The audience at the Segerstrom Center for the Arts on Saturday night was a lively crowd; ballet enthusiasts antsy to find dance before them once more, applauding long and loud before the curtain even lifted. As Alonzo King hinted in our interview earlier this week, they were floored by truth spoken profoundly through movement – not just the technique they came to see, but also the hope that art gives.

The curtain went up on a lone Adji Cissoko for Grace, an excerpt from Pie Jesu (2020): she was captivating just standing still and incomparable in full flight. She painted the stage swiftly, graciously, each step she dances a generous offering to the viewer.

Babatunji, Ilaria Guerra, and Michael Montgomery joined her onstage, each with a quality that became distinctly universal throughout the evening: their arms were paintbrushes. At LINES, where the dancers are all of impressive height, their limbs don’t sprawl or loiter as you might expect. Their backs are delightfully articulate, directing sweeping and specific arm motions. They’re illustrating the work for you: it’s expansive and exquisite with every breath.

Madeline DeVries took the stage for Writing Ground, from Over My Head (2010), rooting herself in some of the most endearingly awkward, distinctly human choreography I’ve seen King build. I’ve admired DeVries since I was eight years old, peering through the studio window back home to watch her rehearse. Here, she transformed into an underdog even in my eyes, her movement brimming with so much personality you couldn’t help but cheer her on.

In an excerpt from The Radius of Convergence (2008), Babatunji, Lorris Eichinger, James Gowan, Alvaro Montelongo, and Montgomery alternated in boundless solos and simple, sweet unison. Montgomery was breath incarnate, each of his motions lifted by air, each turn a lofted inhale. Gowan’s musicality brought new detail to the score (by Edgar Meyer with Pharaoh Sanders). Montelongo, a friend of mine from college, moved differently amongst these other tall dancers, unafraid to take up space and glorious in all his breadth. He was commanding, deliberate.

Babatunji was powerful, but I found him most compelling when he slowed his movements for the next piece, the full-length Azoth that followed intermission. By this mark in the program, the dancers had stabilized themselves from the adrenaline that comes with that first performance back. They found themselves in the ground, showing off control and agency. DeVries assumed the opening movements as stunning architecture, steady and soft.

Costumes by Robert Rosenwasser (LINES Co-Founder, Executive Director, and Costume Designer) and lighting installation by Jim Campbell were elemental bliss, blue and gold hues that caught each other and embraced warmly. Guerra was astoundingly sure in her movement, finding stillness in moments impossible.

In Azoth, the gestural work is heavy. While some of the smaller, quicker gestures are lost in the speed – they don’t translate quite as well, coming off more sputter than specific – others are given purpose and land well within the work’s premise.

King is the master of contemporary ballet counterpoint. Though he doesn’t seem to care much for exact unison (it’s very clear that LINES is a group of soloists rather than a corps de ballet, and we like them that way), he manages to build on a vocabulary that is both universal and never tiring. It fits well with itself, but the levels, dynamics, and individuality of the dancers keep drawn out canons and breakouts interesting. The score, saxophone and piano by Charles Lloyd and Jason Moran, echoes this weaving contrapuntal expertise.

In this program, there’s no contact partnering until Azoth: the artists did not touch each other until the second act, and when they did it was devastating, tender, abundant with subtext. They grappled with self and community, lifting each other up, discovering their nature and finding or fighting it.

The last section of Azoth is a pas de deux by Cissoko and Montgomery, and it was wholly ubiquitous, omniscient. They listened to each other with ears intent, pushing and pulling with gentle strength until the audience became a part of the meditation. They spoke with every muscle, giving each one special care and attention. In that single spotlight, they were eloquent and at home in the comforting medium of human touch, and we were right there with them.

To visit the Alonzo King LINES Ballet website, click HERE.

Written by Celine Kiner for LA Dance Chronicle.

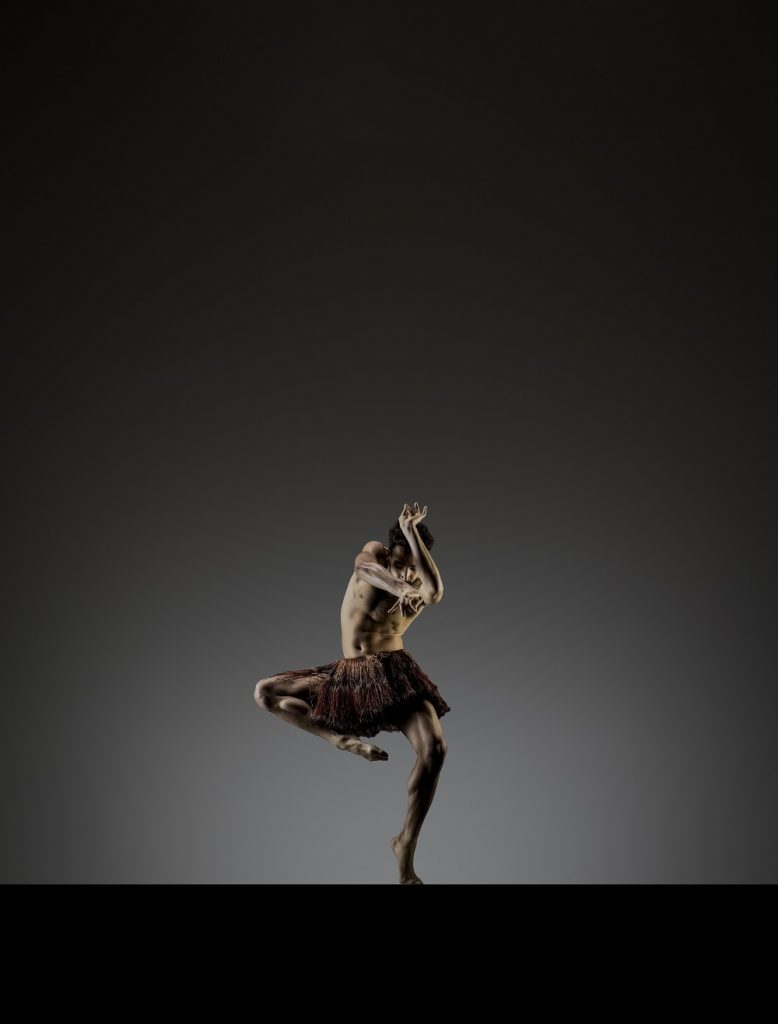

Featured image: AShuaib Elhassan – Alonzo King LINES Ballet – Photo: ©RJ-Muna