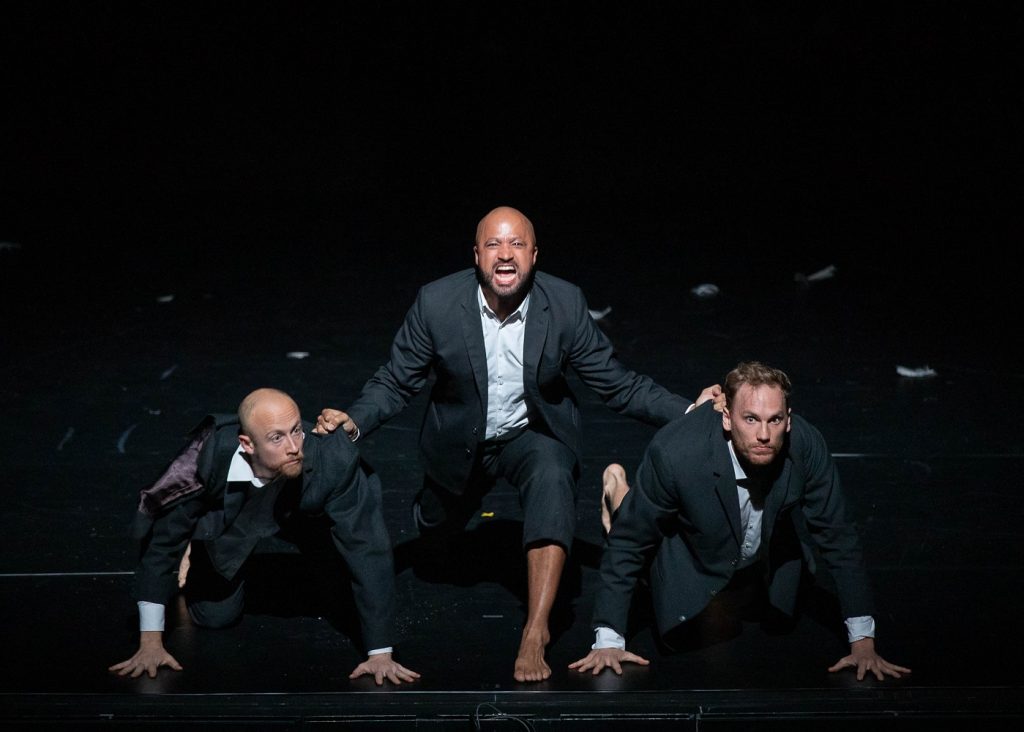

Presented by UCLA’s Center for the Art of Performance, Michael Keegan-Dolan and Teac Damsa’s Loch na hEala (Swan Lake) affords the audience no easy opening—before house lights go down, the curtain is up and an almost-naked Michael Murfi circles the stage, bleating like a goat and tethered with a rope to cinder blocks center stage. Several artists take their place in near silence as he circles and bleats, circles and bleats. He is finally accosted by Keir Patrick, Erik Nevin, and Zen Jefferson, who enter the stage in foreboding unison. They wash and dress him and he smokes a cigarette, demands a cup of tea and launches into monologue.

(Foreground form left to right) Michael Murfi, Alex Leonhartsberger, Erik Nevin, Zen Jefferson and Keir Patrick in “Loch na hEala (Swan Lake)” – Photo by Reed Hutchinson and CAP UCLA Royce Hall.

This is not just Swan Lake. It is an amalgamation of Swan Lake, the Irish folktale The Children of Lir, and the obituary of Toneymore resident John Carthy. In this convoluted triptych, Keegan-Dolan paints a Prince Siegfried that is instead John Carthy, a resident of Ireland with clinical depression and bipolar disorder who was shot outside his home in 2000. Alex Leonhartsberger’s Carthy/Siegfried (named Jimmy in this version) is young, suicidal. He wanders away from his elderly mother (Dr. Elizabeth Cameron Dalman) to find not just Odette (Rachel Poirer), but the swan and her three swan sisters (Anna Kaszuba, Latisha Sparks, Carys Staton), the children of Lir, at the lake.

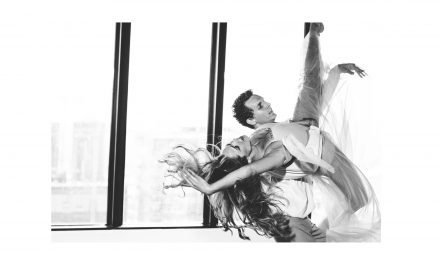

Rachel Poirier and Alex Leonhartsberger in “Loch na hEala (Swan Lake)” – Photo by Reed Hutchinson and CAP UCLA

Murfi narrates throughout, playing his own twisted political character and telling how he as a young man cursed the four sisters to animalia—they caught him mid-assault, silencing the oldest, and his curse silenced the rest. As he weaves the three tales together, Jimmy and Odette fall in love, comforting each other in their tortured fates until they meet death.

Keegan-Dolan’s choreography is not particularly complicated—the dancers reach big, Taylor-like shapes by means of Countertechnique transitions. They fraternize with gravity to meet the floor and are back up again in one sweeping motion, most often in unison but almost always in refreshing directional changes that appoint a sort of freedom to the space.

Patrick, Nevin, and Jefferson form one corps and genderbend their way into many roles, Keegan-Dolan allowing them room to play both criminals and suitors. Kaszuba, Sparks, and Staton form the other corps, shifting from playfully grounded young women to restrained swans with quiet protest. Poirer’s Odette exudes patience and revolt at the same time—she is captivating and gentle with Jimmy, but her anger is not to be contained. And Leonhartsberger is so thoughtful that just his footsteps gain your sympathy; he embraces the floor and remains supple, even when balancing on stacked cinderblocks over three feet high. The word ‘grounded’ understates him. He is silent, somehow floating as he lowers his center of gravity.

Michael Murfi, Erik Nevin, Dr. Elizabeth Cameron Dalman and Kier Patrick in “Loch na hEala (Swan Lake)” – Photo by Reed Hutchinson and CAP UCLA

At first meeting, Poirer and Leonhartsberger are inexplicably connected. The points at which they make contact spark with endearment, and they move as one in a seamlessly infinite phrase. They listen to each other (and I, in the audience, spill tears like I never have before). As their narrative becomes more layered, the connection intensifies but retains this quality. Their kinetic awareness is magic, breathing life into the love story despite dark and despairing circumstances.

Kier Patrick, Zen Jefferson and Erik Nevin in “Loch na hEala (Swan Lake)” – Photo by Reed Hutchinson and CAP UCLA

Musicians Aki, Awen Blandford, and Danny Diamond form a trio throughout, spending most of their time strewn across the upstage platform but coming down to join the theatrical cast for the party scene. Their score, mostly set but exhilarated by improvisational phrases, revoices old Irish harmonies in contemporary melodies and becomes a part of the story. Lighting by Adam Silverman, costumes by Hyemi Shin and sets by Sabine Dargent rebuild a world where all three tales can merge and where the intimacy of this small-town fable becomes the entire audience’s secret. Keegan’s writing, directing and choreography establishes him as not just artist, but auteur.

In what almost seems like a prologue, the entire cast is revived in a blizzard of feathers at show’s end. They spin and slide in abandoned play, inviting the audience into their joy and launching breathtakingly beautiful scenes into swirling bliss. And though it may seem difficult to come out of the dark after the famous deaths of Swan Lake, Teac Damsa had the whole theater laughing, crying, rejoicing—a hopeful note for a heavy subject.

Written by Celine Kiner for LA Dance Chronicle, November 12, 2019.

To visit the Teac Damsa website, click here.

For more information about UCLA’s Center for the Art of Performance (CAP UCLA), click here.

Featured image: