Prior to the pandemic, flamenco had been experiencing a small, but notable resurgence within the Los Angeles dance scene. Wider audiences were discovering the Andalusian tradition that had long been present in LA, opening the door for more masters to present their work to new and loyal admirers in theaters everywhere. From the Bootleg in Westlake to the Soraya in Northridge — each show was more publicized than the last.

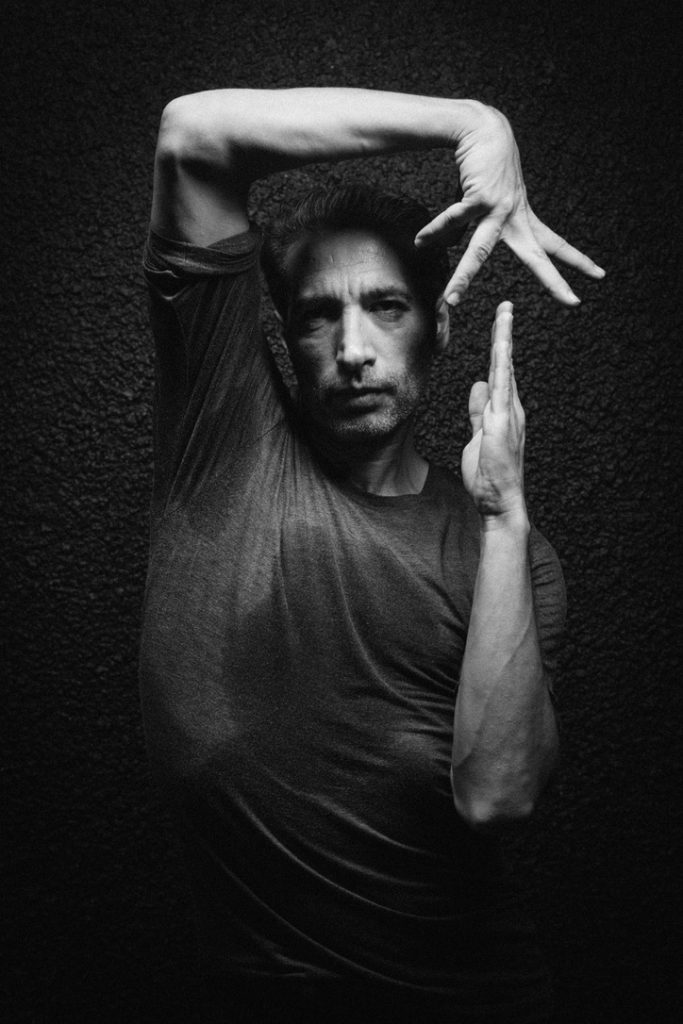

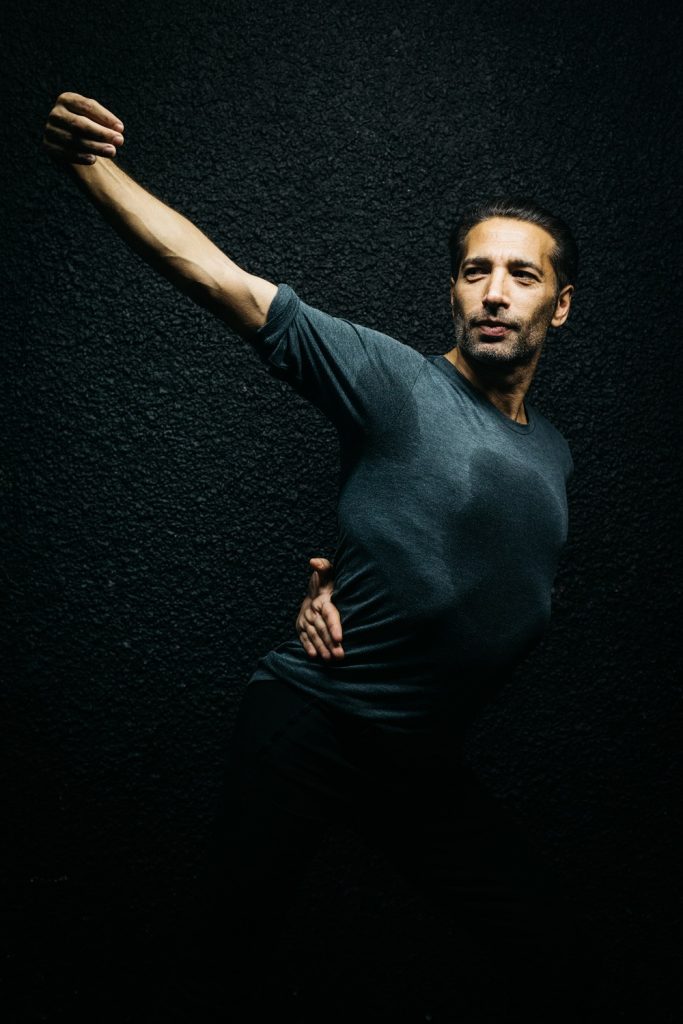

Israel Galván was ready to join their ranks with a live production commissioned by the Center for the Art of Performance (CAP) UCLA this year, but as quarantine’s long arm extended its reach into 2021, instead debuted a digital dance presented in association with UCSB’s Arts & Lectures, The Joyce Theater and Teatro della Pergola on March 6 on CAP’s website with alluring results. Maestro de Barra: Servir el Baile provided many homebound viewers with a refreshing and much-needed taste of travel by setting the piece in and around the artist’s local Bar Rodríguez in Plaza San Antonio de Padua, Sevilla. Inspired by the locale’s pre-Covid vibrancy, Galván’s contemporary choreography paid homage to the missing patrons while uplifting flamenco’s roots as an expression of the people’s spirit. Maestro de Barra: Servir el Baile can still be viewed free HERE.

The half-hour work was a serving of à la carte vignettes predominantly named after the tapas available on Bar Rodríguez’s menu. Each act explored a different side of life as it played out within this neighborhood hangout from opening to closing time. Though predominantly a solo, Galván did not dance entirely alone. He was sometimes joined by Ramón Martínez and María Rubio whose artful movements complemented his own. However, Galván remained the star.

The show began outside, in the rain, the natural elements adding to the rhythm of Galván’s zapateo (the elaborate percussion-like footwork) along the pavement, his boots suddenly appearing on a tray after a short pause to represent a literal translation of his title: serving up the dance. Once inside, some of Galván’s steps and gestures became direct reflections of the movements required to prepare the food and drink items. Others suggested the public’s general state of being while spending time at the bar.

“Ensalada Rusa” (“Russian Salad” — a classic potato salad eaten throughout Europe and Latin America) was the first titular scene to take place within the establishment and the one which diverted most from Galván’s musical theme. Rather than using Spanish canto (singing often paired with flamenco) or the atmospheric kitchen sounds to create his rhythm, classical music played overhead. The artist began performing his steps while holding onto the counter with one hand as if it were a barre. His strong, controlled moves became a flamenco-ballet hybrid resembling a controlled warm-up, slightly taming the Spanish dance’s wild side without dulling its flame. Arms opened and closed in second position, while the zapateo remained loyal to flamenco tradition.

The addition of musical elements to create new harmonies, which overlapped with the ambient noises in the gastropub added visual interest to the dance without overwhelming the movements (artistic advising by Pedro G. Romero, sound by Pedro León/Manu Prieto, filming/editing by Joaquin Aneri, and camerawork by Juanma Carmona). In “Ensalada Rusa,” Galván shifted his focus to a few slot machines in the corner of the bar and began playing them rapidly, their whirring creating a new, chaotic tempo, which overlapped with the classical music, before returning to the bar and continuing his artfully staccato balletic choreography. Similarly, in “Albondigas en Salsa Verde” (“Meatballs with Green Sauce”) the television set became the main instrument. Galván humorously reacted to a goal scored by Seville’s Real Betis Balompié team by lifting his arms up high, opening his hands, and molding his facial expression into one of both joy and relief, praising the moment with his eyes as well as his stance.

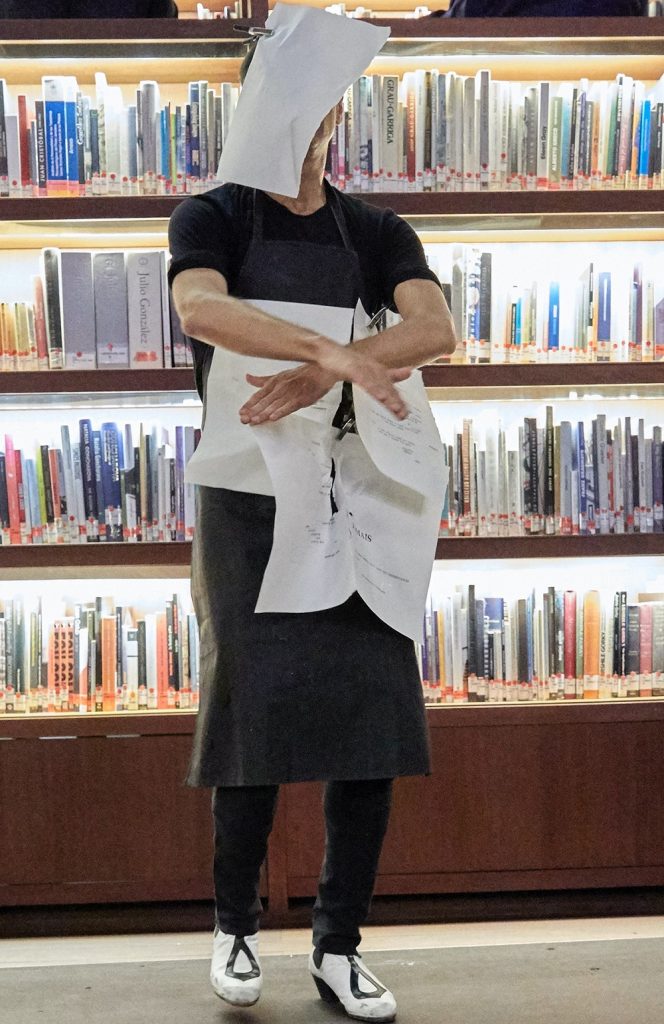

The piece’s more consistent musical trend came by way of Bar Rodríguez’s waiters (Pedro Díaz Romero, Julio Díaz Ruíz, José Pablo Gallego Gálvez, and Antonio Escalera Pastor) who not only ran the bar in the background in order to build up the sound Galván would move to, but also created their own canto in several scenes. In an early segment called “Adobo” (“Fried Fish”) Romero recited a large portion of (if not the entire) menu as percussionist José Carrasco played the countertop punctuated by jaleo (a chorus of verbal and clapping encouragement). Galván’s every gesture adjusted in accordance with Romero’s call, his zapateo adjusting to the length of each listed item. Much of his pantomime involved moving closer to the bar as though ready to order, then moving away and intermittently widening his arms, then bringing them in toward his mouth, his facial expressions imitating that of a satisfied customer.

In other sections, Galván redirected his attention to the food prep and kitchen work, exploring a new symphonic range by way of cutlery, ceramic dishes, and sizzling oil, often manipulating the melodies himself. “Flanenquín” (“Beef Roll”) assimilated the sounds of clanging plates and spoons, while “Almejas a la Marinera” (“Clams the Sailor’s Way” — soaked in salt water and prepared without tomato sauce) involved a more controlled knife against a block of wood. In these instances, Galván’s footsteps fluidly shifted between working with the soundtrack and against it. At times, his moves mirrored the cacophony. At others, the essence of the dance centered around the beat that emerged from the din.

Galván’s avant-garde routine shone brilliantly in chaotic acts, highlighted by high-energy moments wherein he would sit up onto the bar and swing his legs, or rapidly switch roles between client and kitchen crew between scenes. However, his incorporation of more traditional numbers with Alejandro Villaescusa providing canto, or softer kitchen sounds creating the music were no less exciting. “Chipirón a la Plancha” (“Grilled Squid”) was a straightforward dance performed to the continuous sizzling of a grill. The limited amount of space in the kitchen dictated a smaller stage upon which Galván delivered a speedy zapateo heightened with strong body pats when adding umph to his tapping. His synchronization to the speed at which the oil sputtered — fast as the squid was cooked, then slow as it was taken out of the pan — demonstrated an incredible amount of control.

Galván made sure to “Café y Copa” (“Coffee and Drink”), “Postre” (“Dessert”), and a “Taxi” ride home for the full experience of a day at the bar. As the film continued, many of the sections grew shorter and moved toward the outer portions of the establishment, featuring a few cars and pedestrians — according to post-credit interview given by Galván, a more muted scene than typically found on the street. Despite this, he did manage to produce a live audience thanks to a few locals above the bar whose attention was drawn to the zapateo in the bar’s doorway during “Café y Copa,” their interest mimicking that of the virtual viewer.

Flamenco is meant to be improvised both in terms of dancing and music. Much like a busy café, each evening, every “show” is unique. Galván’s decision to put them together makes him a maestro de baile en video as much as the Maestro de Barra. His film is a breath of fresh air in our quarantined lives. Even now, as regulations are lifting, and more things are opening up for Angelenos and Californians alike, it may take a while before we return to the fully casual feeling of going out without concerns. This glimpse into Seville’s similar state half a world away is a comforting reminder that many of us are look forward to enjoying the same things once the planet heals.

Israel Galván’s Maestro de Barra: Servir el Baile is still streaming free at CAP UCLA. To view, click HERE.

To visit the CAP UCLA website, click HERE.

[Editor’s note: Due to circumstances beyond our control, this review has been published some time after it premiered at CAP UCLA]

Written by Lara J. Altunian for LA Dance Chronicle.

Featured image: Israel Galván – Photo by Jean Louis Duzert 55