San Francisco – Three years in the making, 12 headliners, and a cast of 80! No, not the latest movie blockbuster but San Francisco Ballet’s Unbound, the venerable company’s excursion into where ballet is at and where it might be going. The festival’s centerpiece is a three week swirl of a dozen new ballets performed until May 6. Surrounding the performances, the organizers’ kept an eye out for both ballet’s traditional audience and new viewers hopefully lured by videos, podcasts, interviews and other digital components that led up to the actual performances plus a symposium and other related events during the festival.

San Francisco Ballet in Christopher Wheeldon’s “Unbound” – Photo by Erik Tomasson.

Making its home in the white marble and gold gilt of the palatial War Memorial Opera House, the west coast’s oldest, largest and best funded ballet company, might seem a counterintuitive proponent of contemporary ballet. Known for its full length classics and 20th century masterworks from the likes of George Balanchine, Jerome Robbins and William Forsythe, San Francisco Ballet does present new contemporary ballets, usually a single one in a mixed bill program. Three weeks solely devoted to a dozen new, contemporary works is a major adventure for SFB, but not entirely without precedent.

Ten years ago, SFB hosted a smaller festival of new choreography modeled on similar festivals SFB’s artistic director Helgi Tomasson participated in as a dancer at New York City Ballet. High praise for the 2008 festival encouraged the company to have another go at it with this even larger effort.

San Francisco Ballet in Alonzo King’s “The Collective Agreement” – Photo by Erik Tomasson.

Of the twelve invited choreographers, only two choreographers, David Dawson and Cathy Marston, both well known in Europe, are completely new voices to both SFB and U.S. audiences. Christopher Wheeldon and Houston Ballet’s Stanton Welch were part of the 2008 festival. Justin Peck, Trey McIntyre, Ballet Met’s Edwaard Liang, Arthur Pita and SFB company member Miles Thatcher have created or set works on SFB before this. While new to SFB, the works of Dwight Rhoden and Alonzo King are well known to west coast audiences from their own companies, Complexions’ and SF’s Alonzo King Lines, and Annabelle Lopez Ochoa’s Requiem for a Rose was seen by Bay Area audiences last fall.

The choreographers were “unbound” in many respects but organizers provided some parameters. Each choreographer was assigned 24 dancers, each group included principals, soloists and corps. The 12 dancemakers were divided into four groups with the resulting programs, conveniently identified as A, B, C & D, presented in rotation over the three weeks. All used resident lighting designer James F. Ingalls, but otherwise were given an unfettered budget for costuming, set design, projections, and music choices.

Maria Kochetkova in Pita’s Björk Ballet. © Erik Tomasson

While the performance portion always occupied center stage, the lead up and surrounding activities were worthy of the opening of a new film.

During the intense weeks of choreography last fall, webcasts of rehearsal segments with choreographer and dancer interviews (https://www.sfballet.org/season/events/unbound-2018/unbound-live), four MTV worthy videos (https://www.sfballet.org/season/events/unbound-2018/dance-films-unbound), and other social media efforts were combined with community activities to widen the potential audience. More traditional audience members who sometimes balk at contemporary choreography were not forgotten. The impressive 75 page program includes extensive, almost overwhelming detail about each work including what to expect to see when the curtain goes up, paragraphs describing what each work is about, and profiles of each choreographer and the production team.

San Francisco Ballet’s Sean Orza and Max Cauthorn in Miles Thatcher’s “Otherness”. Photo by Erik Tomasson.

Every performance included SFB’s usual pre- or post-discussion panels. During the season, these usually feature a dancer, but for Unbound, most of the conversations strategically focused on a choreographer not in that particular performance. If overheard audience conversations were any indication, those pre-show comments stimulated interest in buying tickets to other shows to see that choreographer’s ballet. While the talks were limited to ticket holders, in another savvy move, the talks are part of a podcast series “Conversations on Dance” available to all. (Podcast information at https://www.sfballet.org/explore/podcasts.) Not surprisingly, SFB now also has a chatbot, a hashtag (#Unbound2018), and links to preview the music in the performances for the digitally inclined.

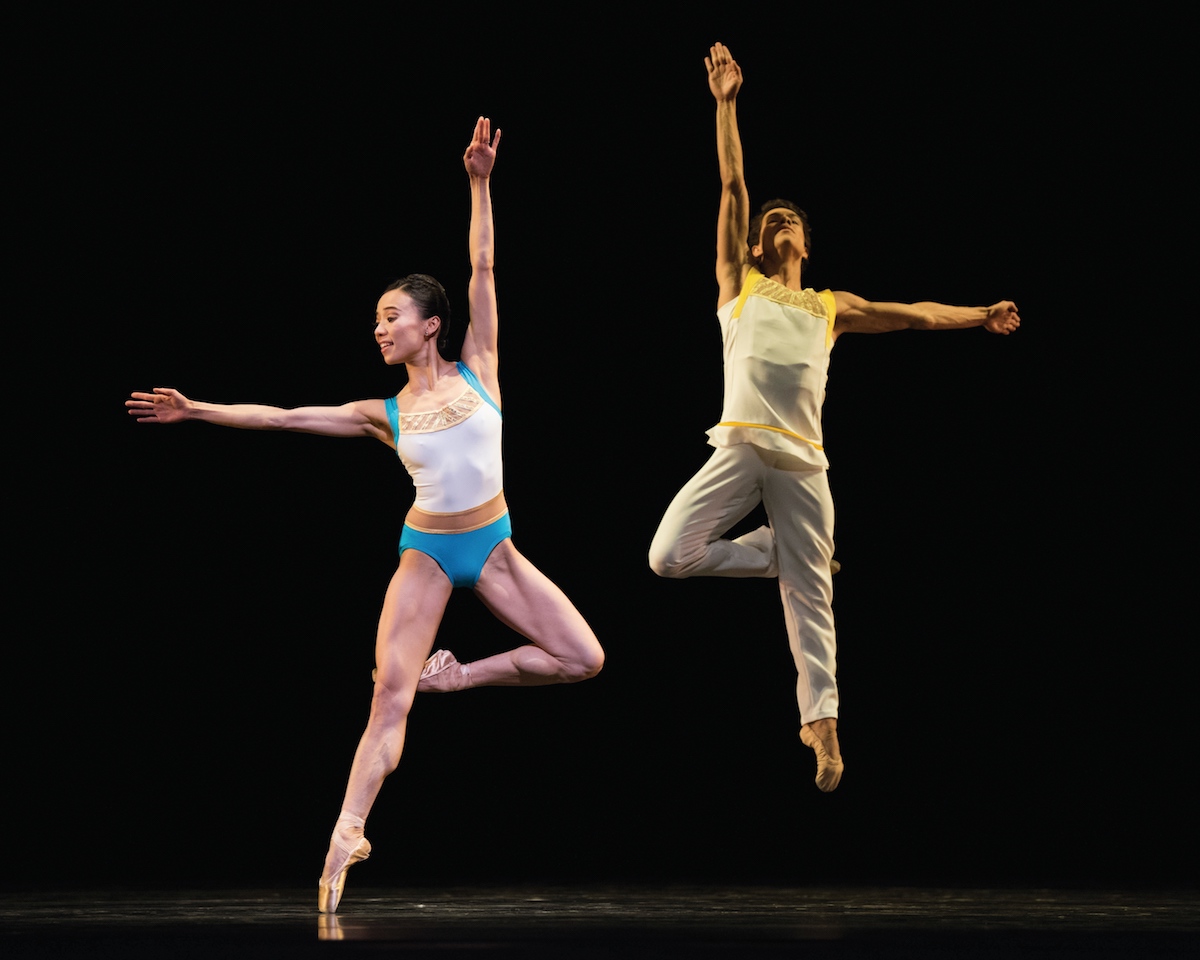

Frances Chung and Esteban Hernandez in Welch’s “Bespoke” – Photo: © Erik Tomasson

The first week of performances was a prelude to a three day symposium bringing together artists, scholars and critics to discuss how issues of choreography, diversity and technology are shaping and will shape ballet’s future. The symposium opening session was free, but the other three were ticketed and scheduled proximate to performances. Technology, racial and gender diversity were major symposium topics. Of the 12 participating choreographers, Lopez Ochoa, Marston, King and Rhoden provided the gender or racial diversity to the Unbound choreographer line up. As of this writing it was uncertain if the Symposium sessions will join the podcasts.

San Francisco Ballet in Marston’s “Snowblind” – Photo: © Erik Tomasson

And the 12 new ballets?

Program A eased audiences into the realm of contemporary ballet, opening with Alonzo King’s abstract The Collective Agreement with dancers in pointe shoes beneath rotating squares peppered with lights. A chuckle of recognition ran through the audience as the curtain opened on Christopher Wheeldon’s Bound To, revealing dancers staring at brightly lit cell phones. The eight episodes considered the isolation engendered by the allure of cell phones as well as the loss of human connection in episodes with projected titles that included “Remember When We Used to Talk” and “Remember When We Used to Play”. Despite those entreaties, as soon as the curtain went down, cell phones lit up throughout the audience. The soft ballet slippers in Wheeldon’s piece yielded to sneakers as Justin Peck’s Hurry Up, We’re Dreaming sent a gaggle of dancers jogging about and interacting like kids at a playground.

San Francisco Ballet in Justin Peck’s “Hurry Up, We’re Dreaming” – Photo: Erik Tomasson.

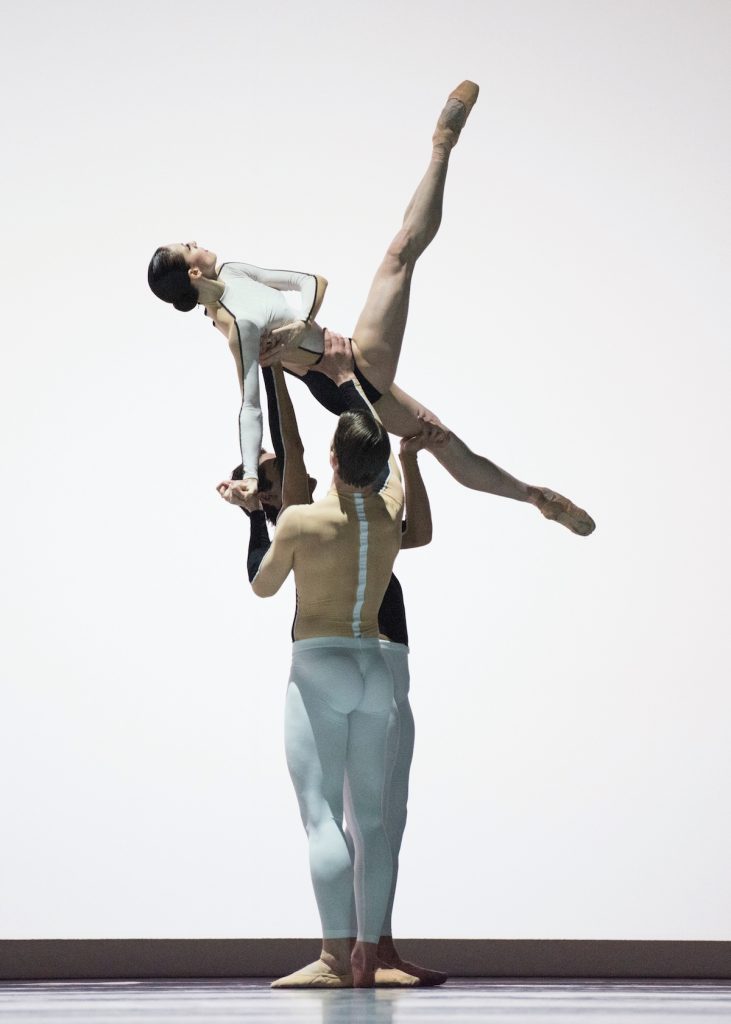

Program B opened with SFB company member Miles Thatcher’s Otherness, with two groups—one pink, one blue—each group in lockstep except for one misfit. Those two meet up and eventually reveal beneath the pinks and blues they all wore yellow. Cathy Marston’s Snowblind offered the clearest narrative ballet in the festival, a retelling of Edith Wharton’s Ethan Frome with the corps as a snowstorm that provides pivotal context for the tragic romantic triangle. Carl Jung’s concepts concerning male aspects of the female psyche and the female aspects of the male psyche were the starting point for serious ballet pyrotechnics in David Dawson’s abstract Anima Animus.

San Francisco Ballet in Dawson’s Anima Animus. Photo © Erik Tomasson

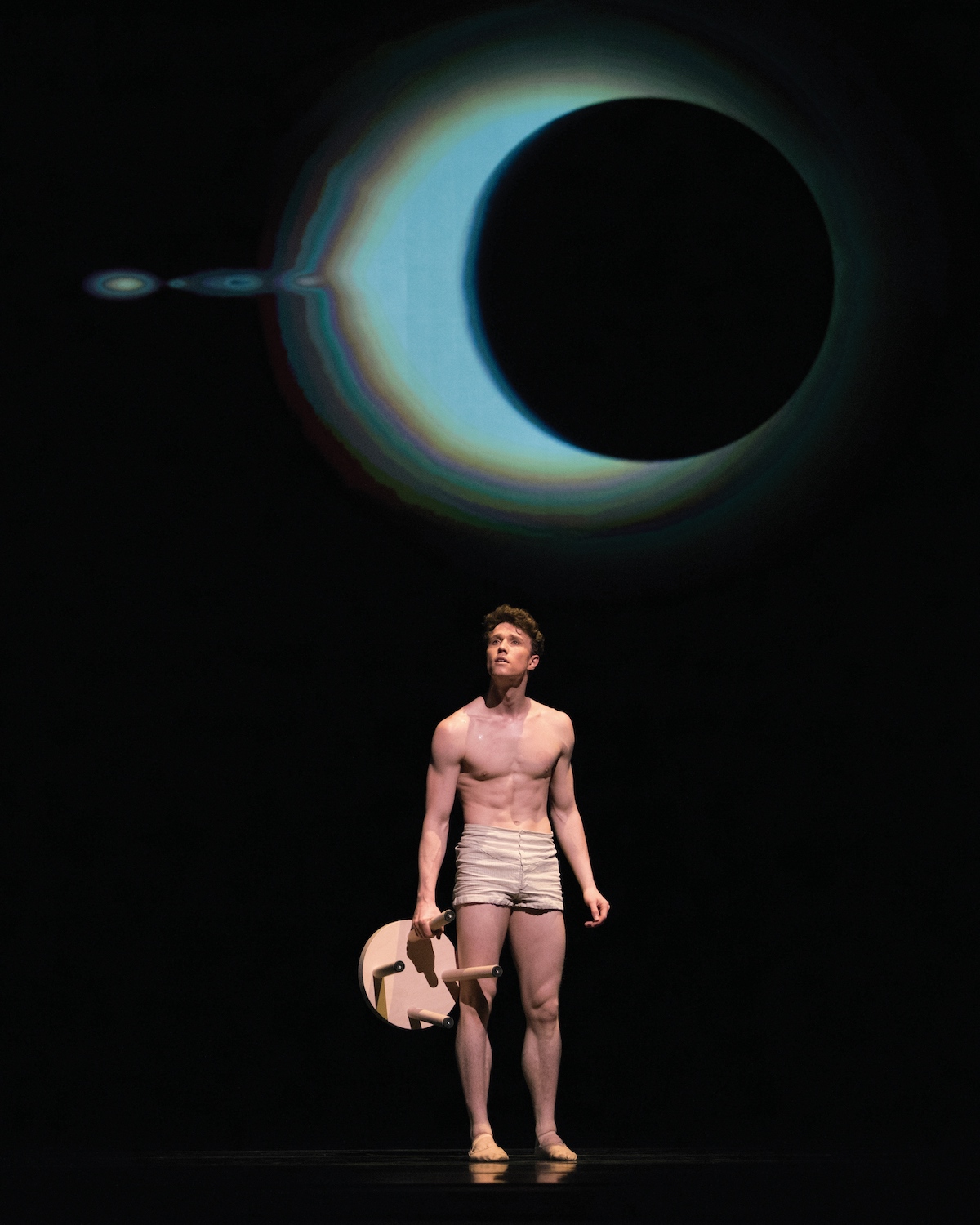

In Program C, Stanton Welch’s Bespoke paid homage to the dancers’ superb ballet technique and the brevity of a dancer’s career. Trey McIntyre’s Your Flesh Shall Be a Great Poem celebrated a grandfather he never actually met with the mostly male cast tearing up the stage beneath projections of last year’s solar eclipse. A blood-red backdrop and overt bullfighting references illuminated Annabelle Lopez Ochoa’s white hot tribute to Pablo Picasso’s Guernica with four suspended tubes spraying smoke on the dancers in a possible reference to chemical weapons now augmenting bombs in savaging civilian populations in war zones.

Benjamin Freemantle in McIntyre’s “Your Flesh Shall Be a Great Poem” – Photo: © Erik Tomasson

Program D may have offered the starkest contrasts. The starting point for Edwaard Liang’s The Infinite Ocean was the choreographer’s reflections on friends dying too young and confronting impending death, but the ultimately serene resignation provided a kind of comfort. Shifting to the opposite end of the intensity scale, Dwight Rhoden’s Let’s Begin At the End sent dancers ferociously spilling in and out of a wall with seven doors at an unrelenting pace. Arthur Pita’s Björk Ballet was perhaps the most anticipated and most divisive work in the festival. Riffing on Björk’s persona, Pita may have topped his over the top and off the wall version of Salome from last season. Employing nine of the popular Icelandic singer’s hits, advance publicity promised a rave. With dozens of glittery bushes descending from the rafters, multiple glittery costume changes complete with sequined Hannibal Lechter facemasks, and an endearing, roving clown, the goings on easily could compete with a Las Vegas edition of Cirque du Soleil. Since all 12 choreographers allegedly received the same budget, Pita seemed to have found a lot of discount sequins to underwrite the scale of the production elements which on first viewing tended to overwhelm the superb dancing going on. Audience comments afterwards reflected reactions severely divided between those who were thrilled and those who thought Beach Blanket Babylon did it better.

San Francisco Ballet in Rhoden’s “LET’S BEGIN AT THE END” – Photo © Erik Tomasson.

Based on Unbound, the state of contemporary ballet continues to defy precise definition much beyond something choreographed now and exhibiting one or more of a variety of trends that are too frequently ignored to be considered binding rules. A sure sign is an absence of tights on women and men frequently bare chested, allowing for deeper appreciation of the highly toned musculature at work. Don’t expect tutus, although Alonzo King’s The Collective Agreement garbed the corps in leotards with partial tutus, some feathered, some tulle and some resembling mini-versions of the Sydney Opera House. Pointe shoes appear as do soft ballet slippers, unless the piece is by Justin Peck, then don’t be surprised to see sneakers. A major factor remains the dancers who must be able to snap from traditional ballet pyrotechnics into moves once considered the exclusive realm of modern dance. As with more traditional ballet choreography, dancers of the high caliber found at San Francisco Ballet can elevate even mediocre choreography, whether classical or contemporary, by the sheer force of their dancing prowess.

San Francisco Ballet in Lopez Ochoa’s “Guernica” – Photo: © Erik Tomasson.

Could Los Angeles mount anything similar? Aside from San Francisco Ballet’s unparalleled financial support, several striking differences between the way dance is presented in Los Angeles and San Francisco make a similar SoCal festival doubtful, at least as things currently stand with L.A.’s dance diaspora and major SoCal venues dominated by touring companies.

San Francisco Ballet’s season runs roughly from December with the Nutcracker through the late spring. The opera season occupies the War Memorial Opera House in the fall, making that venue unavailable to the major national and international touring companies that in SoCal are the main dance series at the Los Angeles Music Center or Orange County’s Segerstrom Center for the Arts. Those touring companies generally don’t appear in San Francisco, but are presented across the Bay in UC Berkeley’s Zellerbach Hall, which offers less direct competition for San Francisco’s many dance companies. Also, San Francisco dance audiences are acclimated to several venues beyond the Opera House such as Yerba Buena Center for the Arts, ODC and Fort Mason’s Cowell Theater that regularly present local dance companies. With its major theaters committed to visiting companies, Los Angeles dance companies perform in venues spread all over L.A. sprawling metropolis, making dance harder for audiences to find. San Francisco is a concentrated city with SFB the major player, but the city’s audiences are primed for contemporary ballet by Alonzo King’s Lines and Smuin Contemporary Ballet as well as the modern dance companies such as Margaret Jenkins Dance Company and Brenda Way’s ODC.

San Francisco Ballet in Christopher Wheeldon’s “Bound To” – Photo: Erik Tomasson.

SoCal dance fans unable to get to San Francisco for the Unbound festival may well have more opportunities to see at least some of the new ballets. Reportedly a few of the 12 ballets will be included in the company’s fall tour to Washington D.C.’s Kennedy Center and the announced 2019 SFB season lists five slots for “new ballets to be announced”. Based on audience response and critics’ reviews, likely contenders to return are Marston’s Snowblind and Wheeldon’s cell phone ballet Bound To. With ballets set to popular music the ballet equivalent of a juke box musical, Pita’s Björk Ballet is almost a sure bet. Also, Helgi Tomasson is from Iceland and reportedly contacted Bjork when the choreographer encountered obstacles obtaining permission to use her music.

Many of the ballets presented in Unbound suggest an evolution more than a revolution in the art form, but far beyond the 12 ballets, the conversations started, and issues raised will continue to reverberate in the ballet world far beyond San Francisco, hopefully along with a chance to see these new creations in SoCal.

For more information on the San Francisco Ballet, click here.

Feature photo by Erik Tomasson.