As anyone who has been following dance in Los Angeles knows, choreographers have been utilizing Zoom, Instagram and Facebook Live, streaming dances online to present their work to audiences who are quarantined at home. On Friday evening, October 2, 2020, Laurie Sefton was one of several choreographers who has returned to an old idea made popular in the 1950s, the drive-in, by presenting Breathe in the north parking lot of The Original Farmers Market in LA with an original music score by Bryan Curt Kostors performed live.

“Breathe” by Laurie Sefton – Dancers L to R Ellen Akashi, Ava Gordy, Camila Arana, Dominique McDougal, Leah Hamel – Photo by Denise Leitner

One of the first artists that I am aware of who made use of this idea was back in 2004 when New York based choreographer Noémie LaFrance who presented a performance with 10 dancers in a Lower East Side parking garage, with the audience sitting in their cars and turning on their headlights to provide lighting. This was, of course, before the Covid pandemic brought the world to a screeching halt.

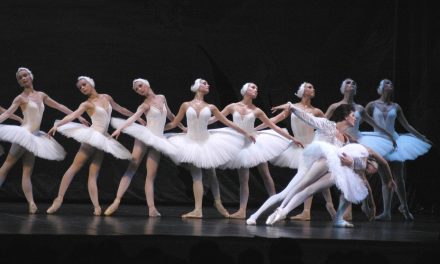

Back in May of this year Jacob Jonas, Artistic Director of Jacob Jonas/The Company, was the first to present a drive-in dance during the pandemic. The work was titled Parked and took place in an empty parking lot of the Santa Monica Airport. The occupants of the cars received a list of instructions about when to turn on their headlights and, rightly so, told them to wear masks. On October 9 & 10 the Westside Ballet will present Grace and Grit/Dance In the Time of Covid in the east parking lot of Santa Monica College. It will be a true drive-in movie event with the dances being on recorded.

This is a wonderful method to safely present live performance to audiences and I applaud these artists for their creative ingenuity. One of the difficulties of creating a dance on Zoom is that the performers are not in the same room and their movements are restricted to the small area within their homes. Sefton’s Breathe suffered from this restriction, and she was unable to clearly move past that cubicle, webinar visual that has become our new normal of staying connected.

As one drove into the parking lot, the driver was handed a page of instructions that told us we would be listening to live music transmitted through the car’s radio. “Please tune your radio to station 87.7 FM.” It read. There was a row of small lights lined up next to the curb of the parking lot behind the dancers. The instruction were that when those lights were red, the car lights should be off. When yellow, they should be on and when green, the headlights should be on high beam. This was how the dance was lit and how the music was heard.

In an interview with me, Sefton stated that Breathe “This whole piece is about the shortness of breath and that George Floyd was suffocated,” At a time when we all are thinking about breathing and wearing masks, Sefton said that she hears people say ‘just take a deep breath’ when talking about the difficulties of wearing masks. “And that is the most loaded word right now!”

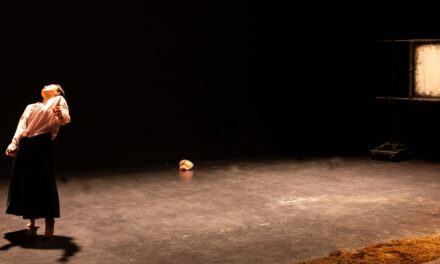

For the most part Sefton’s dancers were isolated from each other during the 28 plus minutes of Breathe, lined up in front of our cars. Wearing a variety of street clothes and masks, the dancers performed movement that appeared constricted and unable to expand outward beyond unseen borders. Throughout the work, this sense of isolation continued even when the dancers did actually move to a new section of the performance area or when two dancers actually made physical contact.

The dancers’ gestures reflected a difficulty to breathe when they wrapped their hands around their necks as if being choked or covered their mouths as if being forbidden to speak. At one point the dancers lined up close to the cars, but why? I never saw or felt a shift in attitude, nor did I feel confronted or threatened.

The work, she said, was also about protest and this was made clear at the end with the dancers putting on black t-shirts with white lettering that read Human, Free Spirit, Mr. Peanut is Female, Feminist, and In Art We Trust. The movement became larger and faster leading to some dancers lying on the ground as if injured or worse.

Kostors’ electronic score evoked tension and at times a driving force behind the dancers’ emotions. Sections had an underlying rhythmic beat that while seated in my car made me begin to feel uneasy. I am sure that this was intentional as it reflected Sefton’s vision of constriction.

Sefton’s ability to provide “normal” dance composition to Breathe, did not go unnoticed. There were sections with unison dancing, two separately choreographed duets working against with a male solo, and limited, but discernable movement patterns across the space. This was not an easy task to create while working with dancers on Zoom. It all had to happen within the Sefton’s imagination.

L to R Ellen Akashi, Ava Gordy in “Breathe” by Laurie Sefton – Photo by Roger Martin Holman for LA Dance Chronicle

Breathe was not one of Sefton’s best works, and, for me, she did not succeed in taking us out of the small, cubicle webinar feeling one experiences while watching dance on Zoom. I greatly appreciate that she took the risk to provide her audiences with a live dance performance. We are all eager to get back into the theater to experience live, in-person performances.

The performers in Breathe who not only danced well but who had to do so on concrete while wearing sneakers were Ellen Akashi, Camila Arana, Leah Hamel, Ava Gordy, Dominique McDougal, and Alejandro (Aleks) Perez. The Lighting Design was conceived by Dan Weingarten.

Written for LA Dance Chronicle by Jeff Slayton.

Featured image: Dancer Camila Arana, Composer/Musician Bryan Curt Kostors in Breathe, choreographed by Laurie Sefton – Photo by Rodger Martin Holman for LA Dance Chronicle