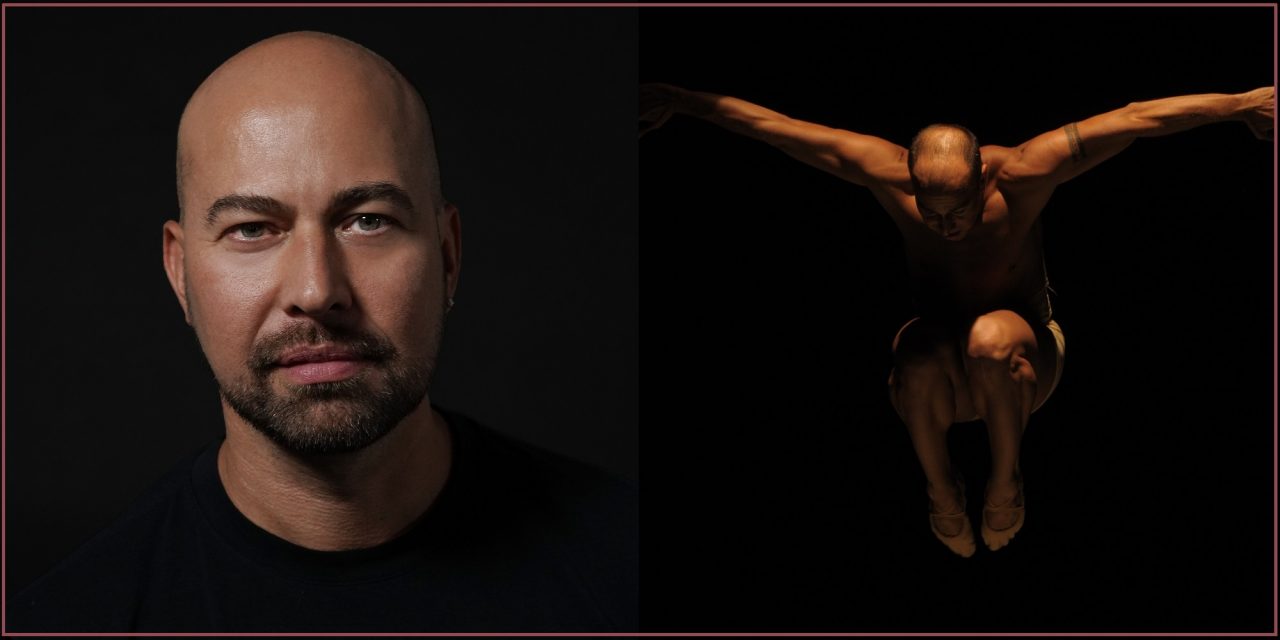

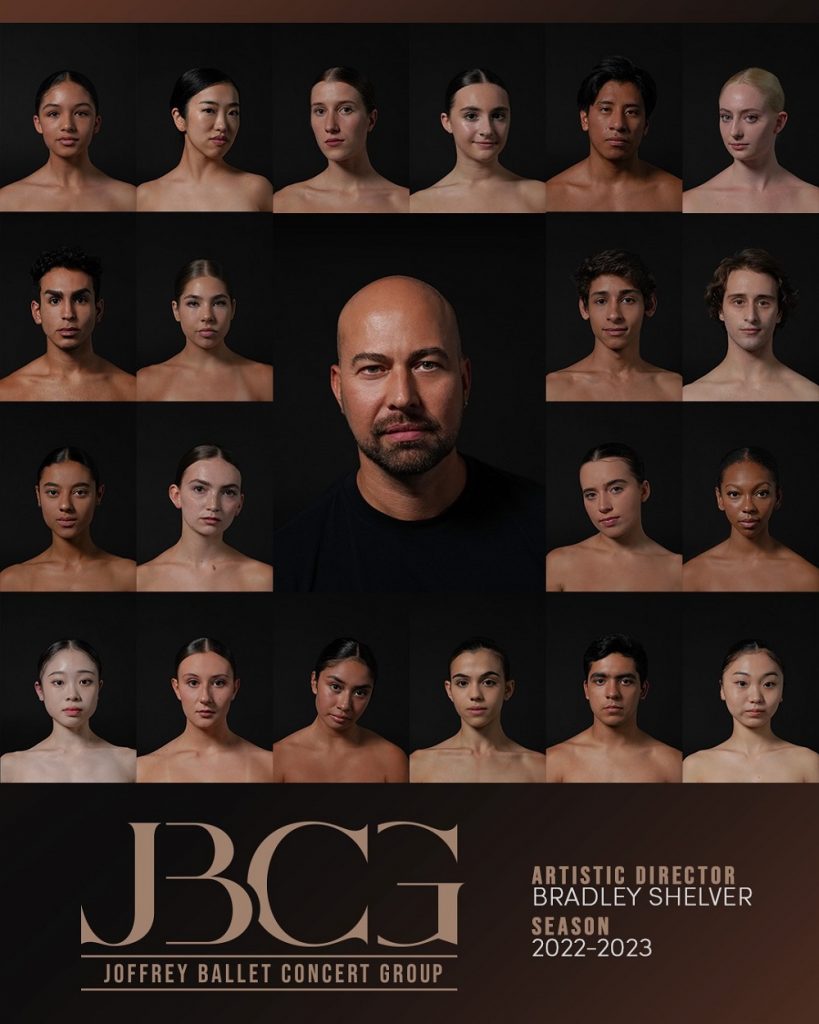

New York City’s Joffrey Ballet School has selected the eclectic brilliant Bradley Shelver to be the new Artistic Director of Joffrey Ballet Concert Group. Joffrey’s original group began in 1981, and with the departure of Davis Robertson and several years of hiatus because of Covid, Shelver’s appointment as the new AD opens a new inspirational, as well as aspirational future for the Group. The mission is to bridge the careers of young talented pre-professionals into the professional dance world. Mentorships, education and performances guide young dancers to not only perform the Joffrey/Arpino repertoire but move from historical to contemporary ballets, from Bournonville, Jooss, Balanchine, Battle and beyond.

Having the opportunity to speak to Shelver was a feast of hope not only for our young dancers but for those interested in the survival of dance as an art. I had so many questions to be answered in so little time, I started with his multifaceted training and professional career. This led to deeper understanding of what it takes to be a creative, curious and successful artist. So I welcomed him and inundated him with questions that tested his future hopes for the Group.

Joanne: Thank you so much for taking time out of your busy schedule. Just to get us started, in reading your credits I noticed you are radically eclectic. I’m curious about your incredibly expansive training and experience in many different dance disciplines, from traditional ballet to tap, jazz, modern, and contemporary dance. How did that happen?

Bradley: Well, I’m originally from South Africa and we have dances for everything. We have dances for weddings and births. And ah.. goats, fertility, the rain. And so it was more about expression, and it was about connecting, and community. So from a young age I wanted to dance and express myself. I didn’t really try to pigeonhole myself as… Oh, you’re going to be a classical ballet dancer, You’re going to be a contemporary dancer, You’re going to do tap and jazz. I just wanted to dance.

Joanne: Then please tell me how you decided to start. What was the thing that set you on fire? Your passion for dance? How did that happen?

Bradley: I definitely want to credit my father for that. Interestingly enough, because,

I started moving, I feel like… from the age of three. My parents used to clean the house and work in the yard on Sundays… that was the thing. Well, the radio always used to be on in the living room, and I used to just be dancing around, and my dad would look in the window, and he would see all of this. Then, on Sunday night we would have all the classical ballets that would play on TV from eight to ten on a particular channel. Now I was young, so you know my bedtime was six o’clock, seven o’clock, but on every Sunday my dad would let me sit up and I would watch Swan Lake and Don Q… I would watch all of the Ballets, and I would just be mesmerized. So at the age of four he sent me to audition. In the newspaper there was an advertisement for a school called the Performing Arts Workshop, which was actually started by an American man by the name of Jeff Corey.

Joanne: Oh, yes, I remember Jeff Corey from out here on the West Coast.

Bradley: yes, he came to South Africa, and he rented an old orphanage, and he converted it into this performing Arts Haven, Church, Mecca, I mean…It was just… we learned everything. We learned tap dance, costume design, singing, and ballet. Yes, just thinking about it now gives me chills. Where can we get that again?

So my father sent me there, and that was the beginning and end for me. You know I spent so much time there my father used to feel guilty, and he used to come and spend his lunch hours sitting in the cafeteria with me, and then he would go back to work. From there the fire kept going, and I couldn’t see myself doing anything else.

I did consider going into law school because my grandfather was a lawyer, and I thought of going into the law because I was always told I had the gift of the gab, which clearly I love. The intricacies of that language. You have to be very conscious of what you say and how you say it, because it’s all about context.

Joanne: So true… So moving onto your training, your ballet training in South Africa, was it in RAD (Royal Academy of Dance), was it Cecchetti? And where did that training begin?

Bradley: I attended the National School for the Arts. We learned Vaganova, Cecchetti, RAD and I learned ISTD (Imperial Society of Teachers of Dancing). ISTD is where I focused on my Jazz and Tap as well as ballet.

Obviously, classical ballet is the foundation of technique that we consider technical dance, but even before that, we were just moving. And then, the technical aspect of everything is just to hone that down, like a language. We study languages in schools so that we can best learn how to express ourselves. That’s sort of what I wanted to discover…how many different languages of dance could I assimilate and speak… so that I could best communicate.

What was wonderful about the legacy of dance, and particularly the classical ballet in South Africa was that you had all these phenomenal dancers from the Royal Ballet, from Kirov, and the Bolshoi, English National, and they got to a certain point where they were going to retire, and they had money in the UK (we were still part of the Commonwealth at that time), so they looked at South Africa; beautiful weather, you could buy a nice house, a car, and they thought, I’m gonna take my retirement there. So they did, and then when they would get there, they would get a little bored …and say to themselves, Let me start teaching.

One of my teachers, she just passed away recently, Vyvyan Lorrayne, was one of the original Four Temperaments. She was my ballet teacher and was Frederick Ashton’s muse. Just a phenomenal woman and an inspiration. We got the benefit of all of that, despite the horrific history that we had of segregation and Apartheid.

Well during that period we had this opportunity. The arts world was thriving in a very different way, and I think that was true for art everywhere. Even though it imitates life, for us in South Africa, it was almost an escape from all of that. Like the school that I went to, my parents refused to send me to any private schools because they believed that this is how it is in South Africa right now…but this is not the world. This is not how it should be, so we want you to have access to different cultures and people and experiences. We want you to be a well-rounded human being, and not just a person who thinks one way,

Joanne: Amazing! So your parents, were they South African, or European…or from another place?

Bradley: No, South African. My mother was Dutch and then on my father’s side of the family is Greek and British. That was their influence, and they lived in South Africa. But their parents were from that parentage. I think we had been sort of ingrained in South Africa for probably at least three or four generations.

You know what’s so wonderful about South Africa is [that] we are such a melting part of so many different people, cultures…food. we have the Indian lineage. You know traditional Indian foods, and we have German, British… many cultures, and so that in itself speaks to the very fabric of what we’re comprised of and so I think maybe that was also ingrained in me, and why I wanted to learn as many different languages as possible, and why I have had many different cultural experiences. I think that it definitely came from my parents and my upbringing for sure.

Joanne: Well, I started looking at your achievements, and I thought this is a man of the world, not just South Africa. Such a legacy it must have been for a young person. And because of the rhythms and the dance in South Africa, both from the black and white communities, how did this influence your life, your career, your viewpoint?

Bradley: You know because I got this scholarship, we were so far away from everything, even through Apartheid. We didn’t have exposure to any of these things. But when Apartheid ended, there was this flood of creativity and culture, and passion from everywhere, all the different companies and musicians. I had received an offer to join NDT 2 when the Netherlands Dance Theatre came to South Africa after Apartheid.

I remember Jiří Kylián was there. He actually taught company class this particular day, which apparently he doesn’t often do, but he was teaching company class, and these were the advanced students from my ballet school, The National School for the Arts. I went to the audition and afterwards they sat me down and said, We love the way you move, you’re very mature for your age. I was still in high school. We’d be interested in having you, join NDT 2 when the time is right.

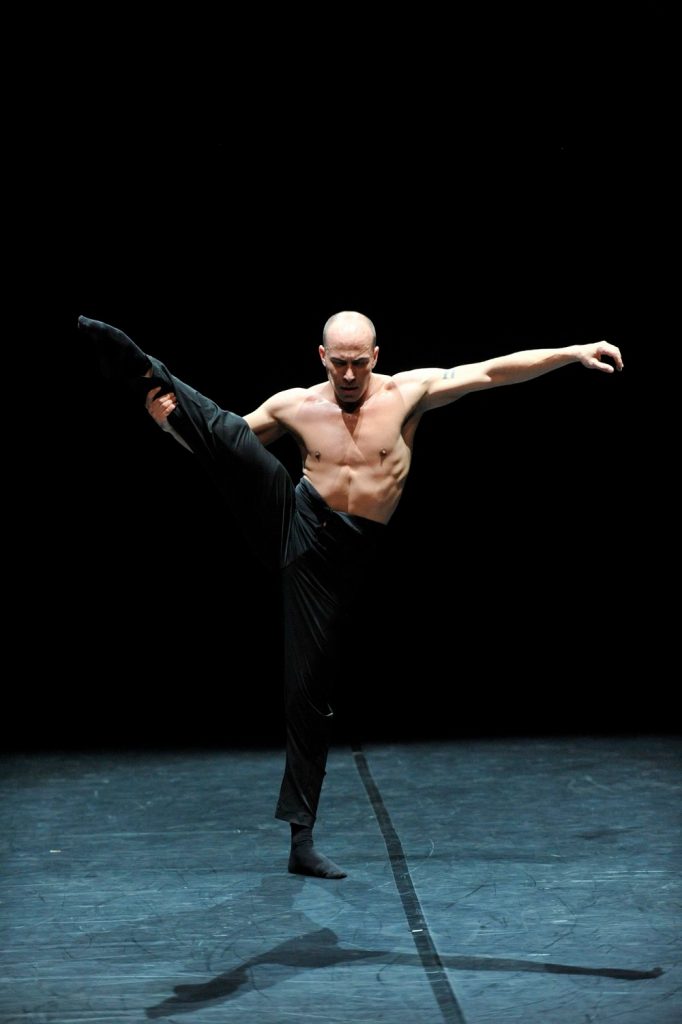

So, I had my heart set on NDT 2, until Alvin Ailey came to South Africa when it toured there for the very first time right after Apartheid ended. I just fell in love with that form of expression. That intense, magical way of communicating with these different styles, and they were ballet-trained, but they had jazz and African roots. And the music, and you know it was just… It was everything that I saw myself being.

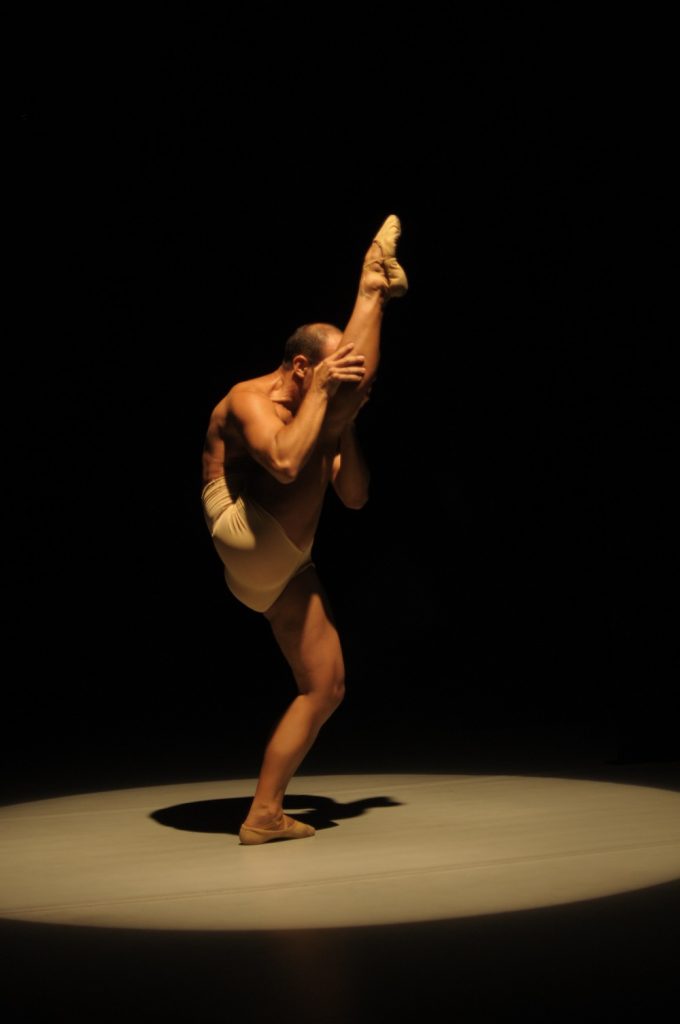

So I got a full scholarship from Ms. Judith Jamison to go to the Alvin Ailey School in New York. I went when I had just turned eighteen (January 1998). I didn’t know anyone. No family, no nothing, and was thrust into New York City and the Ailey school, and it was just the most magical experience ever. My father said, whatever it takes to keep you there, we will do. We don’t come from a super wealthy family and it was a lot of hard work and a lot of sacrifices. I missed home, but I just always kept my eye on the prize. I wanted to do this, and I wanted to do it well, and I didn’t see myself doing anything else. Also, I fell in love with the Horton technique, the complexity, the technical aspect, the difficulty. You really had to wrap your brain around the way the body moves in juxtaposition; one part of your body is saying one thing and the other part is saying another. That’s when I decided I want to be more of a contemporary dancer.

I’ve been lucky enough to stick with that and never had to work outside of my profession. Now I teach and choreograph, and I’m an artistic director, and have written a book. Just to be able to do all of that is lucky! I can honestly say that every single one of my dreams have come true.

That’s what I want for my students, that’s what I want for the dancers of the Concert Group, and that’s what I want for audiences, too. That’s part of the education that you have. This language of dance with that language of dance. Look how beautifully harmonious they come together! Is there any other way? Should there be? I mean, a lot of hard work, but I guess I’ve also been very lucky that people have also seen that drive and that passion in me and have been prepared to give me a chance.

Joanne: Well, it’s hard to deny! Even on paper. I was surprised at the depth of training and experience.

Bradley: thank you! That’s very kind. I always say, the Alvin Ailey organization gave me my life here. I could have left after my one-year scholarship… But we all have choices.

Joanne: Tell me more about your journey with the Horton technique and how you came to write your book on this icon of Modern Dance, something many dancers know little about.

Bradley: Well, there wasn’t a lot of information on Horton, there were only two books written about him prior to mine. There was his biography, and the textbook written by Ana Marie Forsythe and Marjorie Perce. I was studying from Ms. Forsythe and from Milton Myers, and what I loved about it, because I was so heavily ballet-trained, is that it just made sense in my body. But I was expected to take that language, and that understanding of the body to a different level.

Because I’d been doing a lot of solo tours and teaching in Italy, I was approached by a woman named Francesca Falcone in Italy. She was working with the University of Rome, and she asked me if I’d be interested in writing a book on the Horton Technique because I’d been teaching and giving lectures so much, and she wanted me to write the book from my perspective of the technique and its development.

So it originally started with me writing the book for the Italian dance community; but then there were financial issues in Europe, and in particular, Italy. She’d also approached someone to write a book on Graham, and somebody to write a book on Limón. So our series of books that were at the top of the list, fell all the way to the bottom. And I decided, well I’m not going to wait, I’ve got this book I’ve been researching and applying all these principles, and you know all this joy that I had inside me I needed to get it out. So that’s when the book appeared on the rest of the markets. So that was the journey.

Joanne: Looking over what you’ve done, it’s become clear that you have an underlying philosophy or belief that seems to be threaded through your entire life. Can you define it using a phrase that comes to mind every time you’re doing something? Or do you have a belief that just impels you forward, something that makes you so passionate about what you’re doing?

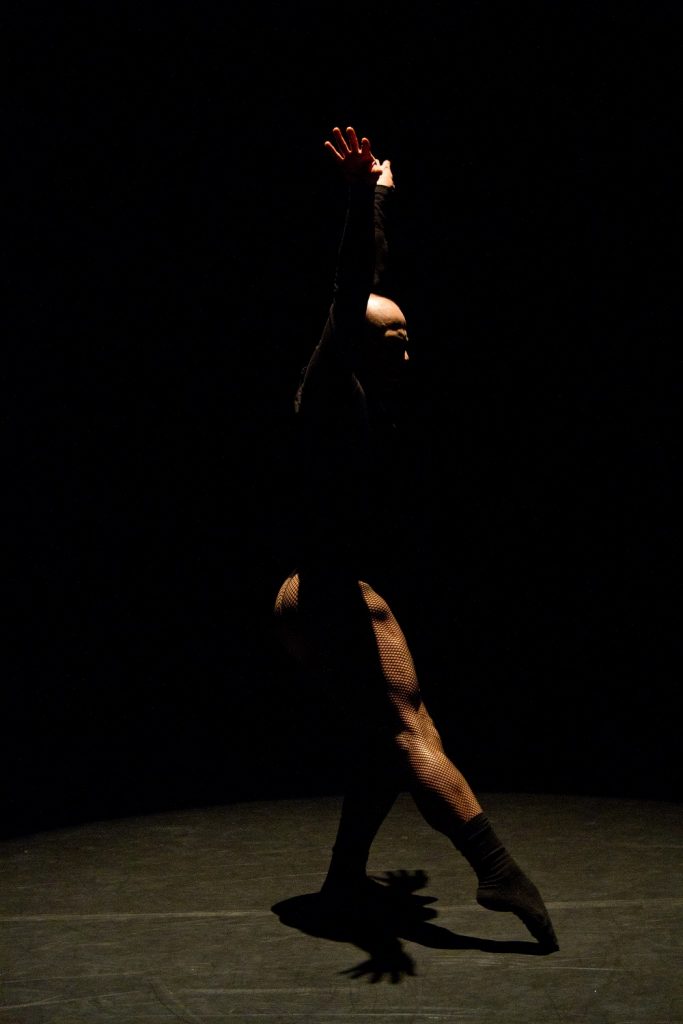

Bradley: It’s interesting when posed with that question, sometimes it’s just something inherent in you. I think it’s what I teach my students. We may not be saving lives like doctors, and even lawyers, or keeping someone in or out of jail, but we’re saving the human spirit. And I think what brings audiences, especially if you look at Covid, and what everybody turned to when they were sitting at home…The Arts, film, music, live streaming of dance, live streaming of all of it.

They didn’t turn to accounting or you know… Okay, a lot of home renovations. But it was that thing. Who am I? What is it that I have to say? And I think that’s the thing that impels me forward. But it’s not just about… Who am I? And what is it that I have to say? Because I feel like I figured that out when I was pretty young, but I think what impels me forward is; Who are you? And what is it that you have to say? In that context, especially the world that we live in today where voices were silenced for so long, people are now actually coming out and being able to express themselves. I think that’s what propels me forward.

Generationally, what I’m noticing is that in the last few generations everything is so flat on a screen, and everything is so …I’m not gonna call you, I’ll just text you. if you’re going to be an artist, that can’t be the only way, because you have to be able to communicate with people. You know, when you’re training it’s just for you. But after that it’s not for you any longer. It’s about your audience, your choreographer, about your artistic director… what are their needs? It’s because they’re also thinking about the choreography and the artistic direction, and their audience.

I think that’s the thing that really propels me forward. It’s not about me. It’s about, What can I do with this craft, this talent that I was born with, and these opportunities that I worked hard for… some of them I was given. What am I going to do with that now? And Who am I?

And that’s when I’m trying to get the generation of people, of my students, and also audiences to understand, like you are this person. You are good or you’re not, or you think this way or you don’t. Okay. But what are you going to do with that. Are you just going to sit with that and argue with somebody because they don’t feel the same way, or are you going to help guide them to see another perspective, or not? Maybe you won’t be able to change their mind. But maybe they’ll walk away from this experience of this or that conversation with a slightly more evolved sense of who they are. Oh, I really listened to this person, and I really got something from them, as opposed to just people yelling over each other, and the loudest one feels like they are the most empowered. I really think that’s what the artists can do. You know music and art, you know, visual arts and the performing arts. You can like it or not like it. Then, hopefully, it invokes the sense of…Well, why didn’t I like it, or why did I? What was it that I connected with?

Hopefully that you can transfer that onto somebody else. Okay, I didn’t like this person, or I did. Why? And how can I connect with them anyway? Because we all share the same human experience down the line. I think that’s what’s beautiful about the arts.

Joanne: And I’m sure that your early experience with apartheid probably has something to do with that.

Bradley: Yes, beautiful, that’s true. Thank you.

Joanne DiVito: So you explained to me how you push the envelope. Joffrey was just that kind of person. So I guess my question here might be, because you are now the Joffrey Ballet Concert Group’s new leader, could you tell me a little bit more about how you see it advancing and expanding?

To continue reading Part II, please click HERE.

#####

To find out more about the Joffrey Ballet Concert Group, please visit their website.

Written by Joanne DiVito for LA Dance Chronicle.

Featured image: Bradley Shelver, Photos By Michael Waldrop And Fernando Ferreira, Merged By LADC