Michelle Dorrance, artist, dancer, musician, choreographer, collaborator, company director, unifier, and, most important, tap lover, is everywhere! She and her company, Dorrance Dance can be seen all over the world thanks to a jam-packed touring schedule that includes Los Angeles’ Ford Theater on September 6, Santa Barbara’s Arlington Theatre on December 5, Northridge’s Soraya on December 11, and Berkley’s Zellerbach Hall on December 14 and 15.

She is a 2018 Doris Duke Artist, 2017 Ford Foundation Art of Change Fellow, 2015 MacArthur Fellow, and 2012 Princess Grace Award winner and earned a Bachelor of Arts from New York University and an honorary Doctor of Arts from the University of North Carolina. She has more awards and acknowledgements than I can list, and she has choreographed for or collaborated with a list dance luminaries that includes Dormeshia Sumbry-Edwards, Derick K. Grant, Maude and Chloe Arnold, Nicholas Van Young, Bill Irwin, Lil Buck, Tiler Peck, Jillian Meyers, Ephrat Asherie, and Toshi Reagon. Her commissions include Martha Graham Dance Company, The Joyce Theater, New York City Center, Vail Dance Festival, American Ballet Theatre, and Works & Process at the Guggenheim.

Ms. Dorrance was born and raised in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, where she was mentored by groundbreaking youth tap educator, Gene Medler and raised by parents who were educator committed to developing youth in their community. Her father was a soccer coach, and her mother was a dance teacher. She speaks of them with pure adoration and respect. Throughout our interview she credits them for all that she has accomplished. Her parents and Gene Medler were clearly a three-legged stool that supported, encouraged, and facilitated her artist growth and her commitment to dance as a tool for social change. for all that studied under many of the last hoofers of the jazz era.

As a New York City-based artist for over 25 years with performing credits with a long list of notable tap companies and productions including Savion Glover’s ti dii and the Off-Broadway sensation, STOMP. 2011 saw the birth of Dorrance Dance Company to “help audiences view tap dance in a new and dynamically compelling context while honoring the Black American legacy of the art form”.

While it is my preference to interview artists in person or via zoom Michelle was not available to do either and I was initially concerned that I would not be able to establish a personal connection with her. I was absolutely wrong! Her energy, commitment, and excitement about tap dance jumped through the phone. We immediately established a connection based on our mutual love of tap and a long list of mutual friends in the tap world. Initially, she was interviewing me, a testament to her humility. I was shocked that she had done some research and asked if she could sit down and talk with me at some point. I am looking forward to that time.

Leah: Hi Michelle

Michelle: Hi, I’m going to try not to ramble.

Leah: Ok. (laughter) You ramble as much you want. I’m going to do my best to take notes and learn about you. I’ll ask questions as fast as I can because I know you have lots of things to do and other interviews to do too.

Michelle: I am here for you. I’m grateful to get to chat with you. How cool. You’ve done all kinds of amazing and brilliant things.

(Short discussion ensues about various tappers we both know.)

Leah: Thank you. I’m going to ask you some questions and then I’ll tell you a little about me if you have time. (laughter)

Michelle: I looked you up. I do believe you did something with Tap Dance Kid. Is that right?

Leah: Yep, I was Dance Captain on the original workshop and Broadway company.

Michelle: Oh my gosh. On the original. You were there when they brought Savion in?

Leah: I was there long before Savion.

(Short discussion about Tap Dance Kid.)

Leah : Michelle, tell me about your music background and the role it plays in your tap dancing. Many tappers have said the percussive sounds are the music and prefer to tap acapella. In your creative process, which comes first, the music or the tap dancing?

Michelle: “Coming up as a dancer my mom was a professional ballet dancer and she started a school and my father was a soccer coach, actually a really notable women soccer coach. He just retired, but they were both brilliant at what they did. And I was not great. at either ballet or soccer. I loved dancing and I loved playing soccer, but I immediately gravitated towards tap dance because it was a musical form. My mom says my aptitude wasn’t in dance when I was really young but when I was two, I memorized a whole album of Christmas songs and I didn’t even know what every word meant. You know, when you’re a baby or a kid, you just make up the way to say things. My mom would say, I said, “ this the season to be Cholly,” like Cholly Atkins. She said I would memorize music, and she couldn’t believe it. She sent a cassette tape to her cousins in Texas, and they said, “our kids aren’t doing things like that down here.” My mother said she could tell I loved music. It made sense that this was my gift in terms of dance. I wasn’t particularly graceful. Everyone in ballet class called me noodle arms and all these funny nicknames, but I had an exceptional tap dance teacher and mentor, Gene Medler who started the North Carolina Youth Tap Ensemble. From that company have come so many brilliant dancers including Jerry Grimes and dancers in my company that I’m bringing to L A, Elizabeth Burke and Luke Hickey. We’re so lucky to have Gene, have so much care and passion for the form and he would learn alongside us. I say all that to say it was the music of tap dance and the feeling of making the music is what I think, empowered and impassioned me and it just became my identity. The only thing I cared to do is be a tap dancer and to me it didn’t matter whether I ever did it as a professional. At the time there wasn’t a huge pathway for young people to be a professional tap dancer. I just knew I would always tap dance, whether I did it in the closet or around the stage, it was who I was from a really young age. When I create, it’s about the music all day. Gene talks about chat dance, the physical form. He always says the form follows the function. The look of the dance is because I wanted to make that scrape with the outside of my foot. I wanted a low tone, so I had to do a tone off, so the actual physical dance follows your compositional voice and that’s a musical voice. And it’s thrilling, I feel like we have the best kept secret in the world. There’s nothing that feels better than making music as movement.

Leah: Michelle, a lot of people you have mentioned, Buster Brown, Diane Walker, Prince Spencer, Jimmy Slide and they often dance with no music, totally a cappella. The music is only the sounds they make with their feet. Talk about the creative process and music. Do you create music for your work or does someone else create original compositions to fit what you create?

Michelle: I appreciate this question because one of the things we’re bringing to the Ford is the first full evening work I ever made and it’s almost entirely acappella. That’s it.

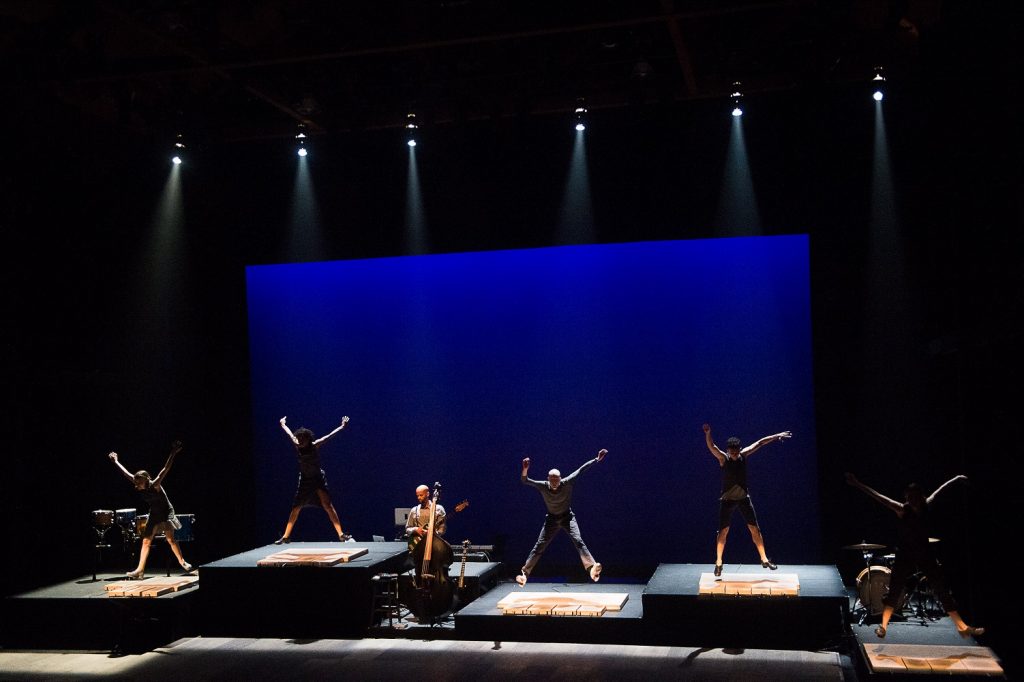

We’re, we’re doing a truncated version. The work is called SOUNDspace. And so, when given the opportunity to make a full evening for the first time the show is acappella entirely for the first 45 minutes. Then we introduce one single instrument and it’s a double bass. Part of the reason was it was a site-specific work created for Saint Mark’s Church in the Bowery in New York City. The acoustics of this church were so incredible. I just thought, what a great downtown space to help an audience, especially because the folks that go to that space to see performances are mostly postmodern dance community and I feeI can invite these people to understand this form in this space. We started the whole work completely in the dark just listening for the first handful of minutes. In fact, in the original version of that work I featured Dormeisha and she walked into the space and around the upper balcony and down the stairs in hard sole shoes just so you could hear the way the sound resonated in the space. Then the very first work we did was a tribute to Jimmy Slide in socks. You can hear the footfall of a sock in that space and its sound fills the room with a base tone. Then we moved into leather sole shoes and then finally, we actually made wooden taps to dance in that space because they wouldn’t let us use metal taps on the floor. But that’s another story. When thinking about what to bring to the Ford, because I know the Ford, it’s known for being a music presenting venue and it has incredible sound, I thought, we have to do “Sound Space.” Most of that work is acappella. It is still some of my favorite work that I have ever created. Even now.

Leah: Going back to my original question, what music or musician is moving you now and why?” What role does music play in your creative process?

Michelle: Of course, I’ve been collaborating with Toshi Reagon and my incredible band and vocalist, Aaron Marcellus with my brother who loves to compose on piano with Greg Richardson, who became our musical director. I have these, these musicians that I’ve been so lucky to work with. And one of the reasons it was really powerful to work with them is that they would collaborate with me and with tap dance as a compositional voice in the conversation with the music. Those are the kinds of musicians that I seek to work with. Because everything that lives in our jazz legacy, you know, deep swing to blues, which really inspires me deeply, to experimental music to the funk, which of course, our generation will never escape. I was talking about that before; I can’t escape it when I’m by myself improvising. I always find myself into a funk pocket. I could be swinging and eventually I’ll get there because I was so deeply influenced by Gregory and then Savion, you know, and also, it’s so funky. I can’t help myself. Even in being inspired by music, which I am endlessly. I can hear a piece of music and immediately think of a percussive line to sit with it. The first half, we’re featuring some great vocalists, and I love the idea of vocals and taps because there’s so much space between the two in a sonic, like there’s so much sonic space between the two. There’s room for both and often the way, when we have to do a sound check, mix tap dance into live music. We have to find a way to carve out the voice of tap dance, against the snare or against certain elements of a drum kit. I love working with live drummers. I really want the Ford to be filled with the sound of tap dance percussion.

Leah: Musician who moves you?

Michelle: Oh my gosh. That is a layered answer of course. In the first half of the show at The Ford I’m featuring two women’s voices and there’s something about the sound. I think we all feel this way. There are a million brilliant singers out there, brilliant vocalists and you can tell when someone is offering a really deep truth, both of their own and also that they’re a vessel for something much older. Much deeper than just one’s mortal life. Brene Ali, who is also a brilliant tap dancer, Allie Bradley, Alexandria Bradley, but she goes by Brene Alle. and she’s from Flint, Michigan. I met her as a teenager at the Chicago Human Rhythm Project but we also went to Saint Louis together. We were in Ted Levy’s residency. That’s where we met as teenagers, that voice…and also, she’s a brilliant tap dance soloist and choreographer, but her voice brings something really kind of ancient into the space… another woman who is also rooted in tap dance and is a body percussionist. Actually, both Ali and Brene and this woman Penny Penelope Vent, they were both in STOMP. We never overlapped. I was in that show like just a few years before each of them, but we all have a deep percussive language in us and both Brene and Penelope bring something from before their time into the space vocally. And that’s how the show at the Ford’s going to start. It’s going to start with the two of them. Right now, I’m just so charged by their voices and they both do, they both work in like live looping. But they also bring something so unique to the space and into each other and we all will have the opportunity to work together for the first time, Penelope Brune and then Josette and Jillian, who I’m also featuring. We just came back from Mexico exploring this work, something I’ve been working on with Penny, some other things I’ve been working on with Jillian and then creating some new ideas with Josette, Jillian and Berne. All of us coming together, I think it was really special then. We literally just decided that too. I had a completely different rep laid out for the beginning, but this is it to me. I’m so inspired by it in this present moment that we have to bring it to the Ford.

Leah: You mentioned Josette Wiggans and earlier you mentioned Joseph Wiggans. I’ve known them since they were kids at Paul and Arlene Kennedy’s studio. Please give them a hug from me. My youngest daughter took classes with Paul and Arlene.

Michelle: Josette and Joseph are two of my favorite dancers on the whole planet. That’s so cool. The Kennedys, I mean that’s a legacy that is just so important. It’s so important in our community, their legacy and the dancers that continue to carry it. I mean it’s something that I have to talk about. The way that folks embody their teachers and mentors legacy. I can imagine Paul and Arlene and also Mildred, now that I know more about her from Diane Walker. I can imagine they’re so proud.

Leah: You are so right about that. I went to New York for my birthday and saw Jelly’s Last Jam, Encore production and Dormeisha’s tap choreography was phenomenal. She and Edgar Godineaux knocked it out of the park. The choreography moved the story along and it was seamless. It was fabulous!

Michelle: I saw the invited dress which was great. The energy there, because it’s everyone’s friends and so many folks from the tap community, was unbelievable. Their choices reflected a time period and then also was cutting edge and Alaman (Diadhiou), who I have adored since he was a kid, was brilliant.

Leah: I have a few more questions for you. You founded your company in 2011. Why?

Michelle: it’s interesting. I barely even knew that I was founding a company. I just knew that something was happening. I was really excited to make work and because there were so many brilliant individual dancers in New York, both my peers and some of my students and everyone in between. I couldn’t help it. I just thought, oh gosh, I had visions for people in their own styles and of course, also had choreographic ideas and I thought, we can’t not do something. It felt like an unprecedented time in tap dance. There were unbelievable dancers and there still are but at the time, there were so many incredible dancers in New York City and each unique unto themselves. The very first time I created work, I called it Dorrance Dance because I had a print deadline and couldn’t come up with a creative name. And then it, it just continued. But I mean, that literally had almost everyone we’ve talked about in it. Josette (Wiggans) was still on the West coast, but Joseph (Wiggans) was in that first performance, Chloe (Arnold) was in that first performance, Cartier Williams, Savion’s protege was in that first performance along with some of my company members that are still with me, Elizabeth Burke, my dance captain who literally had just moved to New York City. She was 18 years old, she just moved there from North Carolina. She was killing it right alongside Joseph and Chloe, my dear friend Nicholas Young, who’s brilliant, and also a drummer, percussionist, tap dancer. It was nuts. It was really more that I was inspired by the people around me and felt the energy to do something. I also broke my foot, and I was in Stomp at the time, but I was doing something at Broadway Dance Center of course late night for free. They wanted to make some video, and I said yeah, I’ll do it. And the New York City Tap Festival was happening. A million things were happening at once. And in a late rehearsal, I broke my foot, and I was 29 and about to turn 30. I was just like, whoa, I’m not gonna have this energy in this body forever. I really need to pursue these ideas that I have before it’s too late is what I thought in my head. Now I’m in my forties and I still gotta do this. It felt really pressing for a number of reasons, the broken foot and also just the energy of the dancers of my generation and younger in New York City at that time, I couldn’t help it.

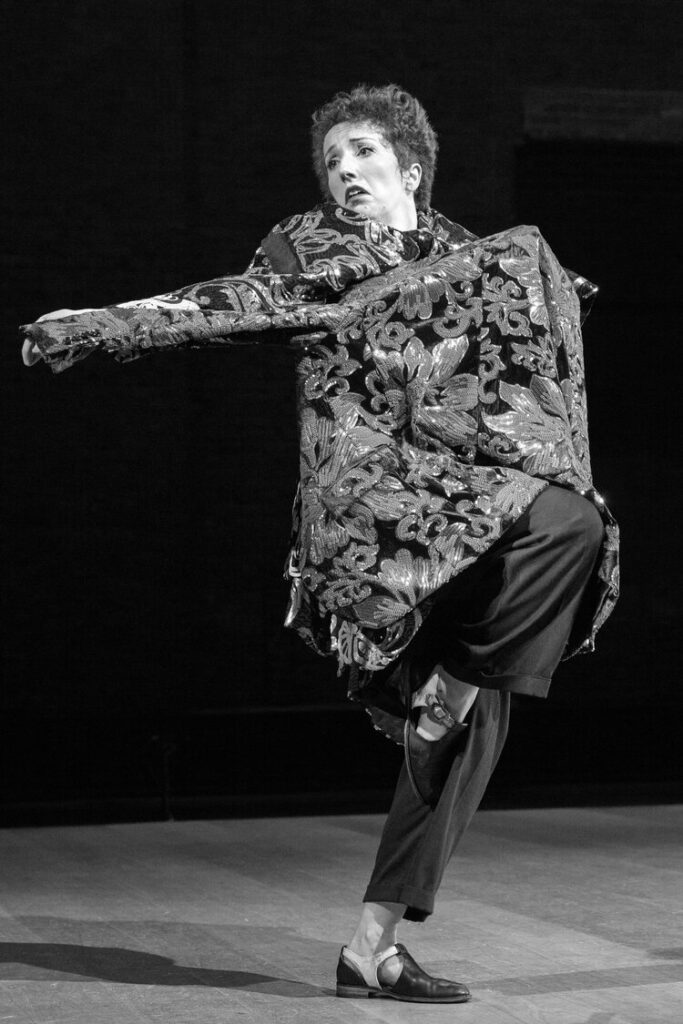

Dorrance Dance – Nicholas Van Young & Michelle Dorrance setting up the set – Photo by Matthew Murphy

Leah: What does this quote mean to you? “A sonic distillation of a blistering American past and its perilous present with a transcendent strength of spirit woven through.” Washington Post. This quote is on your website. When I read the quote, I remembered an event from my past. While in rehearsal for Tap Dance Kid I remember Danny Daniels saying to the young man representing Bill “Bojangles” Robinson, “ Why are you being so serious? This is not Martha Graham, bare feet and suffering, this is tap dancing.” I think you’re somewhere in the middle. What does this quote mean to you?

Michelle: Interesting. It’s really important, about like simultaneously trying to acknowledge that we’re all carrying really like hundreds of years of history in the vocabulary that we have been so lucky to be passed down to like that. We get to carry this tradition and carry so many individual voices and innovators ideas. We carry that and, this is the generation, me, Chloe’s generation and others, we were so lucky to actually learn from the folks, some of them that literally invented some of these ideas, and or they learned from the folks that invented and innovated these ideas. So, you know, if it was that we, we didn’t learn directly from John Bubbles. We learned from folks that worked with John Bubbles. We didn’t learn directly from Bill Bojangles Robinson, but we learned from folks that honored his approach to the buck and wing. And that I can’t, I will never wanna abandon that. I’m not trying to throw shade or call anyone out. I know that folks wanna free themselves to be, to have a voice of individual expression that feels fresh or feels new. Nothing is new. What we’re doing is such a deep tradition that folks that aren’t practitioners might think an idea is new, right? What is really interesting, I think about tap dance in the present day. This is our life, and this is, this is our passion, this is our community, this is who we are and also have been charged by our elders to hold on to elements of this. There’s no shaking that but the deeper you lean into it, the more I think you can find personal innovation. I feel like I can uniquely hold a space of being deeply historical and also deeply experimental. I believe it’s a place where risks can be taken. And I also believe that one of the things that we are now free to do without the former oppression of the art form. The art form can have a real depth of emotional expression, that lives very much inside of tap dance technique and that we don’t have to divorce ourselves like we don’t have to be barefoot, Martha Graham dancers to be emotional, that we are deeply emotional as percussive dancers that we’re deeply emotional while holding on to this incredible tradition and really sophisticated form. I feel like that’s honestly the most remarkable way to honor top dance. It’s to show its possibility and also echo everything it has been if that makes sense. I hope that people can be invited to understand tap dance and its history and also see its possibility. I think that folks can often marginalize tap dance into a really narrow space. It has such depth and I only hope that we can help invite folks to understand.

Leah: I think what Savion did in Noise Funk , having a counter rolling of lynchings and seeing tap through a historical perspective was extremely powerful and innovative.

Michelle: That was pretty profound. Unbelievable. It was unbelievable. That was pretty, that was pretty profound.

Leah: Tell me about your mentor, Gene Medler. When I read about him, he was described as a Yoda. You speak about him with such respect and love. What was his greatest contribution to you as an artist and how do you pay homage to him?

Michelle: When I was 13 years old, he took us to the second ever Saint Louis Tap Festival. And we met Fayard and Harold (Nicholas) and Buster Brown and Maceo Anderson and Prince Spencer of the four Stepp Brothers. We met these folks and immediately understood the legacy. We were inspired by every single person. Every person had an individual voice and stylistic expression, and they only encouraged us to be ourselves. It’s where we met Diane Walker and actually Yvette Glover, Savion’s mother, who really took us under her wing. Diane has continued to be a mentor to the company, to Gene and to all of us. Diane is the reason I think our generation has such a deep relationship with so many. Those that we were spending time with but also the folks that we never would have met if it weren’t for her. I think Gene empowered us to lead ourselves and each other. This is, both inside of the youth company, North Carolina Youth Tap Ensemble (NCYTE) but also just in class. He asked a lot of questions and encouraged us to guide us like he knew what he wanted. Of course, this is like the kind of teacher that has a method that lets you lead the ideas. He’s after something, but he’s asking for you to come up with the answer. He would lead us with questions. He was invested in our thinking, not just lecturing us with his, he would share endlessly. He was so generous as a teacher, educator, mentor, human. I would say there are a few things that he said to me from a very young age. He talked to me like I was an adult. He put me in a class with teenagers when I was nine years old and he would speak to me like I was 18 and he felt like my friend, but also like a second father. He had a way of being so human with us as young people. He believed in that radical notion of leading us in a way that made us responsible for the outcome.

Let’s say we learned some rep. We learned rep from Savion. We learned rep from Barbara Duffy. We learned rep from Ted Levy. We would be responsible for holding on to it and he would ask us now, what did this person say about this section? We’d have to come up with what they wanted related to sound and lighting on our feet. We needed accents here. He’d asked us to come up with this. He took classes with us with Henry LeTang. He’d be with us in class and then for a storytelling session with the Nicholas brothers or class with Diane Walker. He was deeply invested in sharing the history. We did lecture demonstrations for kids. All of these things swirl into the tap dancers and community members that, he knew, and I knew. I guess he dreamed we would be tap dancers.

I think one of the most important things that Gene gifted us was to have a beginner’s mind, to stay serious. We watched him, he never stopped learning, he never stopped. He would learn maybe a new idea, whether it was a teaching idea, or a technical idea and he’d immediately bring it into the classroom. Watching him learn even as an educator and also the generosity and humility with which he offered everything. He was a part of passing the legacy on and he inspired and instilled in us to be that… be a part of passing on the traditions. We’re all vessels for this incredible thing that we’re very lucky to be a part of. “Stay whimsical” is another thing that he would say. “Find the joy and curiosity” . I think the edges of what we do exists in his spirit and what he would invite us to do.

He also encouraged us to improvise so young. He had a way of just giving us a one liner and it would echo. Jimmy Slide was also capable of that but he’d give us a one liner and you’d think about it for years, and he’d always remind us literally. I say this all the time, but it’s so important. Just dance to express not to impress. As a young person when you’re learning so much, especially when we were coming up, the new ideas and how fast you could dance. I think this is any kid learning anything you just kind of wanna push. He would just remind us when we’re improvising, stay musical, be expressive. It’s not about showing off. I think to be rooted in that part of the form is an endless gift. I know that was a long answer, but he’s taught us so many things and continues to and continues to remind us. He has Parkinson’s now and, and can’t demonstrate anymore, but he can sit there and say, “not quite.” I’ll be doing something simple, like living in a flat phrase and he’ll say, “ almost, drop your weight right there. He still has such a care for the refined details of things.

Leah: Partnerships and collaboration are super important to you. That is very, very clear. How do you choose who you collaborate with and for whom you will choreograph?

Michelle: It doesn’t even feel like a choice. It just feels like I don’t think. I go with my gut. I am present and I guess it’s a choice, but it feels like it comes from a deep or subconscious place often from the way life is unfolding. I listen to what’s happening in an encounter in the present day. I’ll tell you the story of how I got to work with Toshi Regan. First of all, I was a huge fan of her music since I moved to New York City. Two weeks after I moved to New York City, I saw Toshi perform live, and I was going to actually see the person she was opening for. I almost left right after her opening because I was so moved. I wanted to talk to my friends about it and we almost skipped the guy that we went to see. We didn’t and I won’t name his name because I don’t want him to feel offended.

I was so deeply moved by Toshi and then literally any club that I could get into because I wasn’t yet 21 I would go see her. I never, in a million years, thought I would get to work with her. She just inspired me so much musically. As a human, I mean, she’s a prophet and inspired us into protest, inspired us into action but also just her music has such a depth and truth. She’s just so funky too. I mean, she’s everything I would want music to be. I can’t believe that was 20 years later or maybe a little less, I had the opportunity to meet her through a friend that was selling merchandise for another artist. I mean, just like the craziest, confluence of things we met. She said, “Oh, I think I’ve heard of you,” I’m not sure what she said but she something encouraging. Even if she didn’t know who the hell I was.

I guess it was on her mind and she created a show called Celebrate The Great Women of Blues and Jazz and she reached out and said, I believe we need a tap dancer inside of this work. She had an all-female big band. She had all these different vocalists representing the women that changed the game through history and that I was invited to tap dance on a show that I would have spent $100 to see. I mean even a $1000, if I’d ever had the money. But this is a while ago. I couldn’t believe that I was invited into that space. I just thought, how could we not create an entire show with tap dance with Toshi’s perspective on music? That’s when I said Toshi, if I could raise a bunch of money, could we ever work on a show together? She said, oh, you don’t even have to raise a bunch of money to do that, let’s do it. I realized if I have the opportunity to work with her, my two collaborators need to be Derek (Grant) and Dorms (Dormeisha Sumbry-Edwards). It’s very much because of the way she honors American musical legacy and the way Dere and Domes honored tap dance legacy that I thought that this is the only possibility here.

That’s how the blues project started. I tell that story to say, I think when we’re working as artists that aim to reflect what’s happening now or what’s important now, culturally, we can invite folks to think either bigger or, you know, differently that we can change the frequency literally… Especially now. I’ve been talking about this with a lot of friends lately. There’s so much division and hatred throughout the world, but especially in our country. And how do we address that? And how do we ask folks to address it and to help create change? All we can do is trust our gut with the folks that we need to stand beside us and work with us right now. That’s sort of how I’ve led myself into collaborative work in the past. What is resonant right now? And what if we have the opportunity and the gift to be able to put things in front of folks or be in a room with folks and help, you know, to feel something together. What do we wanna feel? What will take us forward as people, as change makers, as caretakers. That was a really long answer.

Leah: Yes, but your words matter so much…especially now.

Michelle: I’d really like to have coffee and talk to you. I’m here for the call back whenever you’re ready!!

Dorrance Dance appears at The Ford on Friday, September 6, 2024 at 8:00 pm. For more information and to purchase tickets, please visit their website.

To learn more about Dorrance Dance, please visit their website.

Written by Leah Bass-Baylis for LA Dance Chronicle.

Featured image: Michelle Dorrance – Photo courtesy of the artist.