Even with the plethora of entertainment options available in the modern world, there is nothing better than curling up and disappearing into the world of a good book. If it transports you to a time and place completely removed from the present, is imbued with ballet, intrigue, passion, and redemption, and one can faintly hear Tchaikovksy’s Sleeping Beauty floating in the background, one might reach a state of nirvana. Lucy Ashe has written just such a novel. She was generous enough to sit down and discuss the book and her intersectional identities as a dancer, author, teacher, and student of history.

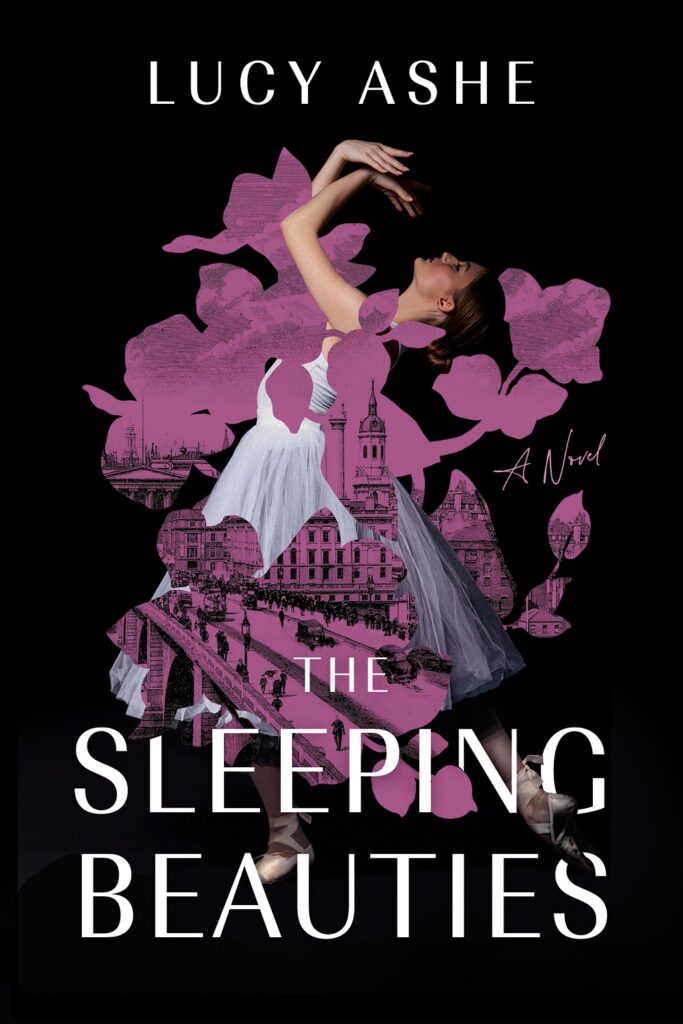

The Sleeping Beauties, Ms. Ashe’s newest book, releases in paperback on September 10. Set in and around wartime London, the book centers on the intertwined stories of Sadler’s Wells (The Royal Ballet) ballerina Briar Woods and Rosamund Caradon, a country widow with a ballet-obsessed adopted daughter, Jasmine. The book is wonderfully hard to categorize. It is both historical fiction and a mystery novel. Ballet, dark fairy tales, and music are intricately woven throughout, giving it the texture of a heavily embroidered tapestry. It woos the reader with love of all kinds; maternal, platonic, romantic, and with the all-consuming passion for ballet itself. It is also a beautiful reminder of the role of the arts in challenging times.

This is not a book review, but I do encourage you to read The Sleeping Beauties and Ms. Ashe’s previous novel, The Dance of the Dolls. (released as Clara and Olivia in England) For balletomanes, the inside look at the early years of the Royal Ballet is intoxicating, and enough historical figures are sprinkled throughout to make you feel like an eyewitness to events. Margot Fonteyn is not yet the beloved prima ballerina assoluta of all time, but a teenager under the watchful eye of her mother. You can smell the dusk and smoke as it wafts off of the costumes as the Covent Garden Royal Opera House is returned to the ballet from its wartime use as a dance hall for the citizens of London.

Ms. Ashe has an extensive dance background, as a student and professional. She trained at the Royal Ballet until age 16, then shifted gears, attending an academic school but continuing to dance as a scholar at the British Ballet Organization. She earned a diploma in teaching ballet from there and taught ballet while attending Oxford University where she earned a degree in English Literature. During and after university she danced professionally, even traveling to Tokyo to perform as the classical ballerina in a multimedia performance piece. However, like many, as she transitioned into a full-time English teacher position, her ability to remain competitive as a dancer waned, and she let it go.

I became a full-time English teacher, I just couldn’t keep up with the dance classes, and very quickly, I was no longer able to do the things that I used to be able to do. I sort of let it go at that point, but I couldn’t get it out of my system completely. I think that [ballet is] your identity when you’ve been dancing so intensely, you know, six days a week from a very young age, and a boarding school as well. That was my identity. But I felt that the ballet world had cast me out of it, and I wasn’t quite sure whether I knew the way to find my way back in. So I gave myself a bit of space from it.

It took Ms. Ashe about eight years to return to dance; when she did, it was through writing.

I decided that one of my favorite aspects of my time in the Royal Ballet School was learning about dance history; our academic lessons about the history of dance and the Ballet Russes and the early years of the Royal Ballet. So I immersed myself in ballet research and historical research. I wrote Dance of the Dolls, got an agent, and a book deal, and I suddenly felt that I could have this new relationship with ballet.

Ms. Ashe approached her new relationship in a really beautiful way. The emphasis is on the history and the rarified light that can surround classical ballet.

One of the things that I was really struck by in my research was how important ballet was for the British population during the Second World War. It was during those years that the British people developed a love of ballet for themselves, rather than thinking that ballet was just Russian dancers; The Ballet Russes coming in and putting on a show. They created it and in doing so created a national identity for dance. It was very important that these dancers traveled all around the country on these terrible train journeys, you know, reusing their pointe shoes way too many times in cold, cold theaters with hard floors and just two pianos rather than a proper orchestra. There were not many men either, because most of the men had been called up. They worked really hard. They put on so many performances during the wartime. They were bringing entertainment to people. There’s something very beautiful about that. And it reminds me of the wonderful way that ballet can bring joy to so many people.

The language of The Sleeping Beauties is also unique. It sounds very much of the period, not as if written by a twenty-first-century author but rather as if it is being told in real-time. It allows for the raunchy, sexy, day-to-day realities to be a part of the story. In concert with that very real language is the incorporation of the original, extremely dark fairy tale origin story and the masterful use of metaphor and poetry. The prose elevates the story and plot and leaves easy and trite characterization behind. The characters in the novel are flawed and often hard to like. It makes the book quite compelling. I asked Ms. Ashe about this, as many writing programs emphasize a leading character who is “likable.”

Why are we drawn to needing to separate people into good and evil? I think because we long for certainty all the time, we’re always looking to know the answer to be sure. One thing I realized as I was writing this book; we can never really be certain about anything. It [life] is about trying to learn and live with uncertainty. That is the challenge, not only for all of my characters but also for myself. It is about not knowing the answers all the time, not knowing if someone likes you or doesn’t like you, or if you’re saying the right thing or the wrong thing. It’s much more messy than that.

The fairy tale was a direct path into the story; the Sadler’s Wells Ballet returned to Covent Garden in 1946 with The Sleeping Beauty. The fairy tale also serves as a backdrop to create complicated characters. It is a wonderful way to incorporate fantasy and history into a fictional story. The score of Sleeping Beauty also figures into this mélange of good and evil, circling back to the main theme of the book.

The score is fascinating because of the different motifs that it has. Carabosse, the Lilac Fairy, and Aurora dance between one another throughout. There are moments in the score when they get a bit confused. For instance, when the Lilac Fairy is sending the castle to sleep, you hear the motif of Carabosse, the evil fairy, coming in. You start to think, is this the right thing to be doing? Is sleeping through difficulty and change and trying to retreat from it all, is that another form of a kind of denial?

Many dancers move into writing by writing a memoir, but Ms. Ashe took a different path.

I don’t think I would ever want to write a memoir of my time as a dancer. One reason is that my understanding of myself and the different parts of myself and of that time are constantly shifting and changing. I’m coming to terms with them in different ways. I don’t really want to set them down on the page when I might, in one year, have a different feeling about it. I’ve got therapy for that! But I do write about it in my fiction. It is there. It is all there. I find that fictionalizing it gives me this wonderful distance, sort of a playful distance that I think allows me to be more emotionally honest, and like I’ve got more courage to delve into it.

Her first two books were not based in the ballet world at all and were not published, but she refers to them as her “barre work,” saying they prepared her for the two that followed. There was a long period of writing poetry and short stories. With The Dance of The Dolls, she gained an agent and publisher, but that full journey took eight years. She has already written her next book, another piece of historical fiction, but one leaves the world of ballet behind for a different kind of intrigue.

It’s called The Model Patient, and it is set in the 1960s. It’s about an ex-fashion model who becomes obsessed with her psychotherapist. She finds out that her childhood best friend is engaged to marry him, and everything starts to unravel. It’s a psychological thriller, which has been really fun to write, and again, required a lot of research, which I love.

I want to return to Ms. Ashe’s current relationship with dance and the beauty of the art form. She has returned to classes in New York. The adult ballet movement, in a way, is quite revolutionary and quite revelatory. It’s very healing for so many people.

One thing that I’ve been really struck by since moving to New York City is how much ballet there is for adult beginners. And I think this is so brilliant. And I’ve been taking ballet classes at the Mark Morris Dance Center, which is two minutes from where I live. Sometimes I go to the more advanced classes, but my favorite one is the Saturday morning beginning ballet. It is probably too easy for me, but I just love it. I love being around all these people who are enjoying trying ballet; doing ballet for well-being, for exercise, and just because they love the movements. I hope that my books can be part of that movement to see ballet not just as bullying and elite and painful with toes bleeding. Yes, it could be those things, but it can also be for everyone.

Lucy Ashe is a fascinating person and her books are worth curling up with. I suggest doing so with a cup of spiked cocoa and some shortbread biscuits! And definitely play Sleeping Beauty in the background!

You can buy her books at your favorite bookstore or online.

Written by Nancy Dobbs Owen for LA Dance Chronicle.

Featured image: Lucy Ashe – Photo by Alex Fine.