With its track record producing Stephen Sondheim musicals and a nearly 50 year relationship with the late composer/lyricist, East West Players knows its Sondheim. Honoring that long and special connection, EWP closes its 2024 season with a new production of Pacific Overtures. The show runs from November 10 through December 1 at the David Henry Hwang Theater in Little Tokyo.

This is EWP’s third time with Pacific Overtures. The first was an offshoot of the original 1976 Broadway show. The second production in 1998 celebrated EWP’s move to its current mid-sized theater in Little Tokyo and was directed by then artistic director Tim Dang. As the show nears its 50th anniversary, current artistic director Lily Tung Crystal recruited Dang to return with a production that honors the original while injecting elements that bring the show into 2024. To accomplish that, the director brought in choreographers with skills in Broadway dance, Kabuki and fight direction.

When Pacific Overtures opened on Broadway, much of the largely Asian cast was drawn from East West Players. With music and lyrics by Sondheim, book by John Weidman, and directed by Hal Prince, the show garnered ten Tony nominations. It won for Florence Klotz’ kimono-influenced costumes, Boris Aronson’s lavish sets, and nabbed the Tony award for Best Musical. (A video of the Pacific Overtures performance at the 1976 Tony awards.)

The Broadway run lasted six months. LA first saw Pacific Overtures when the national tour came to the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion with those award-winning sets and costumes, and with much of the Broadway cast intact, including EWP’s founding artistic director and noted actor Mako in the pivotal role of the narrator.

Some critics and audiences struggled with the unfamiliar Kabuki style and Japanese cultural references that infused the show. Some reviews attached the dismissive label “concept musical.” Like many Sondheim shows, Pacific Overture’s brief Broadway run belied the long life that followed.

In 1978, Mako approached Sondheim to allow East West Players to present Pacific Overtures. Today EWP is regarded as the nation’s premier Asian American theater company, but in 1978, EWP was a young ensemble with a 99-seat black box theater in Silverlake, audaciously asking to take on a Tony-award winning Broadway show. Sondheim not only gave permission, but he also arranged for some of the Broadway sets to be given to EWP.

The production, with Mako directing, benefited from many of the original Broadway cast who had honed their portrayals on Broadway and during the national tour. Even without the elaborate trappings, and perhaps because of the more modest production values, the smaller venue allowed all of Sondheim’s artfully crafted and often profound lyrics to be clearly heard which crystallized the telling of the story. The venture was a success and established East West Players as a force in LA theater. Sondheim continued his support of East West Players. He joined the EWP advisory board, became a longtime donor, and periodically provided alternative lyrics to reflect the Asian casting as EWP went on to regularly include Sondheim shows.

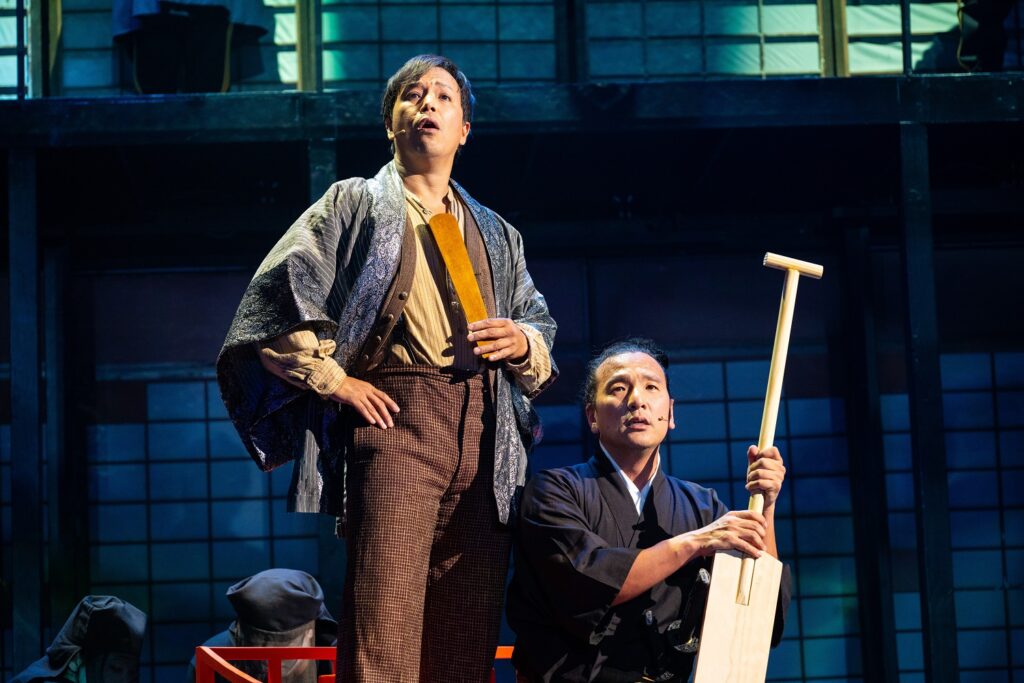

Kavin Panmeechao as the Physician, Gedde Watanabe as the Shogun’s Mother, Jon Jon Briones as the Shogun, and Kit DeZolt as the Shogun’s Wife performing “Chrysanthemum Tea” in Pacific Overtures. Photo by Teolindo.

At EWP alone, Dang has directed ten Sondheim shows including the 1998 Pacific Overtures. For this third revival, Dang assembled a cast that includes Jon Jon Briones from Broadway’s Hadestown in Mako’s role as the Reciter, and Gedde Watanabe who was in the original 1976 Broadway cast and continues the show’s legacy. In 1976, Watanabe’s roles included the “boy in a tree.” This time, Watanabe’s roles include that same boy as an old man. (A 1976 clip of Gedda Watanabe as the Young Boy in Someone in a Tree has Sondheim at the piano.)

Director Tim Dang spoke with writer Ann Haskins about the updated elements in the show, why he brought in three choreographers, and the long relationship with Sondheim. (The interview has been edited for length and clarity.)

Q: I understand that this production tweaks some aspects of Pacific Overtures to reflect the world of 2024, and also that the show’s writer, John Weidman aided that effort. In what ways?

Dang: Most of Pacific Overtures takes place in 1853 Japan, at the end of the Edo period, the time in the mini-series, Shogun. The final scene is the song “Next.” It does a quick progression, enumerating events and contributions that Japan has made to the world since opening to the West in 1853. The list in the song stops in the 1970s, when the show premiered. I wanted to bring that last scene into 2024. I advocated to John Weidman to add the baseball player Shohei Ohtani. He’s from Japan, the highest paid major league baseball player, hit this record of 50 home runs and 50 stolen bases, and then broke that new record.

We also discussed additions about Japanese manga and anime that are now international, and also additions about the gentrification facing LA’s Little Tokyo, as traditional mom and pop stores are being pushed out by higher rents. The inclusion of Little Tokyo is personal since East West Players’ theater is in Little Tokyo, but the issues have a larger relevance to the economic changes throughout LA and beyond.

Ashley En-fu Matthews, Gemma Pedersen, Sittichai Chaiyahat, Kit DeZolt, Gedde Watanabe, Brian Kim McCormick, Jon Jon Briones, Nina Kasuya, Kavin Panmeechao, Kurt Kanazawa, and Scott Keiji Takeda performing “Next.” in Pacific Overtures. Photo by Teolindo.

Q: Was it a coincidence that two of your choreographers echo the same type of exchange of western and Japanese cultures as the samurai and the fisherman in the show?

Dang: Yes. That wasn’t intentional, it just happened. Yuka Takara was born in Okinawa Japan, came to the U.S. and became a Broadway dancer, including a 2004 production of Pacific Overtures. Kirk Kanesaka was born in California, went to Japan to study Kabuki, and has become an honored figure in Kabuki theater and other Japanese arts. In the Kabuki world, he is known as Gankyō Nakamura, a name bestowed by the important Kabuki master he studied with. So yes, there are similarities with Yuka leaving Japan and coming to the American musical and Kirk leaving California for Japan and going deeply into Kabuki, just like the different directions taken by the Samurai and the fisherman.

There are actually three choreographers. Yuka comes with a musical theater background, which is really great, because there are portions of the show that require musical theater thinking. Kirk is the show’s Kabuki choreographer and consultant about everything from how someone in Japan wearing a kimono will enter a room, how they use a fan, and how they bow. It’s many of the cultural details that Kirk is taking care of and some of the vocal dictions of Kabuki. He also is involved in choreography for the song “There Is No Other Way” when the samarai has to leave his wife. That one is very Kabuki. The third choreographer, Amanda Noriko Newman, stages our fight scenes, teaches those in the fights how to take out a sword from the sheath, when to use the sword to slice or parry and how to do those moves. Once that is learned by the actors, Kirk comes back and will add certain things to the sword fight that are Kabuki style.

There is a lot of collaboration in other parts where Yuka sets the steps, and then Kirk will come in with touches that make it look as if done by a group of Japanese in 1853. As for me, I basically stage everything. Like a conductor overseeing the different sections of an orchestra. I’m thinking of where the lights will be and is it a spotlight, is it blue and on individuals or everyone? I’m thinking of how to stage it in terms of where people are positioned. Then once they’re positioned, Yuka or Kirk will give them the choreography or the actual movement to the piece. So it’s a real collaboration.

Adam Kaokept as Manjiro the fisherman (left) and Brian Kim McCormick as the samurai Kayama (right). Photo by Teolindo.

Q: Has the Kabuki movement posed challenges for the actors?

Dang: Yes, it has been a challenge. All of our actors have western theater training and many have danced, which is great, but no one except Kirk has training in Kabuki technique or Japanese dance. East West Players actually gave us an extra week of rehearsal so that we have time to begin to get into our bodies how to move with a lower center of gravity. A lot of our actors have had ballet training which wants the body to be up, up, up, but Japanese dance is down, down, down into the ground. There has to be learning of some new techniques that run counter to what dancers are usually told to do, like pull up when you dance, but instead learn to go into the earth. I’m originally from Hawaii and that grounded element is similar to the hula. Luckily, we have that extra week.

Also, we are bringing some Kabuki traditions into 2024. The Kabuki tradition is that men play both the male and female roles. We are having that as well as females play male and female roles in the show. Also, people might think of Kabuki as high art, the way many people think of opera. We give nods to contemporary anime and manga, which are also Japanese contributions to the to the arts. We hope adding anime and manga make the play more accessible to a younger audience who are interested in cosplay, going to Comic Con, and watching all the new anime cartoons on Netflix and Hulu. Those are some of the subtle differences that we are adding to the show, while still keeping in line with Sondheim’s original vision when the show first opened in 1976.

Sittichai Chaiyahat, Nina Kasuya, Aric Martin, Kit DeZolt, and Gemma Pedersen performing “Welcome to Kanagawa.” Photo by Teolindo.

Q: Did your involvement with Sondheim really begin as a dancer?

Dang: It did. I was a freshman theater major and despite rules against freshmen auditioning, I was a dancer and they were short on dancers. I was allowed to audition and so I was in the ensemble of Sondheim’s Follies. That show made me a fan.

Q: What was your first encounter with Pacific Overtures?

Dang: When Pacific Overtures opened on Broadway in 1976, I bought the cast recording. I was so impressed, I actually wrote to Stephen Sondheim at the age of 18, telling him how much I enjoyed the music of Pacific Overtures even though I hadn’t seen the play yet. Surprisingly enough, he wrote back to me. It was a very short note, something like ‘Tim, thank you so much for the compliments. I hope you get to see the show.’ And then signed, Stephen. He had a lot of fans, but he took time to write back to me.

Q: Would you talk about East West Players relationship with Sondheim?

Dang: Mako had already established an ongoing, active relationship by the time I joined the company. That continued when I became artistic director. When I was directing Sweeney Todd, I went to Stephen about lyrics referring to ‘yellow hair.’ As an Asian American cast doing Sweeney Todd, we did not have yellow hair. After a moment, Stephen said “Well, let’s see…yellow hair…yellow hair…How about raven hair?” And that was how it was sung. Stephen, and also the book writers, were very accommodating to what we were doing. Since he has passed, this production is my homage to him, a thank you for a long history with someone who I feel is America’s best musical theater composer.

East West Players – Pacific Overtures at David Henry Hwang Theatre in the Union Center for the Arts, 120 Judge John Aiso St., Little Tokyo; Thurs.-Fri. & Mon., 8 pm, Sat., 2 & 8 pm, Sun., 5 pm, thru Dec. 1; $15-$97. https://www.eastwestplayers.org/pacific24

The website has details on special events include:

Nov. 17-Pacific Overtures Alumni Night with EWP alumni from prior productions and a post-performance panel.

The Nov. 23, matinee with a pre-show panel with EWP’s current artistic director and a post-performance musical celebration dubbed Sondheim Night.

The Nov. 24 show has an ASL interpreter and a post-show Artist Talkback Panel.

Written by Ann Haskins for LA Dance Chronicle.

Featured image: Gemma Pedersen, Adam Kaokept, Nina Kasuya, Kit DeZolt, Gedde Watanabe, Kerry K. Carnahan, Kavin Panmeechao, and Scott Keiji Takeda in Pacific Overtures at East West Players. Photo by Teolindo.