Barak Marshall is a few minutes late to meet me in the lobby. Not because he was stuck in traffic coming eastward from Brentwood, where he takes care of his elderly parents. No, he just got wrapped up in some work in his office upstairs. I’ve just sent him an email—a “just making sure you know we were supposed to meet five minutes ago” email—when the elevator door opens. Barak steps out of it and spots me sitting in the corner, mouthing I’m sorry the second we make eye contact. I forgive him instantly. I’m one of many students that require his attention. He is one of few faculty members that actually makes the time, and he’s not even full-time faculty.

Several dancers have gathered in the hallway. Their repertory class starts in a few minutes; the class where we first met Barak. A few of them have just performed excerpts of his work, Monger, at the Laguna Dance Festival. It’s a festival founded and directed by our school’s vice dean—comprised mostly of classical ballerinas performing for old white people, to persuade them to donate fractions of the money they bleed in order to support slightly less classical dance work. Barak’s choreography is far from classical ballet (he’s simultaneously had all the training in the world and none of the training at all, but we’ll get into that later), but Monger is quite a crowd pleaser.

“How was it?” he asks a group of juniors on his way over to me.

“They loved it,” one girl volunteers, and the rest echo.

A couple more dancers file into the lobby to prepare for their evening classes, and Barak has the same conversation with each one of them. They all give the same response—they loved it, Jodie loved it, we love performing—but Barak welcomes each answer as though he’s never heard it before. His black hair is particularly mad-scientist curly today, and the curls bounce as he nods in earnest at the students. He’s proud of them, and he already knows that, but he’s making sure they know, too.

Marshall finally sits down to answer my questions, but not until he’s heard updates from all the dancers. I don’t actually have that many questions for him, and I know his answers to these ones. It’s more of a formality, making sure that I quote him directly for an upcoming article. But if I’m trying to answer the real questions, no thirty-minute interview will compare to learning Monger last fall; having enough context to perform the piece required that we spend many hours with Barak, learning about his lineage.

He was dancing

He was born into a legacy to begin with: Barak’s mother, Margalit Oved, graced Israel’s Inbal Dance Company as a principal dancer for over a decade. Known for her storytelling, singing, and beautifully generous gestures, Oved was praised by modern dance’s mother, Martha Graham herself. When Oved retired from the company in 1965, she moved to Los Angeles to teach dance in UCLA’s department of World Arts and Cultures.

Barak always tells us that he grew up there, underneath her drum as she counted the dancers in and out of movements. His blood was steeped in rhythm if his genes didn’t have it already, and the dance studio was his second home. Like any teenager, as he grew up, he rebelled against the thing he knew best, swearing he would not become a dancer.

Barak finished high school on the west side and packed his bags for Harvard, where he studied social theory and philosophy and aimed straight for law school. He didn’t get quite that far, though. After finishing his undergraduate studies, he moved across the country for—gasp—a woman. It didn’t work out.

Barak accompanied his mother to Israel in 1994, when she was appointed artistic director of the Inbal Dance Theatre. Six months later, his aunt fell ill. She had helped raise him in Los Angeles while his mother was working—their bond was strong to say the least. But she died, six months after the move to Israel, and Barak’s mother had no time to grieve with a company to manage.

This is the part of his career that Barak refers to as umbilical whiplash, the part in which he runs desperately hard and fast in the opposite direction of his mother’s legacy, and the harder and faster he runs, the harder and faster he is pulled right back into dance’s iron grip. He was not trained—he knew his mother’s Yemenite traditions and gestures, he knew how to sing (boy, did he know how to sing), but he had never trained formally in dance. Yet he sat in on rehearsals, helping his mother here and there, supporting her the best he could. One day, a company dancer caught him mourning his aunt in the studio and was astonished initially. It turned out, however, that nobody was genuinely surprised.

He was dancing.

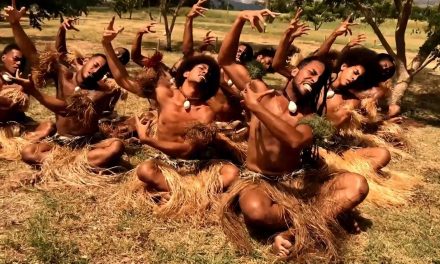

The company dancer watched for a few days and finally confronted him, insisting that he make a work for the company to honor his aunt and heal the wounds of loss. He finally agreed, and she filmed his process in the studio, translating it into dancer-language: one-two-threes and five, six, seven, eights. It was built out of the things he knew from his mother, and the combination of his Yemenite and Israeli heritage with his anti-training set him apart from the contemporary ballet aesthetic that monopolized the dance world.

The work, titled Aunt Leah, was a booming success—Marshall’s career took off in the direction he thought least possible. He toured Europe with the company, and in 1999, dance pioneer Ohad Naharin asked him to become Batsheva Dance Company’s first in-house choreographer. Naharin, a contemporary dance giant, is known for his insanity, to put it lightly. His temperament is notorious, and though he may make rash decisions, he does not make wrong decisions. Marshall accepted his offer, choreographing for Batsheva until a severe leg injury halted his course in 2001.

Rehearsal revelations

It’s important to note here that Barak still does not have any formal training. He didn’t pick up ballet or jazz or modern along the way, a la Wayne McGregor (an artist who went straight to choreography and skipped the dancing). His choreography is of the movements he knows bold gestures and Yemenite exclamations, each imbued with a very specific meaning. For Barak, context is everything. If he’s not telling you a family story with each movement, he’s doing an Israeli accent or showing you how to properly spit at the person beside you. His choreography is laden with rebellion: servants against mistress, women against men. These themes are especially strong in Monger, which illustrates ten servants in the basement of a cruel rich woman, doing everything they can to resist breakdown from begging mercy to spitting in her food. Of course, we as dance students don’t have the same background in social structures, so Barak ends most rehearsals with a tale of life in Israel. Usually, he starts his stories when he can tell that we are tired, overwhelmed with midterms and exhausted by other dance obligations. It’s merciful, but also economic and efficient. We come to rehearsal the next day with eyes slightly brighter.

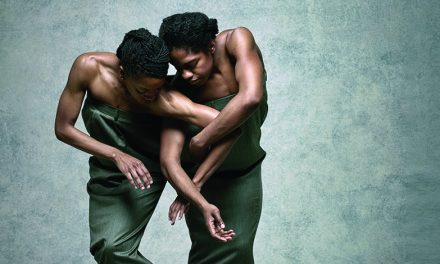

Celine Kiner and classmates in rehearsal with Barak Marshall for “Monger” at USC Kaufman (Photo by Carolyn DiLoreto/Courtesy of USC Kaufman)

Barak’s always making sure we’re not hurt. In the entire piece, four small counts of the choreography are especially hard on the knees: he doesn’t make us do those four counts until the week before the show—just a few times, to make sure we can actually do it. Maybe it’s because he wasn’t raised as a dance student, but he doesn’t have that twisted voice in his head that prevails in our conservatory. You know, the one that tells you that dancing on an injury is just proving your strength and dedication.

Monger is almost entirely an ensemble piece, and almost all of the choreography is done in unison. The movement is contemporary, performed barefoot, with fast and furious gestures (four gestures per one count). Nobody has a solo—Barak just wants to make sure that we’re all ourselves, within the greater narrative.

“I don’t want to see the choreography,” he says. “I want to see you. Show the audience how valuable you are because you are.”

Dancers are given a literal voice in Monger, and in his other works, “Rooster,” “Wonderland,” and “And at midnight, the green bride floated through the village square.” Besides just the exclamations throughout the choreography (hey!, no!, shh!) there is a microphone center stage.. Besides just the exclamations throughout the choreography (hey!, no!, shh!) there is a microphone center stage. The dancers speak monologues that Barak writes himself, some based on seminal philosophy works and some based on Israeli folktales and some just cheeky banter. He coaches the delivery, asking for accents wherever possible and most often giving the note, “louder. Less hesitant.” In Monger, the texts begin as a pleading last effort not to be let go: Mrs. Margaret, please! It’s not my time yet. I’ll give you anything you want, whiskey, cigarette? Mrs. Margaret! And end as a biting f-you (there are gestures for that, too): I spit in your coffee. I spit in your food! She wears your dresses! So, do I! Students are empowered through this role as servant. We’re yelling insults onstage—we never do that. We do pas de bourrée, jeté, pose, smile. The women are pushing the men, spitting at them. We are encouraged to make real spitting noises. One girl actually spits by accident, and Barak yells, “good!”

We are not students anymore. We are people, and Barak knows us. He tells me one of the reasons he accepted the invitation to return as an artist in residence this year: he wants to know the students better. He wants to see how he can make the work better for us.

The gestures take a long time to learn and even longer to master. They’re incredibly specific and you have to convey so much meaning with just your hands. My hands are really small, so I grow my nails out because every bit counts. I end up dancing almost too fervently and accidentally scratch my shoulder in one gesture. I break skin, but it’s fine. I could care less about the blood: the work is important. Once you learn the gestures, the satisfaction comes in finishing four minutes straight of intricacy with a final exhale. We all feel the liberation—dancing as a unit makes us more ourselves. It’s even better when we put the costumes on: we wear servants’ clothes, and we put our aprons on to do the work but tear them off when we rebel against Mrs. Margaret. Barak makes sure that we throw them to the ground with enough fervor that the audience can read the subtext, which is effectively, “you b—-, I hate you.”

Important visitors

One very special evening, when we have learned the full excerpts, two special guests are wheeled into rehearsal. Barak pushes both his mother’s and his father’s wheelchairs. They are smiling ear to ear, and Mrs. Oved speaks softly and in a thick Israeli accent only Barak and his father can understand. He translates her English, but we’re still hanging on to every word, trying desperately to hear what they think about us. To us, they are legends: we’ve only heard Barak’s fond stories of them, of his childhood. Even now, he speaks of them in awe. Even when they’re in wheelchairs and he keeps his phone on ring in case something happens while we’re in rehearsal.

Celine Kiner and classmates in rehearsal with Barak Marshall for “Monger” at USC Kaufman (Photo by Carolyn DiLoreto/Courtesy of USC Kaufman)

Barak puts a small drum down in front of his mother and sits behind a larger one himself. She can’t walk, but she has not forgotten how to drum. He tears up as she sings, joining in for the chorus of an old Israeli folk song. Her voice is beautiful—even with the cracks of age, her renowned generosity prevails. Her smile is enough to make an audience sit for hours. Barak’s ties to tradition suddenly make sense. He is American, born and raised. He has no accent. But he is Israeli.

Mrs. Oved finishes her song, and we all applaud. Her smile somehow grows wider.

“My father is a singer,” Barak says, as though his mother isn’t. He counts his father in and a perfect harmony escapes both of their lips, as though they’ve been rehearsing for weeks. They haven’t—his father forgets the words halfway through the song, and Barak prompts him. I start crying when they return to unison.

We run our excerpts of Monger for them (our official performance is next week, so we’re focusing on the details now) and Barak’s mother asks if he can help her stand, just so that she can give us a standing ovation. I cry again. Barak looks at his mother as though she shaped the world with her own two hands, and we all believe it. Mrs. Oved looks back at him, and we know from her eyes that he has carried on her legacy just as she wanted. It kind of makes you wonder if she planned it all along.

The melody haunts my reverie

Right before the big performance, Barak catches me in the hallway doing what I do best: doubting myself. I probably don’t know the steps. I’m probably going to mess up the unison choreography and give myself away by being the only dancer that’s off the music. He sits down on the floor next to me.

“I’ve seen the way you carry yourself outside class,” he says. “You are articulate and you are unique. Promise me you’ll be that person on the stage. It’s not about the steps anymore. You have all that. Trust me, I’ve been watching rehearsals.”

Needless to say, I cry again, but not until after he has left. While he’s talking, I just nod and smile and manage to be my least articulate self.

By the time Barak sits down with me for his interview in the lobby, I already know exactly what I want to say about him. This interview is just for an article I’m writing for the school’s communications department. He keeps apologizing, telling me he’s a little frazzled today, that his mind is in a million places at once. Lately, he’s been spending his free time collecting audition postings for graduating seniors and pulling strings to get us into classes at companies where he has connections. He wants to make sure we end up in a healthy work environment, doing the best repertory in the world.

Despite the scattered mind, he is more articulate than most of the choreographers I’ve interviewed in the last four years, if not all of them. Not a single like or um escapes his mouth. Even if he wanted you to forget he was Harvard-educated, you couldn’t.

We finish the interview: all my questions are the same, and I’m worried I didn’t cover enough bases. The last question, the one I ad-lib, is what have you learned from the students during your residency? I ask all the artists this—you can tell when they’re making up their answers to seem humble. Barak’s answer is honest: we devour the choreography, and he feels like he has to keep up and give us more material. He respects us, he sees us occupying space as authors and not just dancers.

I decide that now is the time. I pull out a postcard I found in a museum when I studied abroad in Paris this summer, one I have been keeping in my backpack. It’s a Lichtenstein painting, with a lyric from a very special song that accompanies one of his pieces: the melody haunts my reverie, it reads. I bought it expressly for the purpose of thanking him, trying to explain what his piece means to me. Though it has been written for months, I have never found the right time to give it to him—he’s always surrounded with people. I’ve scrawled a few sentences on the back that are so sincere they could easily be bulls—, but he knows me well enough to read them accurately. He scans it in front of me while I pretend to occupy myself otherwise.

“This is why I teach,” he says. “You know that. Give me a hug.”

Written by Celine Kiner for LA Dance Chronicle, April 22, 2020.

To read Barak Marshall’s bio, click here.

To visit the USC Glorya Kaufman School of Dance, click here.

Featured image: USC Kaufman performance of Monger (Photo by Rose Eichenbaum/Courtesy of USC Kaufman)