Vladimir Varnava’s ISADORA, A Tribute to Isadora Duncan in Two Acts featuring prima ballerina Natalia Osipova made its debut at the Segerstrom Center for the Arts this past Friday, August 10, 2018. Set to the Cinderella music by Sergei Prokofiev, this was anything but what one might expect of a classical story ballet. From the choreography to the amazingly beautiful and surreal video graphic designs by Ilya Starilov, ISADORA was an interesting deviation from the norm. This is not a ballet about the dancing style of the iconic Isadora Duncan, but an extremely condensed and obscure account of her career and often tragic life. As the title states, it is a tribute to an incredible, pioneering dance artist.

There have been several films made about Isadora Duncan as well as many books written about her life, but I feel a bit of her history is necessary for those readers who may not be aware of Duncan’s stature within dance history. Born circa May 26, 1877 (this is the date on her baptismal certificate; some sources say May 27, 1878), in San Francisco, California, Isadora Duncan became what many believe to be one of the “Mothers of Modern Dance,” a title she shares with Martha Graham. She was a trailblazer who created and taught a never seen before free form style of movement, and was one of, if not the first, to perform barefoot onstage. Sadly, there is very little film footage of Duncan performing.

Isadora Duncan lived in Chicago and New York before moving to Europe, where she studied Greek mythology and visual iconography, which became the inspiration for her art. She then moved to Europe and before her great success in 1902 in Budapest, Hungary, Duncan performed in homes of the elite society. She met Paris Singer, a man of luxury, who was the son of inventor and industrialist Isaac Singer. Tragically, their two children and nanny drown in 1913 when the car they were in fell into the Seine River.

Following this tragedy, Duncan moved to Russia and in 1922 married poet Sergey Aleksandrovis Yesenin. Her ties to Vladimir Lenin and the anti-Bolshevik feelings in the US, caused her to be ostracized and she swore never to return to America. Her marriage to Yesenin failed, Duncan returned to Europe, and died on September 14, 1927 in Nice, France in a bizarre accident. One of her long scarfs which was part of her persona, got caught in the back wheels of an automobile in which she was a passenger. She was 50 years of age. That same year her critically acclaimed autobiography, My Life, was published.

Choreographer Vladimir Varnava trained at the Khanty-Mansiysk branch of the Moscow State University of Culture and the Arts. In 2008 he joined the Music Theatre of the Republic of Karelia, going on to perform lead roles in classical and contemporary ballets. Since 2011 he has worked as a choreographer and has lived and worked in St. Petersburg since 2012 working with principle dancers such as Igor Kolb, prima ballerina Svetlana Zakharova and now Natalia Osipova. He is the recipient of the Golden Mask (2010) and Harlequin (2011) theatre prizes.

Born in Moscow, Osipova began her formal ballet training at the age of eight at the Mikhail Lavrovsky Ballet School. At the young age of 18 she joined the Bolshoi Ballet as a member of the corps de ballet. In 2010, she became a principal dancer at the Bolshoi Ballet, but resigned from the company in 2011, citing “artistic freedom” as her reason for leaving, and joined American Ballet Theatre as a guest dancer for their Metropolitan Opera House season. On 8 April 2013, it was announced that Osipova would join The Royal Ballet as a principal dancer. Osipova is considered one of the best ballet dancers of this generation.

Because she loved Prokofiev’s music, Osipova first asked Varnava to create a new version of Cinderella especially for her. When asked which she loved more, the music or the story, Osipova confessed that it was the music. Varnava suggested the story of Isadora Duncan because, like Cinderella, her life was filled with overcoming obstacles and tragedy.

The result was visually breathtaking from the moment one walks into the theater. Starilov’s video graphic designs created a world of emotional strife and darkness that followed Duncan throughout her life. The stylistic and often Greek inspired sets and costumes by Galya Solodovnikova, coupled with Starilov’s designs, caused fantasy to clash or intermingle with reality, and to bring deep thought and humor into the production. The ballet was also enhanced by the live music performed by The Mikhailovsky Orchestra, Conducted by Pavel Sorokin.

Varnava’s portrayal of Isadora Duncan was that of a woman who was driven by one of the nine Greek muses, Terpsichore (Goddess of Dance and Chorus). Performed beautifully by Emily Anderson, it was Terpsichore who inspired Duncan to disregard the restraints of ballet technique, to take off her shoes and to move to Europe and beyond. Sadly, Terpsichore could not prevent the human side of Duncan to continue to be crushed by repetitive tragedies involving water and automobiles.

Starilov used projections of a stormy ocean, a theater becoming flooded with dark water and flames licking at barren trees to highlight these recurring events in Duncan’s life. A dance version of the Greek style chorus dressed in all black appeared throughout the ballet to help tell Duncan’s story, including white Greek tragedy masks.

The choreography was often stark, minimal and stylized to hint at the free form style of Duncan, but it never attempted to copy her dancing. Osipova, who is a very versatile performer, executed this with amazing grace and ease; including the very difficult floor work often associated with modern or contemporary dance. Perhaps this was aided by her work in Twyla Tharp’s In the Upper Room, for which she was awarded Russia’s most prestigious theatre prize, the Gold Mask.

What weakened the work for this reviewer was the many abrupt transitions from one period of Duncan’s life to the next. I did appreciate how the baby blue suitcase always appeared when it was time for her to move, but other events were glossed over or heavily depended on the video graphics projected on the backdrop. I found it very ironic that Varnava chose to portray Paris Singer (performed expertly by Joshua Equia) with movement straight out of Monty Python’s silly walks. Granted, the ballet would have been too lengthy had all the details been presented, but I am not sure anyone who did not already know the story of Isadora Duncan was able to follow the story. The very abstract version of how Duncan died, for example: unless one knew that she died by her scarf becoming entangled in the spokes of a sports car’s rear tire, would they have recognized that as portrayed on the backdrop?

That said, Varnava’s ISADORA is a visual treat and the performances by Osipova and Anderson are well worth going to see this ballet. It is a ballet that breathed new life into the art form of story ballets.

The entire cast, which is not that large, gave a wonderful performance; many of whom danced several roles. The Ballerina was performed by the lovely Veronika Part; Alexey Lyubimov did a great job with his portrayals of Vladimir Lenin and the Dance Teacher; and Vladimir Dorokhin was masterful as the poet Sergei Yesenin.. The dancers who performed Isadora’s family and some of whom also danced the roles of the Nymphs and Isadora’s followers were Margot Hartley, Sydney Keir, Evita Zacharioglou, Josep Maria Monreal, and Tanner Ryan. The Satyrs were Cemiyon Barber and Dante Adela.

For more information and tickets, click here.

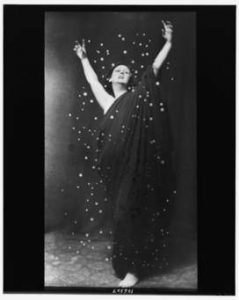

Featured image: