Tetyana Martyanova is alone on stage. She stands with tension in her muscles until her back knee buckles. Her spine folds forward as she rebuilds her skeletal structure. She lands on an arabesque with her leg extended behind her. She turns slowly with so much control. She pushes the steps to its limits. After swinging her limbs in two-dimensional planes, she stretches further, arching her back and curving the position to break the two-dimensional mold. It is so entrancing that you do not realize Mike Nava’s artwork is changing behind her. She is magical. As the speed picks up, more dancers enter the stage. Soon, that magic fades in the flurry.

Raiford Rogers Modern Ballet’s performance at The Luckman on August 17 presented the world premiere of Glassworks alongside repertory pieces Études and Chanel. Together, the trio of works by Rogers revealed the evolution of his artistic voice that focuses on the embodiment of music. The pairings revealed a loss of specificity in his newer piece.

Glassworks includes an excess amount of movement and bodies on stage to highlight the music of Philip Glass, which is — for the most part — not as structurally overwhelming as the choreography depicts. As Martyanova’s solo revealed, less is more.

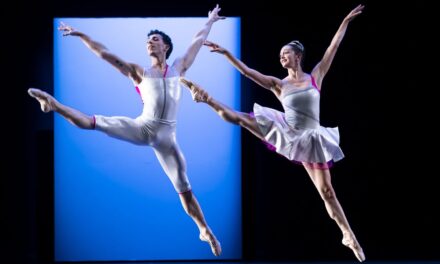

The new work incorporated a lot of Rogers’ signature beautiful movement. The vocabulary mixed swings and contractions, staples of modern dance techniques like Graham and Cunningham, with ballet. It is exciting to see how the choreography will use a swing of the arms to toss a dancer’s body into a polished pique.

But the overall use of space does not do the choreography justice.

The choreography includes plenty of canons. Groups of three or four enter the stage performing the same movement one second behind the other. Line formations create a ripple effect that is exciting to witness, but when there are three different lines and an additional clump of dancers, each performing different phrases, a lot gets lost. Instead of creating a tense feeling of contradiction that could replicate the music, it feels like nothing but a chaotic mess.

There is no value of space. Just as one group of dancers begins to fill the stage with energy, another group enters to rupture it. They are each fighting for attention. With so many bodies on stage, you could not tell which dancer was connected to which canon and the groupings became aspirational.

The steps tend to be staccato, but Gustavo Barros’ approach sticks out from the crowd. As he swings his arms over his head, he feels the stretch. It is like a yearning reach for something off-stage. Just when you are comfortable in the moment, he quickly snaps into the next move. His interpretation of the choreography was fully embodied, both physically and emotionally.

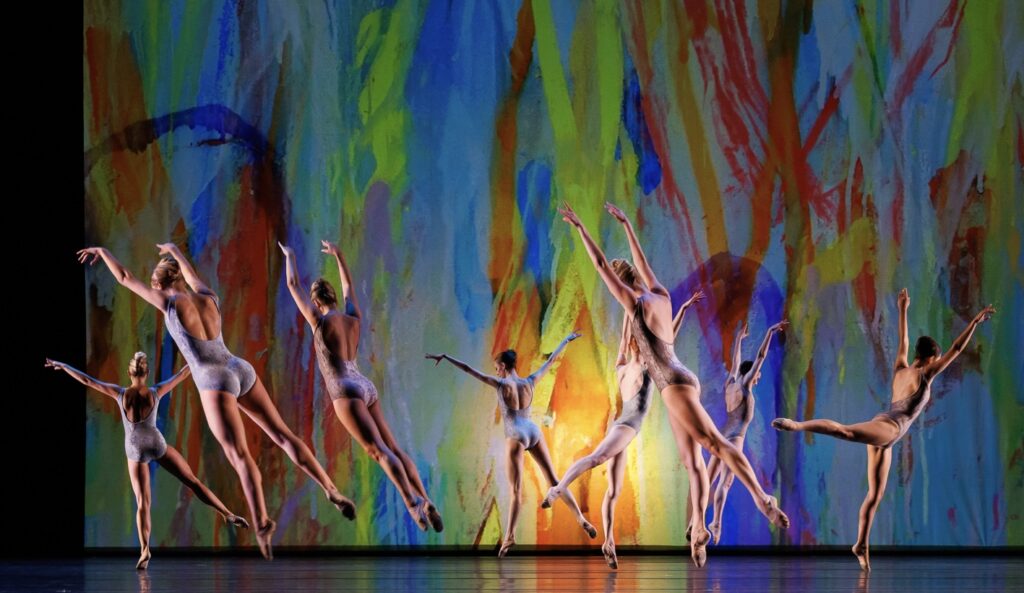

The work ends in a series of unified leaps with arms blossoming above the dancers. It is an incredible sense of relief. The choreography is suddenly visible. While it creates a satisfying release to see the dancers in unison for the first time in the piece, the satisfaction feels empty. Despite occasional moments of clarity, Glassworks is overwhelmed and overcapacity, making it difficult to discern any specific step or connection between sections. As a result, the great final sync in the choreography feels unwarranted.

Études, also paired with music by Philip Glass, found the sweet spot of movement and space. There are moments of chaos. For example, the company spread across the stage, moving from their spines and pelvis like seaweed or blades of grass at different tempos. These moments of chaos are short, yet powerful. Rogers’ connection to the music is much more visible this way. During Lucas Segovia’s solo, the piano flutters, and his hand swings behind him at the same time, highlighting the instrument’s presence in the piece. The piano comes to life with his body. Then when a new instrument plays, a large group of dancers turn and leap out of the wing. There is a strong conversation between the choreography and the music.

Études has similar canons and line formations but are used more intentionally than in Glassworks. There is more space between sections, allowing for the choreography to be seen clearly.

The program concluded with Chanel, a short piece from 2002 with music by Amon Tobin. It is drastically different from Rogers’ newer works. Women in the company stayed in one formation on stage, moving in slow motion between poses and steps. It felt like a class exercise, but not in a bad way. It allowed the audience to witness the process and attention to detail that Rogers has. You see them slowly lower their hands and roll up their spine together. After spending most of the program seeing everyone scattered, this moment of complete unison stands out.

As the women exit the stage, the flurry is forgotten. The moments of clarity in the choreography stick out a bit more, but they also remind us that so much of this gorgeous movement was lost in the chaos.

For more information about Raiford Rogers Modern Ballet, please visit their website.

Written by Steven Vargas for LA Dance Chronicle.

Featured image: Lillian Fife, Joshua Brown, Cassidy Cocke in Raiford Rogers’ Études– Photo by A. Trelease.