An enormous waning crescent moon appropriately blessed The Ford amphitheater on August 14 and 15, 2021, the evenings of Long Beach Opera’s double bill: Pierrot Lunaire (Moonstruck Pierrot) and Voices from the Killing Jar, setting the stage for an artistic menagerie of curated mayhem. Both pieces took an alternate look at women in opera, portraying strong leads that revised their place within literary lore, rather than reprise the genre’s more stereotypical roles as storyline casualties. Ate9 founder and artistic director Danielle Agami enhanced Pierrot Lunaire with a contemporary cabaret that at times competed, but mostly complemented Kiera Duffy’s Sprechstimme (an expressionist vocal technique between singing and speaking) in German. Voices from the Killing Jar did not feature any dancing, but Laurel Irene’s accompanying movement equally embedded her overall performance into the viewer’s mind.

Written by Arnold Schoenberg in 1912, Pierrot Lunaire is a melodrama consisting of 21 of the 50 poems in Albert Giraud’s book, Pierrot Lunaire: rondels bergamasques (Moonstruck Pierrot: bergamask rondels) about the titular character’s transition from an isolated moonlit world from which he observes sex and violence to the cruel real world within which the rest of the world resides. Rather than tell us his story himself, an atonal soprano (Duffy) became our Virgil through the dreamlike visions Ate9’s ensemble enacted to Wild Up’s orchestral music. True to the Sprechstimme style, Duffy wavered between high bubbling notes that dissipated into shrill lunacy, to rumbles that hung in the air like low yawns. Schoenberg’s lyrics evoked dark images full of whimsy and nightmares — “crystal flasks” and “sinister black moths,” “joys too long neglected” and “roses made of light” — which tingled in the mind.

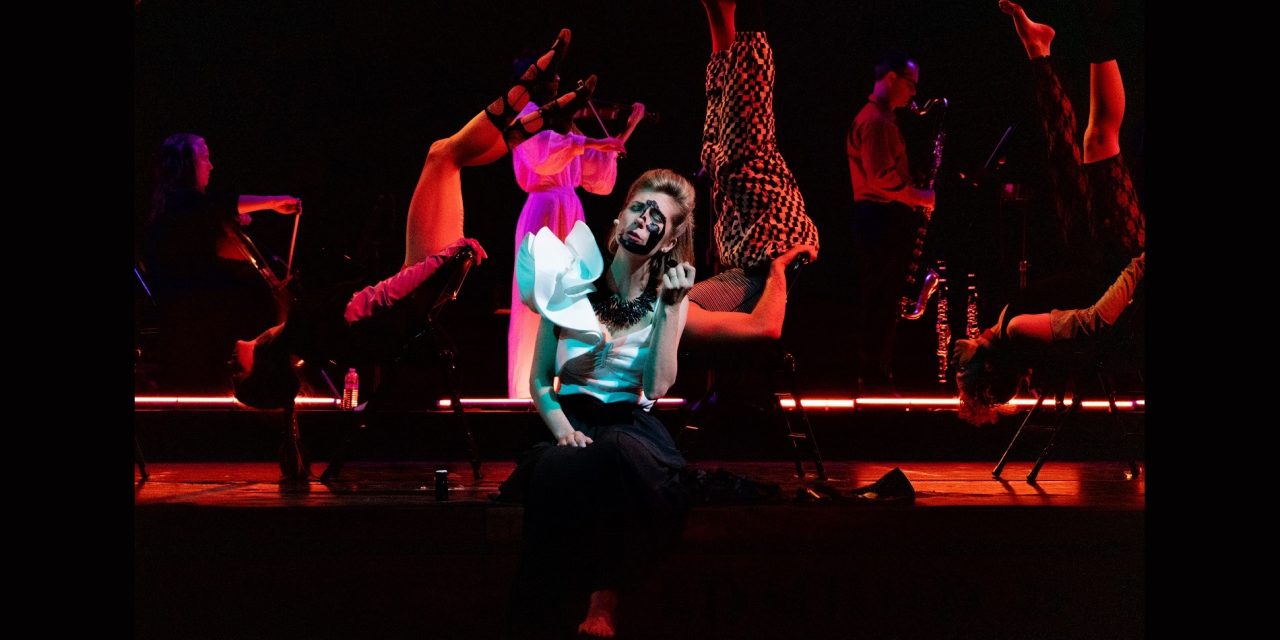

Ate9, which included Agami herself, Paige Amicon, Christopher Hahn, Cacia LaCount, Jordan Lovestrand, Bronte Mayo, Jobel Medina, Evan Sagadencky, and Santiago Villarreal, engulfed the stage like rising flames. Their bodies ebbed and flowed around the rotating rectangle upon which the chamber orchestra was perched. They led some of the 21 verses with silent gestures before the music began, while other sections assumed a reactionary approach to Duffy’s performance. Drifting between solo scenes and partner work, much of the ensemble’s routine remained focused on sensuality, particularly when it came to the floor work — crawling, sprawling, and intertwining with one another — that Agami’s work is known for. Duffy was often part of the choreography, daring the ensemble to reach out and touch her while contemplating “dark rivers” in “Columbine,” or sitting between two of the dancers, singing about shoving a drill “through the shining skull of Cassander” in “Cruel Pierrot.”

It is not uncommon for the choreography paired with Pierrot Lunaire to take on a more clownish, almost silly tone — a callback to the character’s roots in Commedia dell ’Arte. Agami’s decision to go with a more gothic and expressionistic cabaret rendition is a better marriage of the mostly sultry, yet still sometimes comic implications the text provides about the surreal landscape Pierrot traverses in his tale. Not strictly one style of dance, the movement contained elements of modern jigs with a contemporary flair. The more traditional signatures of cabaret, such as the incorporation of chairs as props, became evident during the second half of the performance.

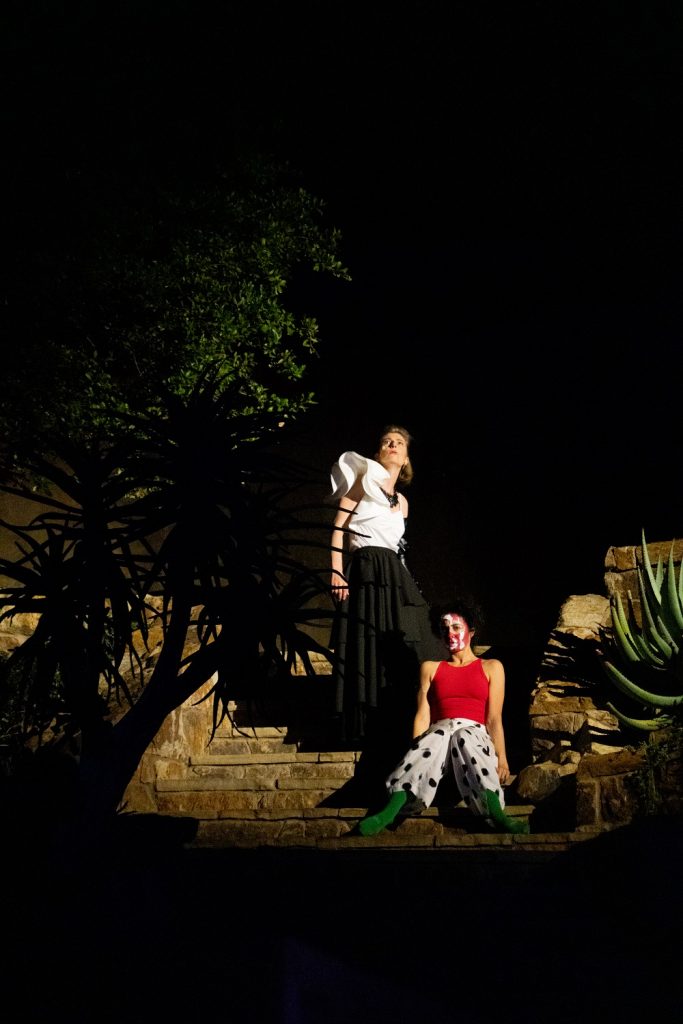

This diversity in motion was equally mirrored in the costumes. Michela Muratori’s design mixed white and dark face paint; included red accents in sharp accessories, such as single elbow-length gloves; and mismatched neon socks for an extra quirky touch. The colors were equally reflected in Pablo Santiago’s edgy lighting scape. One drawback to the dancing was a potential inability to fully absorb all of the nuances within the constantly shifting stage work while trying to read the translation of the German lyrics in a large overhead screen. Though it may not have been necessary to catch every word, the book did provide audiences with the narrative thread that connected the audio and visual elements together.

Kate Soper’s Voices from the Killing Jar (2012) graced the stage after a long intermission that allowed the necessary time to construct Tanya Orellana’s scenic design consisting of a curtained, square, wooden arch in the center of The Ford. Bright green–clad soprano Laurel Irene was a showstopper as the opera’s soloist. Throughout, she explored the roles of eight women typically overshadowed by their tragic backstories: May Kasahara (Haruki Murakami’s The Wind-Up Bird Chronicle), Isabel Archer (Henry James’s The Portrait of a Lady), Clytemnestra (the Mycenaean king Agamemnon’s wife in Greek mythology), Lucile Duplessis (the wife of French Revolutionary Camille Desmoulins), Emma Bovary (Gustave Flaubert’s Madame Bovary), Asta Solilja (Haldor Laxness’s Independent People), Lady Macduff (Shakespeare’s Macbeth), and Daisy Buchanan (F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby).

Carlos Mosquera’s soundscape magnified Irene’s power as it reverberated her voice throughout the amphitheater, lengthening bolder notes and expanding her already-astounding range. The addition of static radio noise and repetition heartened each character’s exclamations of autonomy and protest. Some segments were gentle, like Lady Macduff’s pre-execution lullaby. Others were loud and enraged like Emma Bovary’s shrieking howls of laughter upon experiencing a pivotal moment of madness during a night at the opera where she confronted skilled baritonist Abdiel Gonzalez and revealed the secret behind the emerald curtains.

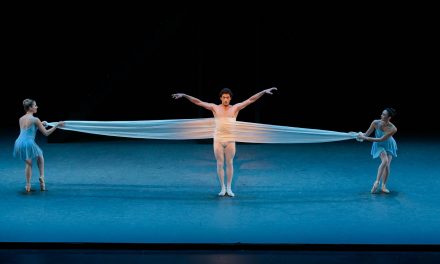

Though movement was not a major part of the piece, Irene’s sculptural stances and physicality augmented much of her singing through avant-garde techniques such as regurgitating vines and wrapping them around her neck in silhouette when playing Isabel Archer. Much like Agami, the floor became a common refuge for her to express her lamentations, inching toward the mysterious box center stage and curling her body against the ground as her characters indulged in fantasies of better days. Thanks to Zoe Aja Moore’s direction and Liz Toonkel’s execution of “illusions and magic” (a title that very aptly describes her contribution to the piece), the eight vignettes felt substantially separate yet connected throughout the 40-minute show’s run.

Despite expectations when hearing the word “opera,” dance and movement — in one form or another — played a significant role in uplifting Pierrot Lunaire and Voices from the Killing Jar. With a full century between them, both experimental productions paid homage to women and madness in a way that, for once, did not feel patronizing.

To visit the Long Beach Opera website, click HERE.

To visit The Ford website, click HERE.

Written by Lara J. Altunian for LA Dance Chronicle.

Featured image: Long Beach Opera – Keira Duffy and dancer in Pierrot Lunaire – Photo by Jordan Geiger