On September 21, 2019 at 7:30 pm the Chapman University’s Musco Center for the Arts will open its 2019-2020 Season with Diavolo: Architecture in Motion. The Los Angeles based and internationally renowned company will present three works including VOYAGE (2018), TRAJECTOIRE (1999, 2000), and the premiere of the latest installment of its evolving Veterans Project, IBUKI.

This article was designed to be a preview of Diavolo’s performance at the Musco Center and it is. I was, however, very interested in how Heim became involved with the Veterans Project now in its third year. Members of Diavolo have been in residence at Chapman for several weeks and IBUKI will be part of the launching of the university’s Leap of Art Program. I travelled to Orange, CA. to watch part of a rehearsal conducted by Ana Brotons for IBUKI at Chapman University’s Partridge Dance Center and to interview Diavolo’s Artistic Director Jacques Heim, and two of the performers. The work is comprised of a total of 8 veterans and 11 civilians, and Heim selected one person from each category, Ayla Decaire (civilian/actor/dancer) and Ejay Menchavez, Jr. (veteran).

Born in Paris, France, Heim was what would be described now as Attention Deficit Disorder. He is also left-handed and dyslexic. He had a difficult time learning, was forced to write with his right hand, and believed that something was truly wrong with him and destined to become a bum living in the streets of Paris. He wrote poetry (terrible poetry according to Heim) and worked as a street performer. At his parent’s suggestion, Heim immigrated to the America because his grandparents lived here. “When I arrived in the US in 1983, I called my friends in Paris,” He said, “and told them that I think that I have discovered paradise. I think that they understand me.”

Heim had been struggling with what exactly he had been trying to accomplish with Diavolo since he founded it in 1992. Working with the Veterans Project has helped him discover the answer to that dilemma. He believes that we all are the same and each of us brings with us our own personal struggles. He believes that an artist knows instinctively that she or he must work on these problems through her or his art, whatever that art form is.

“I realized early on that I am a different kind of choreographer/artistic director.” Heim said. “I am not in the studio, standing in front of a mirror trying to come up with new movement. No! I love architecture for many reasons. I love the relationship of the human within the architectural environment. How it is affecting us emotionally, physically, and mentally.” Heim looked at me intensely and said, “Through the work of Diavolo, you cannot hide! You will discover your strengths, your weaknesses and what you’re about.”

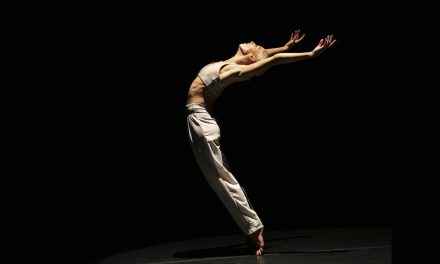

Jacques Heim in Rehearsal for IBUKI- Veterans Project – Credit: Musco Center photo by Alissa Roseborough

Fifty percent of Diavolo’s mission is creation and fifty percent is community outreach. The company wanted to find a community that paralleled its mission and realized that the men and women who truly sacrifice themselves are the veteran community. At first, Heim was resistant to working with or how he would be able to work with them. “To be honest,” Heim confessed. “I did not know who they are or what to do with them. I have no idea how to talk to them.” He was sure that they would “kick my ass” and think him strange. “I was not that courage a human being.” He said.

It was Dusty Alvarado, the Institute Director and the Director of the Veteran Project, who convinced Heim that he was more than capable to create work on veterans. He agreed and while driving to the first rehearsal had a discussion with himself about who he was as a director and how he worked with the members of Diavolo. He decided that he was the drill sergeant; an electrician, recruiting his dancers; and a football coach, and that he would use this same approach with the veterans; an approached that had led Diavolo: Architecture in Motion to be acclaimed around the world.

After welcoming this first group to Diavolo and beginning to work with them, Heim said. “To my big surprise they embraced what we were doing. They were engaged with what we were doing. They were thankful, humble, grateful, and in tears. I was kicking their asses physically, mentally and emotionally, but with love; not with the horror of war.”

“It was actually three years ago when I started working with the veteran community that I started to connect the dots,” Heim said. “Diavolo: Architecture in Motion is not your traditional modern dance company. I realized that what I am doing is not about creating only art. That is not my mission. My mission is to help young men and young women discover who they are.” While working with the veterans, Heim understood that this was the essence of what he had been working at for the past 27 years with Diavolo.

Heim’s work is designed to be intense and dangerous on purpose. It is not designed simply to impress. He believes that when you put people in the state of survival, they are drawn closer together and discover just what they are made of. “Eventually they believe that they can accomplish anything that they want because they have recruited themselves.” It is, Heim said, what Diavolo is all about.

Jacques Heim back to camera – DIAVOLO in Rehearsal for IBUKI- Veterans Project – Credit: Musco Center photo by Alissa Roseborough

When asked if the veterans ever experienced flashbacks or revisited memories of combat, Heim said yes. When this occurred, he stopped the rehearsal and everyone gathered together to discuss and comfort one another before resuming. He did not, however, treat them as fragile or damaged people. “No,” Heim stressed. “they were human beings with strength, with power, with beauty and with resiliency.” He said that they looked at him with the expression of let’s go! He stressed to them that the words no, impossible or I cannot do this were not in his vocabulary.

In an earlier interview Heim said, “”Our mission with veterans was to help them restore what they had’ to restore their physical and mental and emotional strength through the intensity of the movement of Diavolo.” The press release stated: “The project began with workshops lasting up to six months and soon some participants had confided to Heim that the experience had turned around a life that had become truly desperate. “I needed this,” one told him. “I needed this.”’

That first workshop was six months long, culminating in a presentation at the American Legion, Post 43 in Hollywood. The experience changed the lives of Heim, his company and the participants in the workshop. Heim knew that he was doing something very important. “The testimonials of some of the veterans was gut wrenching.” He said. “They explained how they had been on therapy for years and on drugs for years, but that this workshop experience was a different kind of therapy and that for the first time in years they felt like they could continue.”

From there, Diavolo connected with Lieutenant Colonel Dr. Art DeGroat, head of Veterans Affairs at Kansas State University. For years, Dr. DeGroat had been teaching that Art is the perfect medicine for veterans and he continues to be a huge instigator for the Veterans Project. He attends all the workshops and performances; here, Los Angeles, Tampa, in Kansas, North Carolina and everywhere else this project might take Diavolo and the project. The veterans in IBUKI will not tour with Diavolo. The company always work with veterans and civilians in each city that they travel to, but eventually there will be a larger work, titled S.O.S. (Save Our Souls) that will be part of Diavolo’s repertory and involving four veterans as part of the touring work.

Ayla Decaire is a Theatre Arts Major and Dance Minor at California State University, Long Beach. She has been following Diavolo for approximately ten years and was finally able to learn a Diavolo piece, Cubicle, and to attend a Diavolo performance this past summer at the CSU Summer Arts at Fresno. There, she met Dusty Alvarado who invited her to be part another event with Diavolo. Immediately following that, she was asked to be part of the Veterans Project at Chapman University.

When asked what this has been for her, Decaire said that it was “The most amazing experience, I think, of my entire life.” I asked why.” Knowing about the impact that the Veterans Project has on the veterans and having a lot of veteran family members myself,” She said. “I felt very strongly that I wanted to be part of it. Just being in the room with all these different people from different walks of life and who have all these different things going on in their lives; veterans from different branches of the military and the things that they saw and experienced. We all have this one thing in common. We are going to hold each other. We’re going to trust one another. I’m going to do my part and you’re going to do your part to protect each other and to support each other.” This is a feeling that Decaire does not experience out in her everyday life.

Decaire has become close friends with Vietnam veteran Kelly Edwards who lives in Long Beach and needed rides to and from rehearsals. She also lives in Long Beach and has gone beyond the call of duty by helping Edwards rehearse his part in IBUKI at his home and in the studio before the group’s warm up. Her family lives in Florida, so Edwards, his wife and their dog have become her family. “I feel like everything that we’re doing here with the Veterans Project is magical.”

Ejay Menchavez, Jr. is an Army veteran, serving six years with the 82 Airborne Division in North Carolina and doing several tours in Afghanistan. When he got out of the Army, Menchavez enrolled in Santa Monica College, transferring later to University of Southern California. It was in college that he took his first dance class and later studied at the Diavolo Studio where he was eventually invited into the Veterans Project.

Speaking about his experience with learning IBUKI, Menchavez mentioned that just like in the Army, the rehearsals are regimented. “We’re here every day. I wouldn’t say that it is like a nine to five job, but it is very consistent. Because we are here every day, things in my life have changed a lot. We work in a very specific way and it bleeds over into the rest of my life.”

I asked Menchavez if this brought up any memories of serving in the military. “I think what it brought up for me,” He said. “was the feeling of being needed.” Menchavez explained that he was what one would call a war fighter, and that he was very good at it. He was quickly promoted and at age 19 oversaw five other men. “After I got out I went from being a big part of a team; I was needed every day. Not only were the men part of my team and I told them what they were supposed to do, I also had to take care of their personal problems.” Menchavez realized very quickly that this wasn’t just a dance piece or a performance, but knew that the process was so dynamic that he had no choice but to be needed. “If I’m not there it’s very difficult for everyone, but also, people can’t do the things that I am capable of so they can’t do it without me.”

The set for IBUKI is a single six-foot square platform that is only eighteen inches high. It has 18 holes in it where 18 tall medal poles fit into. The poles represent the American flag, a weapon and they are a metaphor of being elevated by others around you. This simple black platform, which is so different from any of Diavolo’s other works, is called also called IBUKI. The word “Ibuki” has several meanings. For Heim, it means inner strength, and resilient enough to endure all and emerge beautiful.

DIAVOLO in Rehearsal for IBUKI- Veterans Project – Credit: Musco Center photo by Alissa Roseborough

“That is what I believe, and that is what I believe about my veterans and civilians.” Heim said. “The platform could represent a sacred space where your loved one’s ashes are buried, but as soon as you touch it, they feel alive, they feel strength and empowered.” Most civilians have absolutely no idea what veterans are about and it is for this reason Heim has joined together veterans and civilians. It is to hopefully create a bridge between the two groups.

Diavolo performs at the Musco Center for the Arts on September 21, 2019 at 7:30 pm. Tickets, beginning at $38, are available at www.muscocenter.org or through the Musco box office by calling 844-OC-MUSCO (844-626-8726). All print-at-home tickets include a no-cost parking pass.

Written by Jeff Slayton for LA Dance Chronicle, September 16, 2019.

To view the Diavolo: Architecture in Motion website, click here.

To view the full 2019/2020 Musco Center for the Arts season, click here.

Featured image: DIAVOLO in Rehearsal for IBUKI – Credit: Musco Center photo by Alissa Roseborough