The coveted Pacific Northwest Ballet streamed three ballets for an audience of online fans on October 6th through the 9th. One of the pieces was a performance of Carl Orff’s tour de force, the brilliant Carmina Burana. Founding Artistic Director, Kent Stowell attempted to bring this 70 minute ballet to life with the Pacific Northwest Ballet Company, the PNB Orchestra, conducted by Emil de Cou, the Pacific Lutheran University Choral Union along with three soloists; Soprano – Maria Mannisto, Tenor – David Hendrix and Baritone – Aaron Agulay.

Carl Orff’s cantata for Orchestra, chorus, and vocal soloists originally premiered in 1937 in Frankfurt, Germany after it was plucked from 13th century Latin and Medieval manuscripts discovered in a Bavarian Monastery. The manuscripts were presumed to be attributed to the goliards (young clergy scholars and students in Western Europe who wrote satirical Latin poetry in the 10th to 13th century.) The songs and tales are from Medieval life with its religious verses, social satires, ballads and bawdy drinking tunes.

Orff selected 24 songs arranging them into a prologue and epilogue (O Fortuna) along with three segments, Primo Vere (In Early Spring) presenting youthful, energetic dances; In Taberna (In the Tavern) evoking feasting and debauchery; and courtship and romantic love in Cour d’Amours (Court of Love). All is characterized in simple melodies, harmonies and heavy rhythmic percussion giving the piece a primal character, comparing the innocent, sacred, and profane of life.

Carmina Burana’s dynamic opening strains of “O Fortuna” with the revolving golden Wheel of Fortune, prominent in the Scenic Design by Ming Cho Lee, dominates the space. It symbolizes the metaphysics and randomness of triumph and disaster. The singers shadow the mammoth disc at the back of the stage area and introduce the evening with the exciting vocal prologue.

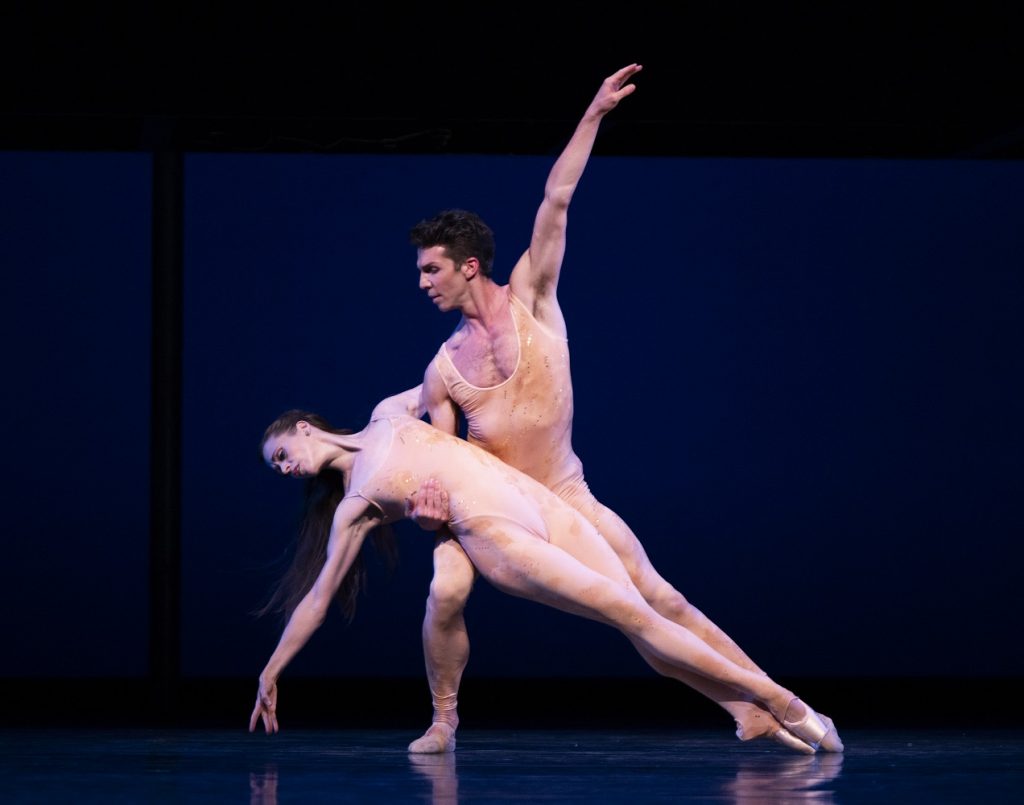

Pacific Northwest Ballet principal dancers Lesley Rausch and Lucien Postlewaite in Kent Stowell’s “Carmina Burana” – Photo © Angela Sterling

Dancers are supine on stage… moving into numerical patterns of pairs, groups of sixes and full dozen. They fill the stage patterning and re-patterning. Stowell’s interpretations were based on the numerological patterns of 12. The 12 scantily costumed dancers move in concentric circles that introduce the piece and trade places on the low lit floor.

Soon there is a transition of a lowly monk crossing the space as if in a dream. His imaginings are manifested by the glistening dance couples taking stage in numerous pas de deux with sensuous nude body suits. The muted costumes by the inimitable Theoni V. Aldred along with Larae Teige Hascall are the essence of the body beautiful in this 13th century fare. Later the groups move on to earth colored vests, dirndl skirts, and full blousy shirts. This, in contrast, highlights the fiery crimson costume worn by Elle Macy, a sensuous Gypsy woman in the piece.

Finally we ready ourselves for the chilling dynamic dance to begin. With regret, our expectation ran away with us, noting the numerous past spectacular versions of this classic. For this writer, the production only lived up to the expectations of grandeur in terms of numbers, expertise and beauty of the dancers. However, the soul seemed to have been laundered out of it. It was, simply put, “pretty.” The grittiness and irreverence of the time, the poetry, and secret titillations were as muted as the costumes. The licentious debauchery, the scandalous story telling is as restrained as Mona Lisa, and certainly not representative of the songs and musical promises. Stowell’s dance designs make gorgeous pictures for Grand Ballet. Is that what Carmina Burana is…a Grand Ballet? This version represents little context that gives meat to the bones of this exciting music.

With few exceptions, this very grand ballet has little passion, nor willingness to be off balance. One exception is the wily sensuous and provocative Macy, who was powerful in her romp with her male consorts, Kyle Davis, Luther DeMyer, and James Kirby Rogers. Oddly included in this, was a stray monk, Aaron Agulay, with an exquisite baritone voice. Agulay managed to place himself in a starring role in front of the most interesting dance action of the piece. This may have been a directorial choice, but not the best one for the camera and audience when we finally thought we might have a hint of possible sensuality to watch. The audience needed to see, not just hear the fire. This was an unfortunate choice since Macy brought spunk to the otherwise un-examined terrain of Medieval life.

In Taberna Quando Sumus (When we are in the Tavern) is a time for celebration adding a bit of spice to what has come before. Inebriated peasant men celebrate while a young man staggers around drunk and starts a tug of war with two lines pulling first one side then another, reminiscent of Le Noce. The gypsy girl then surges forward, controlling and captivating the group, and using her feminine wiles, manages to handle the stumbling men. My hope was that we would see more of her, because of the flavor of her fearless and wild abandon.

In Cour D’Amours (Court of Love) the lyricism of the dancers with their formations, reels, contra dances, exchanging and flowing with and against each other, prepare for the pre-coitus wedding couples’ evening. The ever-stunning Lesley Rausch, always classic and exquisite and the excellent Lucien Postlewaite simply posed as lovers, without demonstrating any real chemistry. While her handmaidens ready her for… we’re hoping…something!…that something never came.

The to-be bride then appears as an apparition, dressed in white. A group of females surround her as she is bathed in light. The young suitor begins to move in. The crowd of dancers separate, and the couple is finally left alone. But they have little connection. He touches her hand… no reaction. With their foreplay, it’s surprisingly bereft of passion or connection. He puts his head on her shoulder…and the young bride looks away. If she was directed to do this, why? It simply manifests itself as empty vapid posing.

As the piece ends in celebration, we see plenty of grandeur but just like these lovers, we’re left with emptiness. The grandiose opulence and pretensions of this ballet are lost in this telling. It can be said to be beautiful but none-the-less, empty. My hope is that this piece will be reworked, with the intention and fire, bawdiness and fun that was its original intent.

To learn more about Pacific Northwest Ballet, please visit their website.

Written by Joanne DiVito for LA Dance Chronicle.

Featured image: Pacific Northwest Ballet company dancers with the PLU Choral Union in Kent Stowell’s Carmina Burana – Photo © Angela Sterling