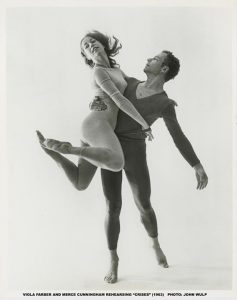

Born in Heidelberg, Germany and raised in Washington, D.C., Viola Farber was an original member of the Merce Cunningham Dance Company founded in 1952. She performed in the first performances of Cunningham classics Banjo, Dime A Dance, Minutiae, Suite For Five, Nocturnes, Summerspace, Antic Meet, Crises, Winterbranch, Aeon, Field Dances, Story, Cross Currents and Paired, and more. When she left in 1965, Viola Farber was one of only two soloists with the Cunningham company, the other being Carolyn Brown. She went on to become Artistic Director/Choreographer of the Viola Farber Dance Company (1970-1985) and to choreograph for soloists and modern dance companies around the world. She was the Artistic Director/Choreographer for Le Centre National de Danse d’Angers (CNDC) in France for three years (1981-1983), on the dance faculty at The Place in London (1984-1987), and from 1987 to 1998 she was the Chairperson of the Dance Department at Sarah Lawrence College in Bronxville, NY. Viola Farber was highly respected as a dancer, choreographer and a teacher. After her death, the French Minister of Culture announced that Viola Farber’s work was officially recognized by naming her to the Ordre des Arts et des Lettres (Order of Arts and Letters). For the French Government to award such an honor, a person must have “significantly contributed to the enrichment of the French cultural inheritance”. Within many dance circles of the United States, France and England, Viola Farber was a modern dance legend and/or icon. Because of our close professional and personal relationship, I will refer to her as Viola.

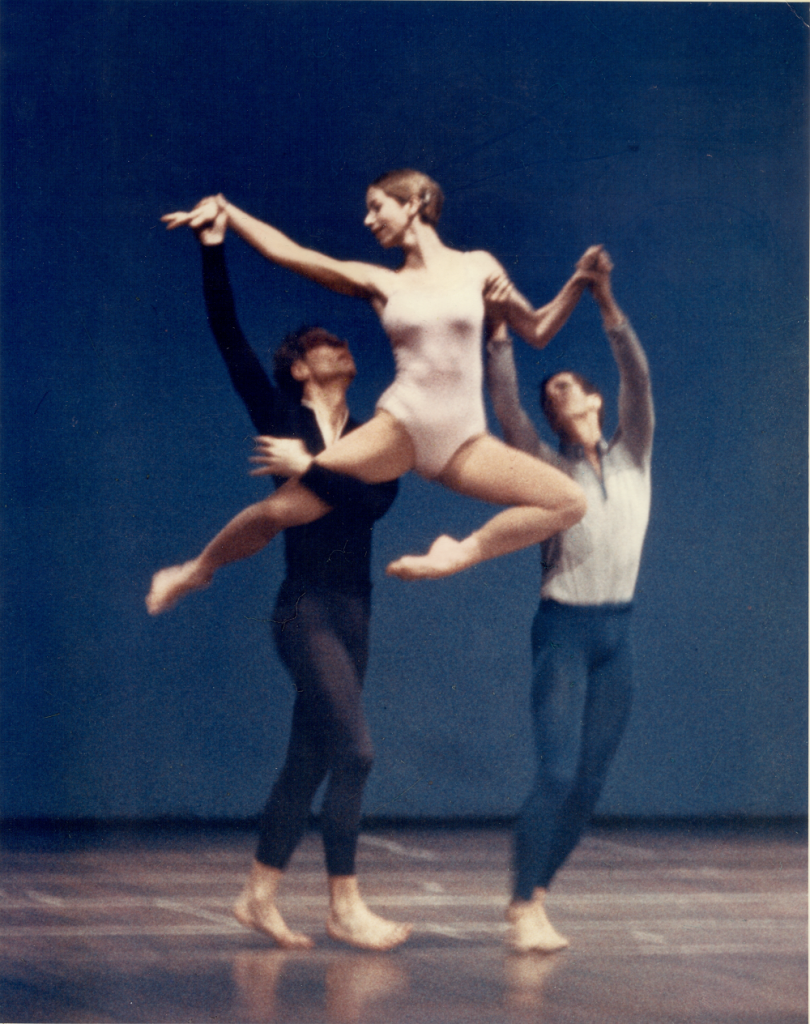

L to R Merce Cunningham, Viola Farber, Remy Charlip in Cunningham’s Septet (1953) – Photographer unknown

I first met Viola at Adelphi University where she was teaching part-time and I was in my first (and last) year as a dance major. During that academic year (1966-1967), I studied with Viola, Dan Wagoner, Don Redlich, Martha Myers, Bunty Kelly and Marie Adair; performing in Viola’s work Here They Come Again and in another work by choreographer Jack Moore. When Viola announced to our class that she would not be returning to Adelphi the next year, I followed her to New York and studied with her at the Merce Cunningham Dance Studio. That was August of 1967. Two months later Cunningham asked me to join his company and for the next three years I was on the road touring but continued to take Viola’s classes whenever possible.

During my last year with Cunningham, I also performed in the Viola Farber Dance Company’s debut concert at WBAI Radio Station along with Viola, Mirjam Berns, June Finch, Margaret Jenkins, Rosalind Newman, Andé Peck and Dan Wagoner. Because of how Viola constructed her dances and allowed us to make artistic choices while performing, I knew that that this was how I wanted to work. Her company was officially founded in the fall of 1969, and I left the Cunningham company in August of 1970 to join it. While leaving Cunningham may not have been the optimal career move, artistically I felt that I had no other choice; Viola’s movement style and choreography fit my body like a well made, custom tailored suit.

Jenkins, Newman and Wagoner went on to form their own companies. The dancers who replaced them and who formed the nucleus of the Farber company were Larry Clark, Willi Feuer, Anne Koren and Susan Matheke. Others that performed with the Farber company in New York included Jumay Chu, Michael Cichetti, Robert Foltz, Mary Good, Karen Levey, and Joёl Leucht. In 1981, Farber left New York to become the Director of the CNDC in Angers where she formed a new company with American dancers Cichetti, Foltz, Koren, Levey, and Leucht, along with French dancers Didier Deschamps, Chantal de Launay, Nadège McLeay, Mathilde Monnier, Sylvain Richard and Claire Verlet. Between 1969 and 1985, Viola created over 50 works for the Viola Farber Dance Company and over 40 for other companies, dance artists and dance institutions.

I performed in approximately 25 of those works, as well as in two dance films, Brazos River (1977, Music: David Tudor, Costumes: Robert Rauschenberg, Director: Dan Parr) and January (1985, Director: Kevin Crooks of Television South West Limited in London, Music: Gordon Jones, Costumes: Maria Liljefors,). Viola and I were married in the Garden Room at Judson Church in 1971, separated in 1978, and were divorced in 1980. Even after I moved to California following our separation, I continued to tour with her company whenever possible. Viola appeared as a guest artist in the 1978 debut concert of Jeff Slayton & Dancers (1978-1983), and we performed duets on two of the Long Beach Summer School of Dance faculty concerts (1982, 1984). Our last performance together was in a collaborative duet at the American Dance Festival in 1996. It had been several years since we had performed together, so we titled the dance It’s Been A While.

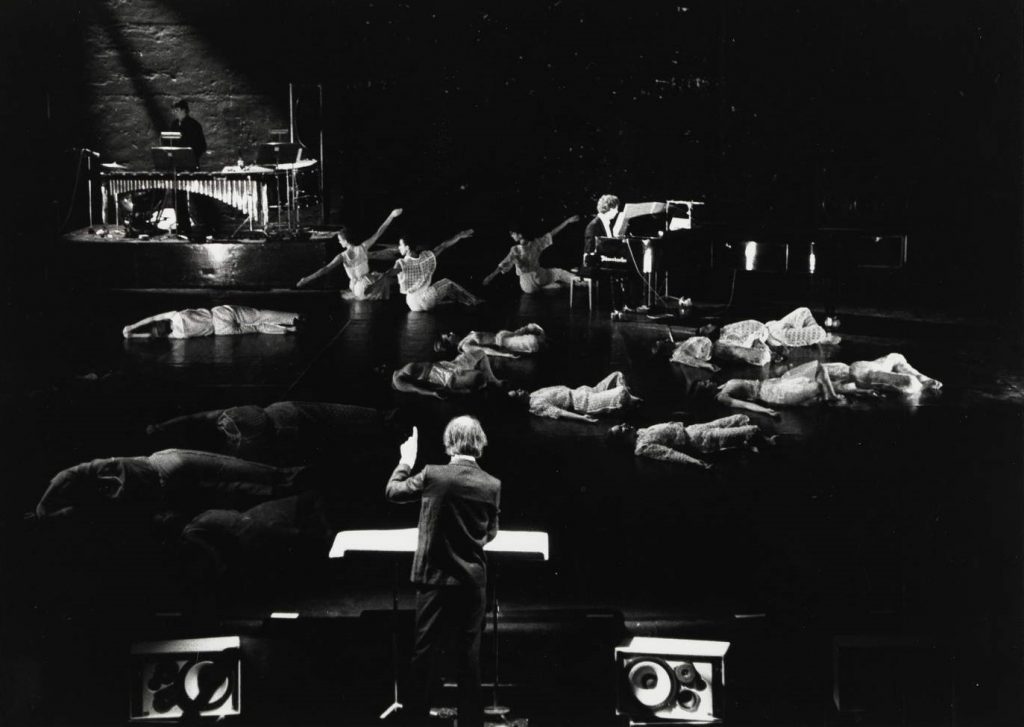

Dancing Viola’s work was both a joy and a challenge. Her technique was a fusion of Cicchetti Ballet, Cunningham technique and her own style of moving. She was trained to be a concert pianist before beginning to dance in college, and therefore even when we performed to electronic music, her work involved very complex and musical rhythms. Several of Viola’s early works for the company were performed in silence, forcing the dancers to closely listen to and watch each other. It was not long, however, before she began to choreograph to original electronic scores by renown composers David Tudor, Alvin Lucier, Alan Evans and others. She created dances to classical music by Poulenc, Beethoven, Mendelssohn and Villa-Lobos. She choreographed to two country and western songs for a duet with me called Doublewalk (1978) and in France her composers included Dominique Lofficial, Michel Portal, and Henri Texier.

Viola would occasionally teach a variation of her choreography in an advanced technique classes and rehearsals would then begin with such a phrase. She would rework it, and ask us to improvise on that phrase laying out very specific guidelines or rules. Generally, we had to go through the phrase in the order in which it was taught, but we were allowed to repeat movements, take them to the floor or into the air. We could make a movement turn when it wasn’t originally designed to turn or hold a position for a second or two along the way. During rehearsals, Viola would sometimes let these improves go on for ten minutes or more, allowing us to really explore the material. She once said that she could watch us do this all day. In performance, we would create duets or trios where none had been the night before. Viola generally had very definite time limits on such sections and she was not happy when we overstepped her boundaries. The bulk of her dances were completely set but they almost always included two or three structured improvisation sections. Because Viola allowed them to be part of her creative process, dancer turnover was very low in her company.

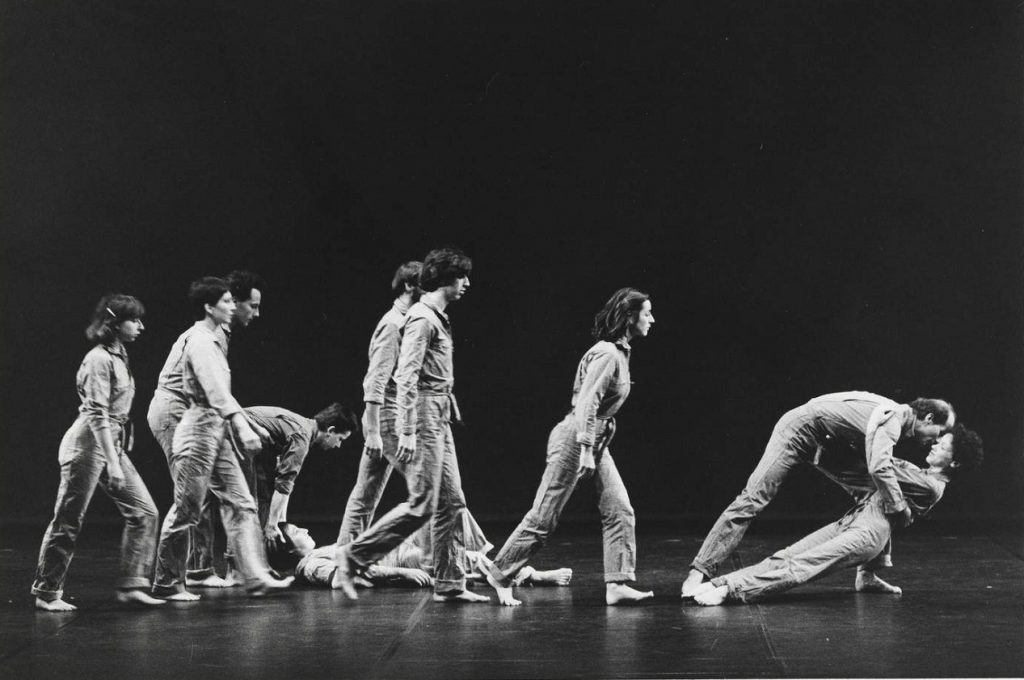

Viola Farber Dance Company in “Poor Eddie” (1972) – L to R: Jeff Slayton, Viola Farber, Andé Peck, Anne Koren – Photo by Mary Lucier.

Also, Viola did not pigeon hole or stereotype her dancers. She used their strengths, of course, but she was always creating material that challenged them as dancers and as artists. If a dancer was unable to accomplish a movement phrase right away, Viola allowed her/him the time to work on it, and she was always ready to help.

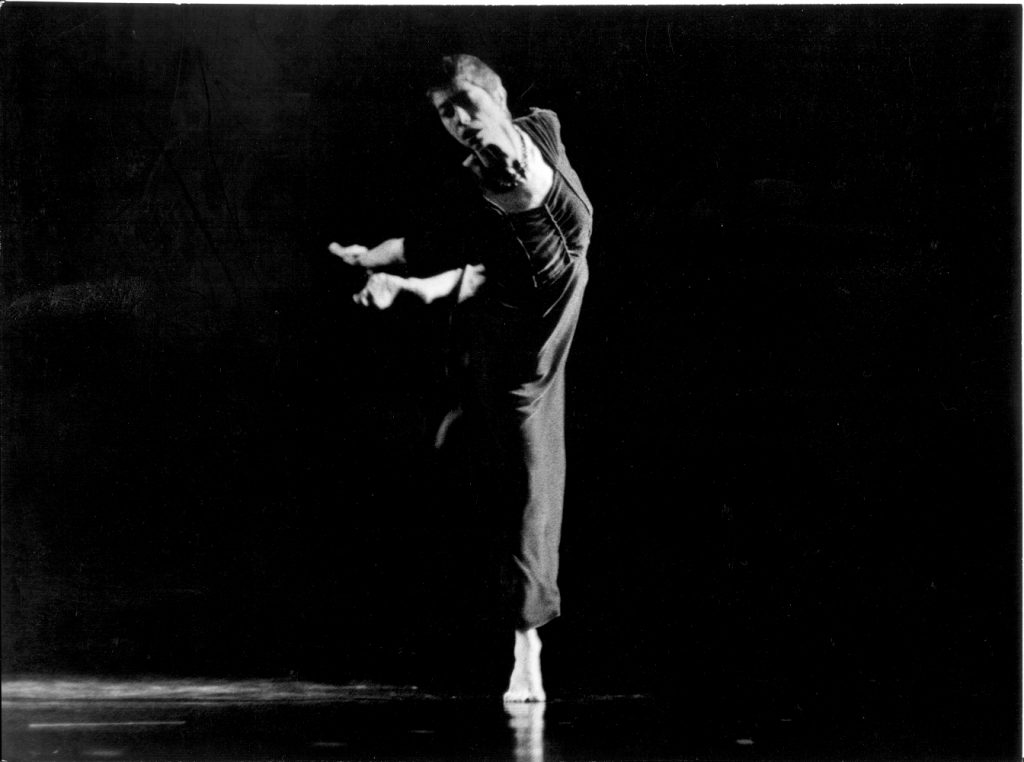

For her dance Survey (1971), not only were we challenged technically, but Viola also tested our endurance as athletes. Survey was 40 minutes in length and performed in total silence. It began with very slow and sustained arabesques that moved into a slow fouette on relevé and then balanced on half pointe. As the work progressed, the movement increased in speed and as we reached near exhaustion, we had to move our fastest. It was a work where everyone wanted to lie down afterwards and skip the curtain call. We felt too wiped out to stand there smiling while taking a bow. We always did, of course.

To demonstrate Viola’s dedication to her art and her expectations of her dance artists, I will relate a brief story that occurred during one rehearsal of Survey. The work had been in the company’s repertoire for just under a year. It was, as written above, a very difficult dance and one that we did not relish rehearsing. In short, it was a killer.

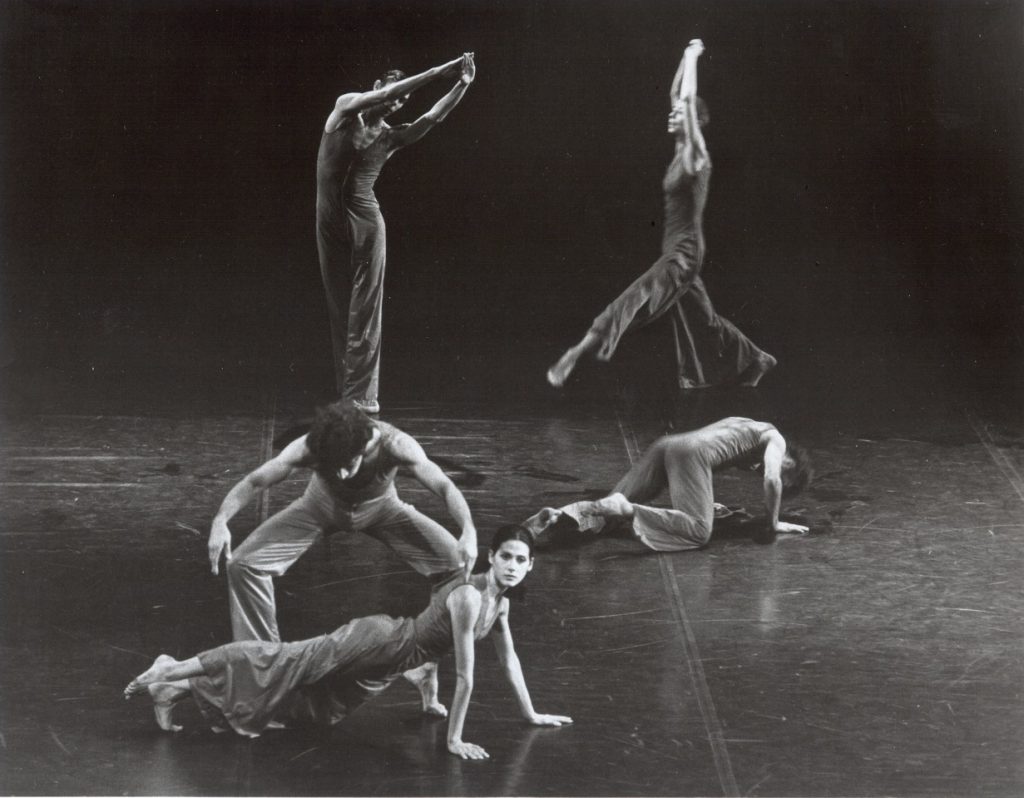

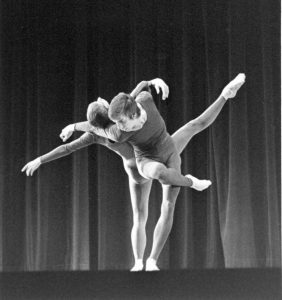

Viola Farber Dance Company in Willi I (1974) – Top row Jeff Slayton, Viola Farber – Bottom row Andé Peck, Anne Koren, Larry Clark – Photo by John Elbers

On this day at the end of the run of Survey, the company collapsed on the floor. Viola, who was not in the dance, sat on the floor in front of the mirrors. For a while she did not look at us or say a word. Finally, she lit a cigarette, inhaled deeply and stared at us as the swirls of smoke slowly escaped her mouth. We knew that Viola was not happy with what she had just witnessed.

“So, you call that dancing?” Viola said, her contained anger seething through every pore. “Do it again and dance it this time!”

We did and while we were anything but pleased, we knew that Viola was right. That second run-through almost destroyed us for the rest of the day but we realized that it was the work Viola had originally created. This was an experience that I would recall when rehearsing my own company and while teaching. Viola taught me that what is more important than one’s ego is the art of dancing!

As I have written, Viola’s work was wonderfully musical but for some, it was laced with violence. I never saw or understood what people were talking about because what I felt and later saw in her work was an intense energy and passion. Viola took her dancers to the far edges of endurance as people, as artists and as dancers. She tested their limits and, at times, their patience. She explored relationships, personalities and situations through non-narrative movement, or what was then termed “pure movement”. She would make dancers laugh and then suddenly rip them apart with an angry glare or a curt sentence; her look was often more deadly than her words. She did, however, always expect more from herself than she did anyone else.

I studied and danced with Viola for 30 years, but because she was someone who continued to investigate, absorb, change and grow, I never managed to learn all that she had to offer as an artist, a teacher or as a human being. For those of us who got to work with her, she was an unforgettable artist, a mentor and to some, a genius. At her memorial at the Joyce Theatre in 1999, Didier Deschamps expressed it well. “For those of us who were fortunate enough to study with her, Viola will live in our muscles forever!” Referring to the dancers at the CNDC, Deschamps added, “Viola, if you ever get bored up there, fly down and land in the arms of one of the dancers for a brief moment, and they will know what it is to feel light enough to soar.”

In one of his reviews for the Los Angeles Times, Lewis Segal called Viola and I “the Marge and Gower Champion of modern dance”. She was my dancing soul mate, and my closest, dearest friend.

There are a few videos of Viola’s work at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts and I am in the process of looking for permanent home for her archives. Viola was a stanch believer that dance is an ephemeral art and that it does not exist once the dancers cease to move. When she died on Christmas Eve 1998, there was not one recording or documentation of her work in her office or in her apartment, so I had to travel to New York City, Paris, Angers, and London to collect her professional materials. When she left for France in late 1980, Viola stored her company’s filing cabinet, with all its official papers and photographs, in the women’s dressing room of a friend’s dance studio. That is where it remained until I tracked it down in 1999.

It is true that Viola did not care if her work lived on after her death, but many others (myself included) feel that it must. I wrote The Prickly Rose: A Biography of Viola Farber (2006, AuthorHouse Publishing) because dance majors at California State University, Long Beach were always wanting information on her for their research papers. There was very little written about her other than her being mentioned in books about Cunningham. I have digitized her videos and collected photographs, business papers, articles and reviews of the Viola Farber Dance Company. Presently, everything is stored in our guest bedroom in Long Beach, CA.

Our dance pioneers, icons and legends must not be forgotten. We need more dance writers, historians and archivists to document and preserve their legacies in order to provide a pathway for future generations of dance artists.

To purchase The Prickly Rose: A Biography of Viola Farber, click here.

For more information on Jeff Slayton, click here.

To view the LA Dance Chronicle Calendar of Performances, click here.

Thank you for this! Valuable and enjoyable. My only contact of any sort with Viola was my friend Mary Lee Karlins who studied with her in NY. Mary Lee loved her and sort of feared her; she respected the hell out of her.