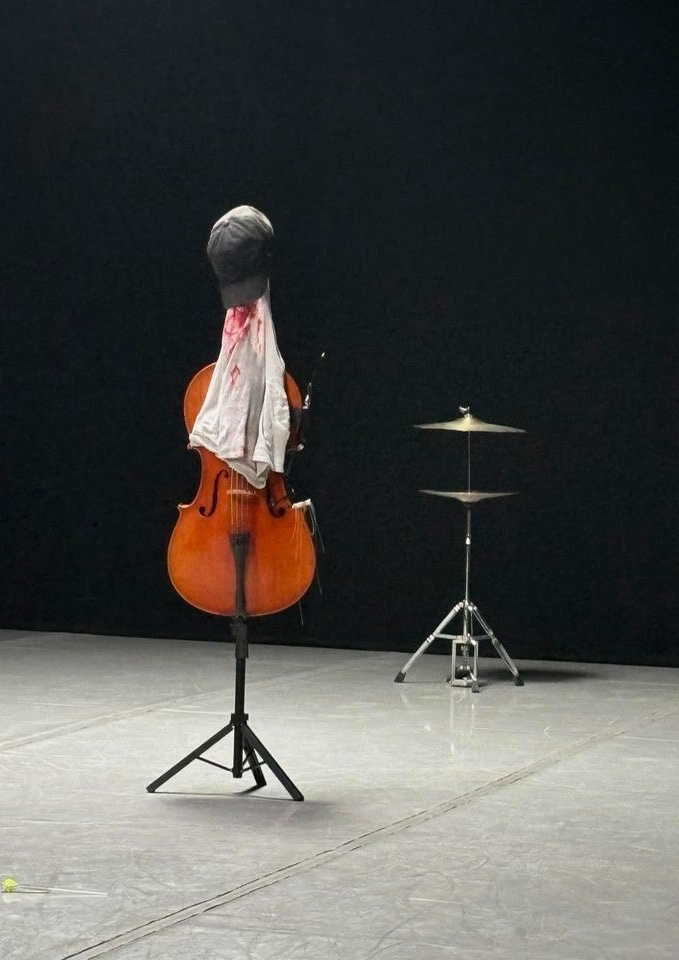

The beginning of the work was in silence as Medina entered the space and took it all in. Sellers was sitting among the audience and his stretching into his role came as a surprise. What was elegant about the beginning was letting the audience take in the movement in silence. Then slowly having Sellers join preparing the stage, the set, the room for what was to come. When Sellers did hit the drums, it was with a vengeance reverberating throughout the entire building. It was immediate and powerful. The movement “language” employed by Medina was changed and augmented by whatever instrument Sellers was using. The drums brought forth a different quality than the Cello, both different from the silence.

The Lighting by Stefan Colson and Sam Wilkerson was spot on as well. The stage was set on a horizontal rectangle from right to left with the drum kit at one end and the chairs for the audience aligned around the edges of that rectangle. It brought the audience in close to the action of the two performers and also served to limit the periphery of vision. The lighting was set above this area in a rectangular box of its own and reminded one of a boxing ring with bright white light being focused down on a very specific area directly underneath. It also served as a kind of forensic light of the type used for dissecting cadavers in anatomical universities. There was no corner unlit, no movement unseen. This lurid array changed to a red saturation towards the end and commented strongly with the emotion of the work. There was also an underwater effect which occluded the visuals to a certain degree rendering the watching of the action a voyeuristic endeavor.

We witnessed the two antagonize each other, then test each other, communicate with each other and finally come together and understand that there was no other, but only a shared single existence experiencing the same stimuli and trying to make sense of it. A lesson for us all.

To learn more about L.A. Dance Project, please visit their website.

Written by Brian Fretté for LA Dance Chronicle.

Featured image: Jobel Medina (standing) and Elliott Sellers in IMMDED IMMGEWD – Photo by Elle León Nostas.