The last time I was at Television City, I lined up on the hot sidewalk for hours before being corralled and marched into a bright studio for a live filming of So You Think You Can Dance. On the evening of June 5, 2025 for American Contemporary Ballet’s “The Euterpides and Serenade,” the scene was set very differently. The long benches that had held crowds of jewel-toned clad fans were empty, and instead of a bright studio with blasting pop music and flashing lights, I entered a subdued, softly lit environment with live piano music. Champagne was served for opening night reception, and while there were some first show jitters, I overall enjoyed the evening of dance presented.

The first work presented was the premiere of “The Euterpides,” choreographed by Lincoln Jones and with original music, created in collaboration with the conception of the ballet, by Alma Deutscher, who was present to conduct the live music. The ballet was well-paced, consisting of an opening section, solos for each dancer, a pas de deux, and a finale section. The work was based on the myth that if “a mortal is beloved enough by Euterpe, Muse of Music, she will send some of her many daughters to dance with him.”

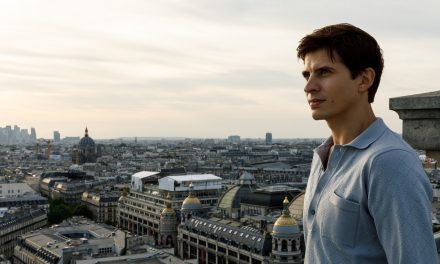

American Contemporary Ballet – Kristi Steckmann in “The Euterpides” choreography by Lincoln Jones – Photo by Anastasia Petukhova.

The group sections showed Jones’ Balanchine influence with the use of weaving pathways and evershifting arrangements of movement. The dancers moved well together in these opening and finale sections. In the program notes, Jones spoke about wanting to, like Balanchine, create visual music through dance, and overall this went well. There were moments in the finale where it appeared that two dancers were supposed to catch different layers of the music in contrast to each other, but it was not executed clearly enough, and the dancers looked not quite together and not quite clearly in contrast. The solos moved fine and each matched the music. Madeline Houk as Pneumē was particularly solid with beautiful, suspended balances in her choreography. The other daughters were portrayed by Victoria Manning, Kristin Steckman, Quincey Smith, and Annette Cherkasov. The dancing was technically proficient, though many of the dancers seemed tense during turns and I would have loved to see them take up more space and use their épaulement more dramatically.

American Contemporary Ballet – Madeline Houk and Mate Szentes in “The Euterpides” choreography by Lincoln Jones – Photo by Anastasia Petukhova.

The overall lighting was simple, featuring large pools of light that shifted color with each section. It made the space feel vast since we didn’t see the wings or back of the space. For one of the solos, the dancer seamlessly appeared out of the darkness in the back of the stage, and later, before the pas de deux between the Mortal, Szentes, and one of the daughters, Houk, a moving pool of light entered the space and connected with the larger pool before the dancers came together and interacted. However, either due to design or limitations of the space, there was not a lot of front lighting on the dancers’ faces. I wanted either more front lighting or for the dancers to look up and out more to catch the light that was there, as even with the intimate distance between the audience and the dancers, I didn’t feel their performance and energy projecting into the audience. Especially in the solos where the dancers couldn’t connect with each other onstage, the dancers could work more on projecting outward and connecting to the audience.

Between the two dance offerings, we enjoyed a musical interlude from Deutscher’s opera version of “Cinderella.” I can’t comment on the musical execution, though it sounded great to my untrained ear, but as a dancer, I did enjoy watching Deutscher’s movements as she conducted, and the way the sections of the string orchestra would sway together or how the strings of the bows would catch the light as they moved in the same broad strokes.

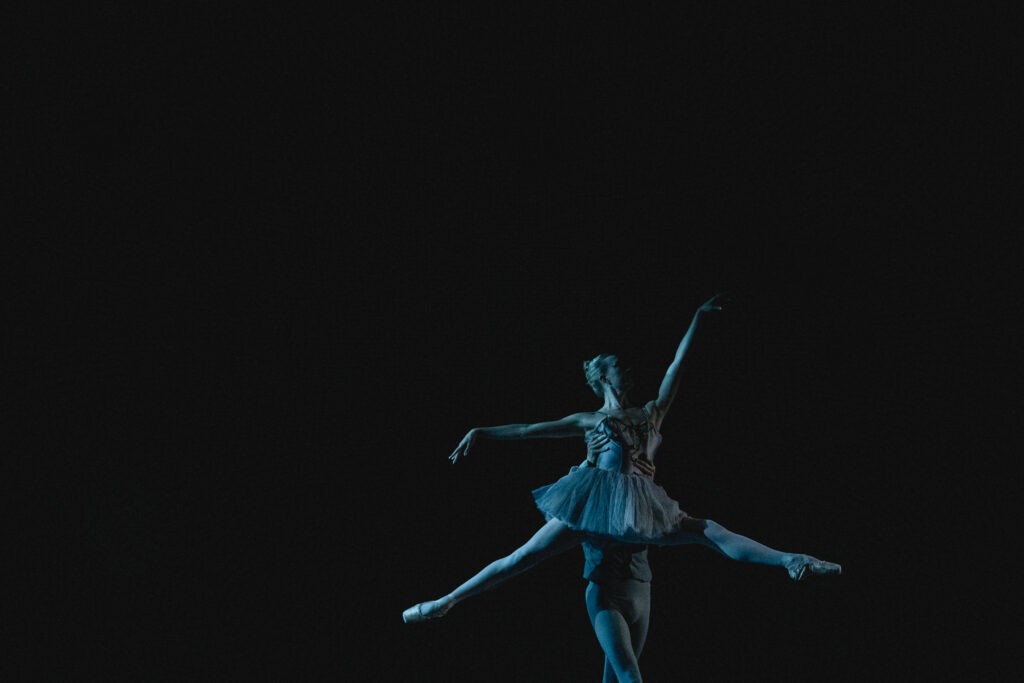

After an intermission, American Contemporary Ballet presented George Balanchine’s “Serenade,” staged by Zippora Karz. This ballet, originally presented in 1935, was Balanchine’s first ballet in America and is a choreographic masterpiece showing off the beginnings of his neoclassical ballet style, as well as his strong use of the corps de ballet, who were often relegated to lots of standing and posing in older ballets.

It felt like there were some opening night jitters that impacted the performance. At the start, the beauty is in the simplicity of the 17 dancers moving their arms or turning out their legs at the precise same moment, and the unison was not as tight as it needed to be here. As the dancers pointed their legs to the side and arched their backs, some had a beautiful soft shape with their heart reaching to the ceiling, while others bent so far back that it felt like a broken shape.

The stronger sections of the ballet were the more action-packed ones, and the dancers showed their technical strength in moments like the full cast menage of turns in a circle, as well as the arabesque chug sequence where they were immensely synchronized with their arm actions and quick hip flips to change from arabesque to a front leg. In simpler moments, the bends of the body and the reaches of the arms were not dramatic or yearning enough and things could feel stiff.

Annette Cherkasov, Madeline Houk, and Kate Huntington were the three female soloists, often known as Dark Angel, Waltz Girl, and Russian Girl. Huntington was particularly memorable as Russian Girl and showed off quick footwork, strong turns, and nuances of Balanchine’s style, like jutting of the hips.

American Contemporary Ballet – Annette Cherkasov George Balanchine’s “Serenade” – Photo by Anastasia Petukhova.

In the final section, the three lead women along with the male leads, danced by Maté Szentes and Joshua Brown, needed to bring more emotional projection to bring the simpler moments to life. Things were executed technically well, but the emotion between the lines of this so-called storyless ballet fell flat. Some moments, like when four of them spin together and burst apart or partnered attitude dips, needed more risk to match the intentional choice by Balanchine to have the female dancers have their hair down.

In one of the final moments of the section, the dramatic lift of Houk by three of the men onto one of their shoulders went awry at first but the dancers were able to try again and managed to finish strong with the statuesque last image of the ballet with Houk arched in the air, followed by seven dancers following on their toes in a matching backbend shape.

The overall ballet had ups and downs, more performance-related than technical, as the dancers did well with the execution of the choreography. Balanchine’s choreography calls for more moments of risk and this, along with more reach and energy, would bring the work to life even more. The costumes, made true to Barbara Karinska’s original design, feature light blue tulle with subtle yellow panels to represent where the legs are and accentuate their movement even under long skirts, and the live music was fantastic. With more performances taking place until June 28th, there is time for the piece to develop and come fully to life.

American Contemporary Ballet’s “The Euterpides and Serenade” continues through June 28 at Television City, 200 N. Fairfax Avenue, Stage 33, Los Angeles, CA. 90036.

For more information and to purchase tickets, please visit the American Contemporary Ballet’s website.

Written by Rachel Turner for LA Dance Chronicle.

Featured image: American Contemporary Ballet in George Balanchine’s “Serenade” – Photo by Anastasia Petukhova.