Kudos to Highways Performance Space for its commitment to diversity, the development of new works, and to the continued facilitation of artistic expression in a supportive atmosphere. All things great and good for the forward movement of any artistic endeavor.

Keith Johnson and his dancers presented “Drifter” – his take on the decade of the 60’s in four sections: ‘Drifter’, ‘Camelot’ (Mourning Glory), ‘My Vietnam’, and ‘Family’. The differences between the four sections were clearly marked and the segues were very smooth.

Johnsons’ notes state that this piece “investigates the ideology of the hippie generation and the increasing generation gap that signaled a divisive decade where feminism, civil rights, and social norms were challenged and explores the turmoil, confusion, distrust, and disappointment that occurred.” This is a very tall order for one piece of choreography to do; in four sections or not. Is there one ideology of the Hippie Generation? ‘Make love, not war” comes to mind but surely many other influences have made themselves felt throughout the movement, Hinduism and Buddhism as well as drug culture, communes, and free love.

The problem with taking on such large over-arching social and political issues is that they are very difficult to translate to the stage in terms of movement. If not developed with a specific narrative or time and place, such work often sits in a nether field of possibility without ever successfully transmitting its’ meaning to the audience. To do a piece about the 60’s is like doing a piece about the French Revolution or the Civil War – it is far better to pick a specific event and use the 60’s, the French Revolution or the Civil War as a backdrop to these events such as ‘Hair’ or ‘Les Misèrables’ or ‘Gone with the Wind’.

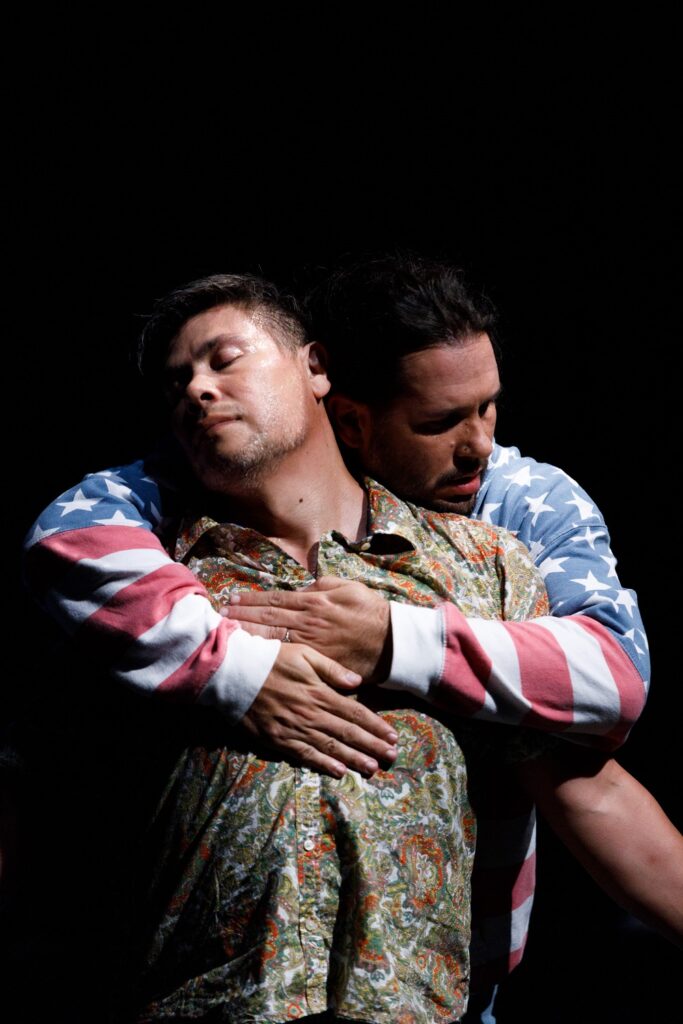

In the first section, “Drifter”, four dancers enter the space and begin moving. Haihua Chiang, Bahareh Ebrahimzadeh, Rogelio Lopez, and Andrew Merrell were able and up to the task of the movement. The only clue that this had anything to do with hippie culture was the costumes by Keith Johnson that they were wearing. These were appropriately floral and hippie-like in design, one being an American flag hoodie. The movement throughout was loosely based on contact improvisation with many weight transfers between dancers, lifts, and partnering. All movement was performed with neutral faces. I am somewhat fascinated by the exertion of movement requiring some use of technique without any emotion at all evident in the faces of the performers. Considering that this piece was supposed to convey ‘the ideology of the hippie generation,’ ‘the increasing generation gap,’ ‘turmoil,’ ‘confusion,’ and ‘distrust,’ I was at a loss as how to recognize those assertions in the movement happening between the passive dancers.

That being said, the dancers were fully committed to the movement and executed it well. The two solos by Paul Matteson (Camelot, Mourning Glory) and Andrew Merrell (My Vietnam) were great examples of this dedication. However, their movement was overshadowed and a bit overwhelmed by their soundscapes. ‘Camelot’ was overwhelmed by the poetry/song of Bob Dylan about the assassination of J.F.K., and ‘My Vietnam’ by the interview soundscape of a Vietnam veteran describing the horrors he encountered while serving in that conflict. Both soundscapes were fantastic in their depth and richness, but the movement onstage never reached that level of horror or interest, especially for those of us who lived through it.

This was also the case in the last section, ‘Family.’ Here we have various movements with the soundscape of music by John Luther Adams, Madonna and Karen Dalton, along with transcripts from interviews with Charles Manson, Patricia Krenwinkel and Leslie Van Houten. One of the dancers, Andrew W. Palomares, had the unenviable position of personifying Charles Manson as he pushed around one of the ‘girls,’ (Courtney Ozovek) and then turned to intimidate the audience. I suppose this was to underline his aggressive character. Other than blatant mime such as this it was difficult to see how the movement of the dancers illuminated the text of the Manson Clan. It seemed two different things were happening at once and the audience must choose between listening to the transcripts or watching the movement onstage. Both were separate and independent.

In his notes, Johnson wonders how the Manson Clan and others believed in the “hope” of the decade and how it deceived them. Pondering this dilemma is fine and can make for fruitful material onstage. One must, however, answer how the movement translates what the choreographer wishes to impart to the audience. Does the movement deliver these ideas to the audience? Perhaps there were others in the audience who may have thought so. The house was full and eager for what Johnson had promised in his Director’s note. Having lived through the 60’s myself and partly because of the nature of the loosely defined contact improvisation as the basis for Johnson’s movement, I was not able to connect the choreography to the large social and political issues of that tumultuous decade which he declared the evening to be about.

To learn more about Keith Johnson/Dancers, please visit their website.

To see Highways’ full line up of events, please visit their website.

Written by Brian Fretté for LA Dance Chronicle.

Featured image: Paul Matteson in “Drifter” – Photo by Colin Harabedian