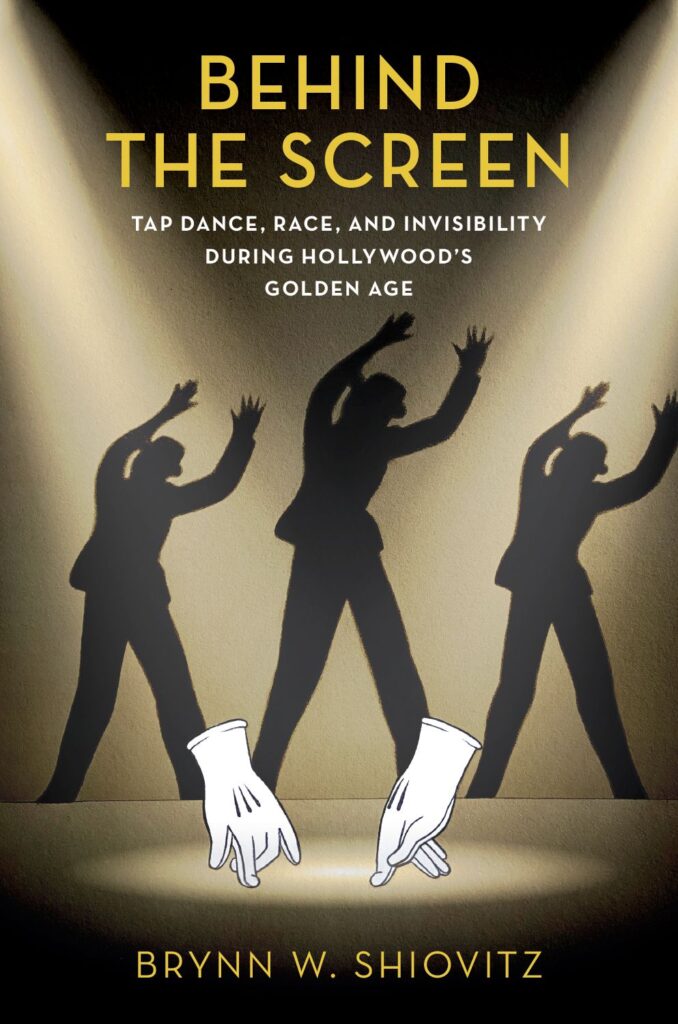

Do you love old movie musicals? Tap dance production numbers? Classic cartoons of the 1930s? And have you been shocked by blatant and casual racism in films of this era? Behind the Screen: Tap Dance, Race, and Invisibility During Hollywood’s Golden Age is a must-read book. Tap dancer, historian, and film scholar, Brynn W. Shiovitz takes a deep dive into what she calls covert minstrelsy and the guises Hollywood used to present blackface minstrelsy in ways that were simultaneously visible and invisible, audible and inaudible, overt and covert.

From the 1930s to 1960s, the Motion Picture Production Code’s prohibition of “willful offense to any nation, race or creed” (174) did not prevent Hollywood from recycling and capitalizing on racist tropes from minstrelsy. Blackface minstrelsy, America’s wildly popular mass entertainment, dated from the early 1800s. White men blacked up to perform imitations of African American dances, music, and songs steeped in racist humor. African Americans entering show biz were forced to black up also and conform to the genre. Minstrelsy, an incubator of early tap dance, also gave us Americana like “Swanee River” and a legacy of derogatory stereotypes. The dimwitted and lazy Sambo, the faithfully simple Uncle Tom, and the oversexed Jezebel infiltrated every level of popular culture for well over a hundred years and stood in mainstream White consciousness as “authentic” depictions of Black Americans.

One of the surprises of Behind the Screen is that the Production (also called Hays) Code did attempt to censor some racial caricature on film. Because controversy was bad for box office sales, Hays put the Code in place to minimize public offence and deter backlash from many sources. While the Catholic Church policed morality and women’s dancing bodies, the NAACP and Black press exerted pressure to ban racial slurs and pejorative representations of African Americans on screen. The film industry’s obsequious deference to the “Southern Market” meant miscegenation was banned, along with any hint of equality across the color line. (Censors okayed Shirley Temple and Bill Robinson’s duets because six-year-old Temple portrayed the slave owner of her genial, dancing, caretaker). And have you ever wondered why we see so few African American women tap and jazz dancers in old movies produced for White audiences? Southern leaders’ complaints effectively limited scenes featuring Black women dancers.

Behind the Screen details how the Code reinforced and perpetuated racial, ethnic, and sexual inequality in America. Shiovitz builds her argument through vivid descriptions of movie musical sequences that dance off the page and crackle with irony and outrage. Scholarship from film, music, performance, and cultural theorists adds to her analysis of the intersections of racism and sexism as capitalist tools that sold movie tickets, protected the industry’s bottom line, and affirmed White supremacy.

Anyone today who loves old movie musicals has had a moment of cringing shock. You know: you’re channel surfing and land on a beloved chestnut, featuring your favorite stars, fantastic songs, extraordinary dance sequences, and WHAM! The minstrel mask in all its grotesquery fills the screen. Faces coated with black grease paint, rolling white eyes, obsequious grins, and servile, white gloved hands that draw us, the viewers, into a master/slave scenario.

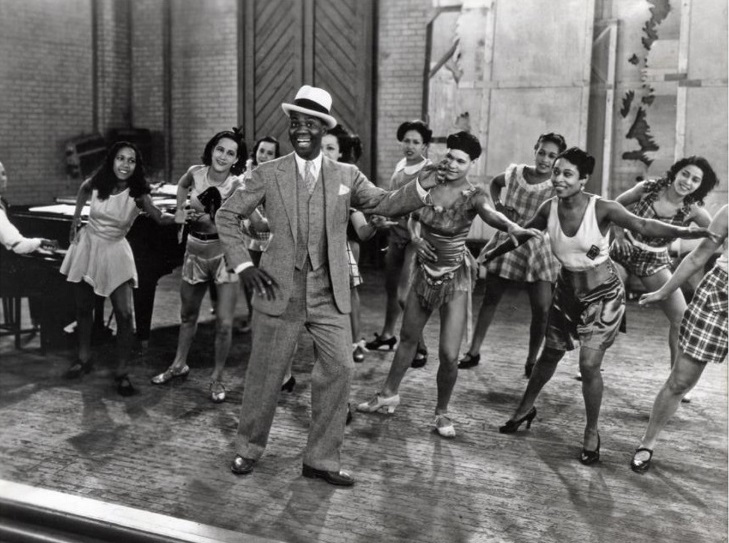

Bill Robinson and Fats Waller perform “I’m Living in a Great Big Way” in Hooray for Love, 1935. (courtesy of author)

Behind the Screen is the complex, multilayered answer to our contemporary moment of, “WTF?! Blackface? What was Hollywood thinking?!” Shiovitz peels back the makeup with her theories of the Sonic, Protean, Tribute, and Citational guises of covert minstrelsy.

The Sonic guise of covert minstrelsy can be heard when Bill “Bojangles” Robinson taps to familiar Stephen Foster tunes. Those nineteenth-century minstrel songs drag Robinson’s iconic jazz modernity back to the plantation. The Sonic guise is also at work when the Africanist aesthetic of rhythm tap can be performed by a White dancer, eliminating the necessity to hire a Black performer.

Eddie “Rochester” Anderson, Ethel Waters, and Kenneth Spencer in Cabin in the Sky (1943). Courtesy of author’s private collection.

Protean transformation scenes show White actors corking up for an old-time minstrel show-within-a-show (this signified patriotism during WWII). As audiences witness the White body smear on blackface, White superiority is reestablished over the Black Other. The Protean guise happens “by accident” when Mickey Mouse is blackened by an exploding cigar and bursts out singing, “Mammy!” or by inventive necessity when Shirley Temple hides from Union soldiers by boot blacking her face to “blend in” with her enslaved servants.

The Tribute guise is familiar to fans of Fred Astaire or Eleanor Powell. Both stars donned blackface to honor Bojangles. Shiovitz’s concept of the “Bill Robinson Effect,” describes how ubiquitous minstrelized imitations of Robinson in live action film and animation rendered his image even more famous than the man himself.

Ford Lee “Buck” Washington and John “Bubbles” Sublett perform a song and dance medley in Varsity Show, 1937. (courtesy of author).

Shiovitz coins evocative terms to describe how the Citational guise combines with other guises to embody caricatures of Black stereotypes. “Southern repossession” uses minstrel tropes to glorify nostalgia for a mythical, “simpler” time before Emancipation. In Cabin in the Sky (1943), the “Gabriel Variation” depicts African American religion as naïve and childlike.

Shiovitz argues–in mind-blowing detail–how 1930s to ‘40s cartoons contain vestigial examples of covert minstrelsy. Because cartoons slid by the Code standards forbidding “entertainment which tends to degrade human beings,” a dandified, Zip Coon frog could represent a tribute to Bill Robinson. Dehumanizing animations of Black artistry gave the studios a veneer of inclusivity, but the economics of these citations are chilling. Who collected the paycheck? Animators, not the living African American artists who inspired popular cartoons.

Behind the Screen delineates how covert minstrelsy removed actual Black bodies from the screen as White dancers–in blackface or not–performed Africanist music and dance styles and dominated Black sensibilities. This allowed only a handful of African American artists the opportunity to make a living in the film industry. Most of those were cast in roles that recreated tropes of Black inferiority.

Shiovitz stresses that blackface minstrelsy, no matter what its intent, effects racial violence. Her goal is to prevent “passive consumption of films, their imagery, and their sound tracks” (xvi). In the ongoing struggle against “Oscars So White,” Behind the Screen reminds us of the urgent importance of unbiased representation in film and media.

Behind the Screen: Tap Dance, Race, and Invisibility During Hollywood’s Golden Age can be purchased at Amazon, at Barnes & Noble Book Stores, and at Oxford Press.

For more information about Brynn Shiovitz, please visit her website and/or follow her on Instagram @bshiovitz and Twitter @movingsounds

Written by Margaret Morrison for LA Dance Chronicle.

Featured image: Bill Robinson performs atop a bar counter to Black patrons, backstage after performing his famous stair dance to a White audience in “Harlem is Heaven”, 1932. (courtesy of author).