Entering the artistic realm of the world-renown Greek artist, Dimitris Papaionnou, was like perusing through a book of Greek mythology, experiencing moments of historic global events, witnessing an archeological dig, or slowly walking through an museum of classical art; all with great wonderment and a whisper of wry humor. Surprisingly, Papaionnou’s The Great Tamer (2017) had only the one performance at CAP UCLA’s Royce Hall on January 11, 2019. Not surprisingly, the performance was totally sold out.

We entered the theater to find a lone figure lying on a gray, curvy landscape made up of large vinyl and plywood panels. The surface resembled photos of our moon’s landscape or the desert on a faraway planet, yet it felt far more familiar; as if it was a secret place one often retreated to for quiet reflection. Soon, the man stood, stepped into a pair of black shoes, tied their laces and began quietly scanning the entire audience. His face showed no emotion, as if he did not expect us but was not disturbed by who or what he saw.

After untying the laces and stepping out of the shoes, the man walked upstage to a small back table and began undressing. This was the first of many such actions to reveal both men and women totally nude. Papaionnou appears fascinated with the human body; how it moves, how it is constructed and what outside influences have on its development. He is well versed in his country’s mythology, world history, art and the human psyche.

As the house lights dimmed to dark, the completely altered Royce Hall stage was transformed into a slideshow of wondrous images.

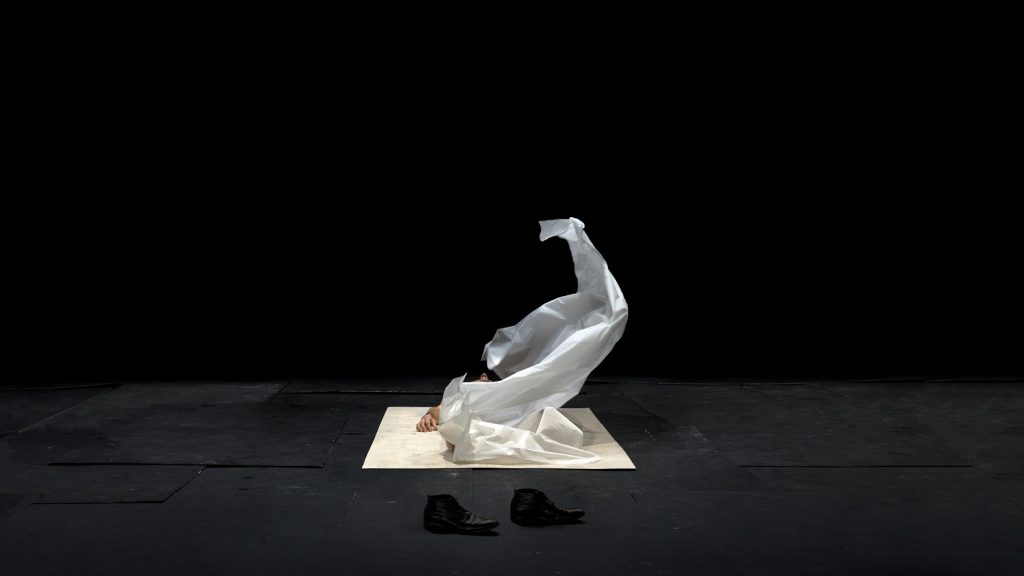

To the slow playing music of Johann Strauss II’s An der Schönen blauen Donau, Op. 314 (The Blue Danube), this same nude man walks to center stage, turns over a panel to reveal its white side and lies down on his back. He is joined by another man who covers him with a silky white sheet, as if covering the dead. A third man enters, lifts another panel and lets it fall, causing air to blow the sheet off and expose the nude man’s body. This process was repeated several times (each time more rapidly) and it reoccurred later during the evening but with a different conclusion.

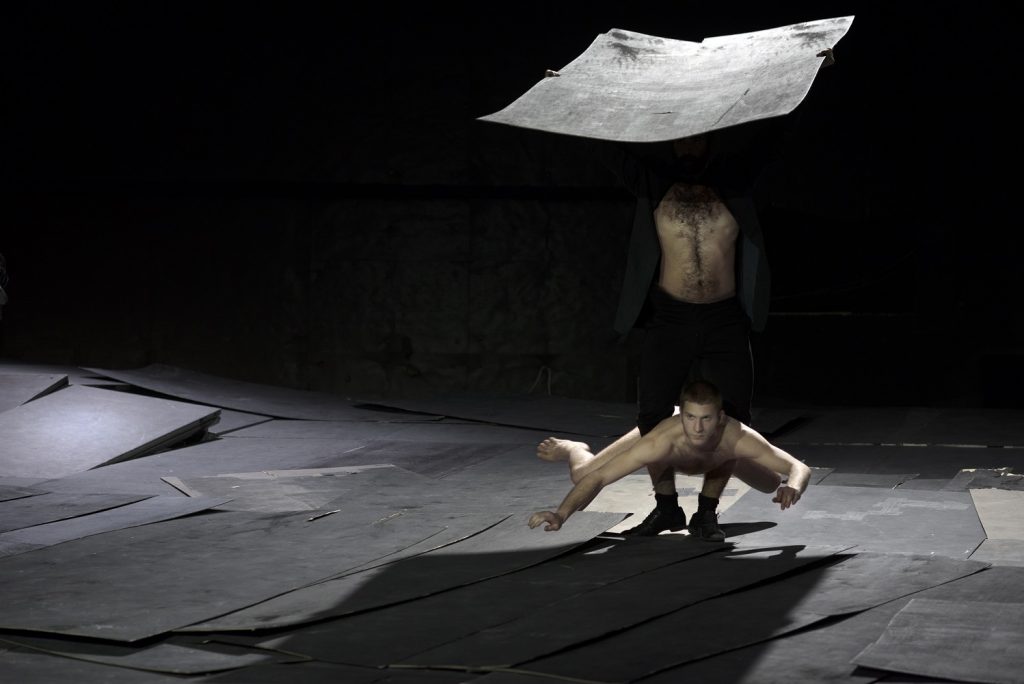

The dancers/actors worked with the panels throughout the production, lifting them to expose a hole, water for bathing, a grave or to unearth body parts which were then beautifully and ingeniously reassembled into a human being via Papaionnou’s inventive staging, gift for creating vivid metaphors, and exquisite timing.

Papaionnou has created over twenty-five productions ranging from large spectacles with a cast of thousands, to small, more intimate works. They have been seen in a variety of venues, ranging from his famed underground theater in Athens, to ancient theaters, Olympic stadiums, and well-known theaters around the world. It was his stunning creation for the Opening Ceremonies at the 2004 Olympic Games in Athens that brought him wider recognition.

In The Great Tamer, we watch as a nude man is operated on while awake. Including the costumes, the scene was a direct reference to Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson of Dr. Tulp (1632). The surgeons removed the man’s organs and sawed off his limbs. Again, through Papaioannou’s extraordinary staging, the operating table transformed into a dining table covered with a white table cloth, plates, silverware and candles, where the now plainly dressed surgeons cannibalized their victim’s body parts. It would have been totally grotesque had the scene not been so amazingly choreographed and masterfully performed.

We watched as a fully suited astronaut slowly and arduously walked downstage, his/her heavy breathing amplified. The astronaut searched the surface for a specific place and when found, began breaking up the ground to unearth soil and rocks. A beautiful movement section took place as the rocks were lyrically handed off to other dancers dressed in black as if the stones were floating through space. The astronaut then reached down into the hole with both hands and slowly pulled out the nude body of a blond-haired man. Another astronaut joined in and both partially undressed revealing that the first was a woman and the second a stocky, bearded man. The unearthed man was loving cradled by the woman, giving him life and the knowledge to stand and walk.

There was a male duet where one man moved his empty shoes with his hands, which controlled the motions of the other’s legs, giving a whimsical meaning to walking in someone else’s shoes. Another pair of black shoes were stepped into by a male dancer who discovered that they are rooted to the earth. With great resistance, he unearthed them, exposing their roots and managed to exit the stage by walking on his hands. The image recalled the work by the Belgian surrealist painter René Magritte.

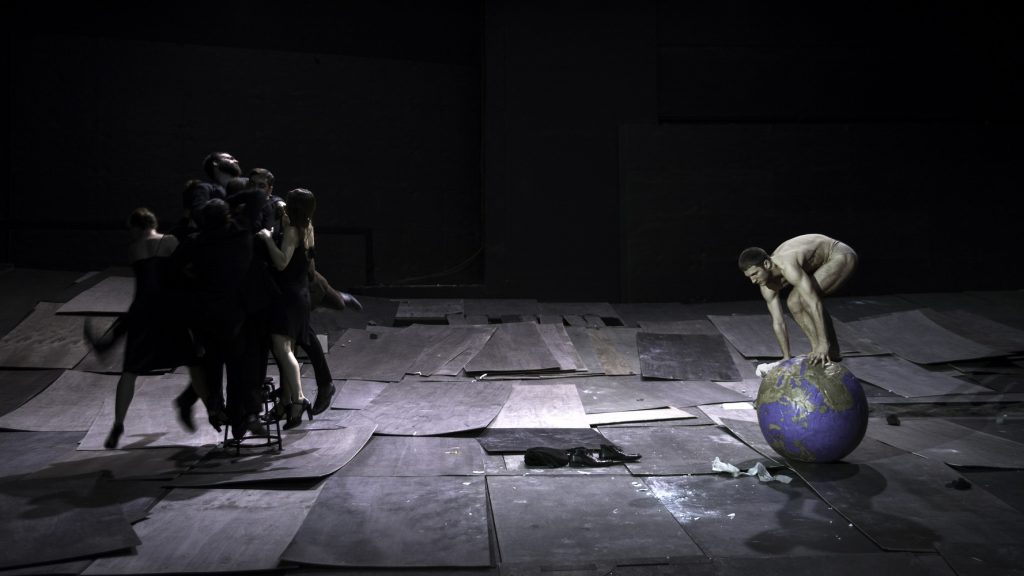

Throughout The Great Tamer, Papaionnou referenced works by painters Botticelli, Goya, and El Greco, plus the Greek gods and goddesses Demeter, Narcissus, Venus, and Atlas. A nude Atlas enters carrying the world on his shoulder. The globe was passed around to be performed with ala Charlie Chaplin in his iconic 1940 film The Great Dictator and a man balancing atop it like a trained seal as it rolled around the stage; a metaphor for how we humans abuse the earth and one another?

Three dancers, two men and a woman, used uncovered body limbs to form the body of a strangely shaped woman. Her torso sat atop two hairy nude legs, one from each man. It felt strange in the way one might feel visiting a circus freak show, but humorous in how it was portrayed. Disassembled body parts were another of Papaionnou’s reoccurring themes. A man dug up arms, legs, a torso and a head, then using the trapdoor riddled stage and humorous choreography, he reassembled them into a living, breathing and yes, nude man who simply walked away.

Another disturbing scene was after a man discovered a nude woman’s body, he seemingly sliced her open just below the rib cage with his bare hand and sluggishly, no painfully moved her along the stage and down into a hole that mysteriously opened. This was the one image/metaphor that I found difficult to watch. Man abusing woman.

One of many breathtaking scenes involved a nude man climbing inside a cave created by many of the panels being artfully moved from beneath the floor. As he lay there, a multitude of wheat shafted arrows rained down about the stage, creating a field of wheat. A woman (the Greek goddess Demeter?) enters to soak her tired feet in a water filled hole while the other cast members harvest the crop and fill her large clay pot. Once filled she quietly stands, lifts the pot and carries it offstage. The evening was filled with one rich and amazing image after another. Some subtle, some referencing iconic paintings or events like Buzz Aldrin’s 1969 walk on the moon. The Great Tamer is saturated with scenes of life, death, reincarnation, enlightenment, and human fragility.

Sound was used to accentuate and set one on edge. A man who, during a previous scene, had fallen offstage returned encased in a body cast. Another man proceeded to break off the plaster with the sound of it loudly amplified. After the chunks of plaster were collected and placed into a plastic trash bag. He violently threw it to the ground causing the lighting to abruptly shift to darkness and an ear-piercing screech of intentional audio feedback assaulted our ears.

The panels along the back of the stage were moved in a slow-motion wave like a card trick by a lone actor walking over one upturned panel at a time. Those same panels were re-positioned to form a white wall that became the shadowy backdrop for a small battle scene. Actors occasionally stood in groups watching from the back like Greek gods and goddesses atop Mt. Olympus peering down at mankind. Clothing was constantly removed and put back on. Body parts appeared not to belong to their owners. Death came and death was cheated, and a skeleton was unearthed, and its skull set upon the book of knowledge.

The final scene was somewhat capricious. In a special spot light at the foot of the stage, the skull rested next to orange peels left there during an earlier scene. A man removes a small gold and silver square of foil, and using bursts of his breath, kept the foil afloat above his head. To keep it afloat, he danced, ran, turned and dipped while he puffed beneath the foil. As the lights faded, the foil performed its own solo as it swirled, flipped and flittered into darkness. Perhaps this was a metaphor for humanity’s fragile relationship with all of earth’s elements and life’s struggles over the span of one’s life time.

At the end of the evening I felt like I had witnessed a slow motion collision of the experimental theater director Robert Wilson, choreographer Pia Bausch, artist Robert Rauschenberg and all the world’s knowledge stored inside the mind of Dimitris Papaionnou.

The amazing cast of The Great Tamer included: Pavlina Andriopoulou, Costas Chrysafidis, Dimitris Kitsos, Ioannis Michos, Evangelia Randou, Kalliopi Simou, Drossos Skotis, Christos Strinopoulos, Yorgos Tsiantoulas, and Alex Vangelis.

The Great Tamer was conceived, visualized and directed by Dimitris Papaionnou. The looming and ever shifting set was designed in collaboration with Tina Tzoka; Artistic collaboration for costumes with Aggelos Mendis; the lighting that continuously created new and unique landscapes was in collaboration with Evina Vassilakopoulou; Sound Design by Kostas Michopoulos; Sculpture Design by Nectarios Dionysatos; Costume-Prop Painting Maria Ilia; Assistant Director Stephanos Droussiotis; and Assistant Director and Rehearsal Director Pavlina Andriopoulou.

To visit the official site of Dimitris Papaionnou, click here.

To view the promo video of The Great Tamer, click here.

For more information on performances at CAP UCLA’s Royce Hall, click here.

Featured image: The Great Tamer by Dimitris Papaioannou – Photo by Julian Mommert.