An evening in two acts: Act 1 – Play with us

Act II – Watch us Play

Act I, “Play with us” offered the audience three options of interaction with “Bodies in Play.” The first option was Room 1 where two of the performers took the audience participants through some movement with ‘no experience required’. The second option was Room 2, where three of the performers from the group led the audience participants to ‘contemplate identity’, ‘meet someone new’ and ‘celebrate yourself’. The third option was Room 3, or the lobby, where one could read the performers’ responses to the prompt. “What is Play?,” and also write one’s own thoughts about it on a large white board provided for the exercise. That was fun.

Bodies in Play – Act I of “Our Dancer’s Project” directed by Andrew Pearson – Photo: Winnie Mu @winniemuvisuals.

Act II: “Watch us play” was where the audience entered the performance space proper and sat to watch what was to have been ostensibly a dance show. I need to say here that this show has put me in an awkward position. Much of the show was geared towards listening to the dancers tell stories of how they were demeaned, insulted and/or abused during various episodes in their dance training and careers. Many of the instances related had to do with choreographers and directors criticizing and judging these dancers by body type and physicality. These stories were meant to mimic the stories that were relayed in the original Dancer’s Project of 1974 which later became the basis for “A Chorus Line”. More on that later. I was asked to attend the show as a critic – yet the very definition of criticism according to the performers present was one of insensitivity and abuse. Moving forward I will attempt to do my job while walking that razor’s edge.

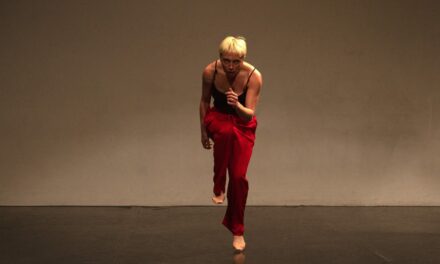

Bodies in Play – Daurin Tavares in Act II of “Our Dancer’s Project” directed by Andrew Pearson – Photo: Winnie Mu @winniemuvisuals.

That being said, the show opened with a voice-over on the microphone from Andrew Pearson. This preamble to the show began as a litany of how dance for him, producing and choreographing shows, is not a business that makes him any money. He goes on at great length to say that all of his shows have been in the red. He has produced nine shows in the last twelve years and every time he ‘wants to quit dancing’ afterward. He details how wearing the many hats to produce, choreograph, direct, and raise money for his shows exhausts him and is a thankless task. All of which is true for anyone who has self-produced in Los Angeles in particular, and in the U.S. in general. I have self-produced shows of my own and agree with him. However, to regale an audience with all of the negative aspects of putting on a show while they just paid to see this one seems in bad taste. It was at this point that a man next to me said, “This isn’t playful, this is sad.”

Bodies in Play – Celine Kiner in Act II of “Our Dancer’s Project” directed by Andrew Pearson – Photo: Winnie Mu @winniemuvisuals.

Pearson then alludes to a group of dancers who, in 1974 took matters into their own hands and began a group meeting which would be called “The Dancer’s Project”. A choreographer/director was invited to those meetings, one Michael Bennett, who then went on to turn those meetings into “A Chorus Line.” Pearson details how Bennett took control of the project and ultimately cut the dancers out of the creative process. Pearson’s show, at least the second act of it, is his homage to “The Dancer’s Project.” Only this time, ALL the credit and budget would go to the dancers instead of Pearson himself as ‘Creative Director.’ During the evening he continues sporadically to compare himself favorably with the unfavorable character of Michael Bennett.

Pearson ends his opening speech with the admonition that just like the original dancers in “The Dancer’s Project,” ‘We are not here to dance, we are here to talk.’ And for the rest of the evening that proved true. There was a microphone set up on each side of the space with a stand next to each holding the journals of the dancers speaking. As a dance critic, I did not have much to go on. There were a few exercises in movement made in tableau, and there was one sensual duet to a soulful jazz tune that was good.

Bodies in Play – (L-R) Rachel Whiting, Darby Epperson, Sadie Yarrington, Cristina Florez, Daurin Tavares, Tiffany Sweat in Act II of “Our Dancer’s Project” – Photo Winnie Mu @winniemuvisuals.

One of the themes of the evenings recitations was the realization that being a dancer is tough, and subjecting oneself to the mean-spirited scrutiny of auditions and physical criteria is synonymous with accepting abuse. Many had quit dancing, only to return a while later out of the love for the artform. Pearson himself had said that he wanted to quit dancing after every show and yet was still at it twelve years later. Why? Because, like the song from the show ‘What I did for love,’ he loves the artform. This show was Andrew Pearson rising above the selfish example of Michael Bennett and giving his dancers due credit and voice in telling their stories and creating their own movement such as it was.

Bodies in Play – (L-R) Cristina Florez and Daurin Tavares in Act II of “Our Dancer’s Project” – Photo Winnie Mu @winniemuvisuals.

Pearson mentions the possibility of Bennett being ‘a genius’ which could or could not excuse Bennett’s manipulative and demeaning behavior towards his dancers. One performer asks: “Do I accept the abuse, or do I quit dance?” I have never worked with Michael Bennett so I cannot comment on his character, but I do know that not all choreographers are insulting and abusive. Not all directors are power hungry egotists. Most have a strong vision that they want realized through the artform of dance, including music and costume, acting and physicality. Of course, they can be specific and demanding, that is what dancing is: demanding in every sense of the word. It is an over-simplification to form the entirety of Dance as an artform in terms of a necessary decision to quit dance or learn how to be fine with suffering abuse. Any athlete has the same decision. There are injuries and the pushing of physical limits, and a mental attitude that must navigate setbacks and intense pressures. This difficult path is not for everyone.

Bodies in Play – (L-R) Rachel Whiting, Sadie Yarrington, Daurin Tavares in Act II of “Our Dancer’s Project” – Photo Winnie Mu @winniemuvisuals.

In the program notes Pearson states that he got his biographical and historical information about Michael Bennett and ‘A Chorus Line’ from the book: “On The Line: The creation of A Chorus Line,” published in January of 1990. The vilification of Michael Bennett stems from this book. Had Pearson dug just a little bit deeper he would have found a different take on Bennett’s character and his role in creating ‘A Chorus Line.’ I am referring to the tell-all book that came out before “On The Line.” This book is: “What They Did For Love – The Untold Story Behind the Making of A Chorus Line,” published June 1st, 1989. I would recommend not being so ready to disparage another choreographers’ character, especially a choreographer/director of Michael Bennett’s caliber based on one literary reference. At least cross reference with other sources in order to gain a more complete picture of events.

Bodies in Play – (L-R) Cristina Florez, Darby Epperson, Celine Kiner, Daurin Tavares, Tiffany Sweat, Sadie Yarrington, Rachel Whiting in Act II of “Our Dancer’s Project – Photo: Winnie Mu @winniemuvisuals.

By the end of the show it was apparent that Pearson created “Our Dancer’s Project” with the other dancers involved in order make a statement about his own moral rectitude and to show the audience that he is of a more honest character than Michael Bennett who became rich off of the life stories of others. It is written in the program and was also stated over the microphone that all of the writing and all of the choreography was created by the dancers. It was in this way that Pearson handed over the ownership and control of the work to the dancers responsible for it – so unlike the cruel, manipulative and abusive Michael Bennett.

Bodies in Play – (L-R) Celine Kiner, Cristina Florez, Daurin Tavares, Rachel Whiting, Darby Epperson, Andrew Pearson in Act II of “Our Dancer’s Project” – Photo Winnie Mu @winniemuvisuals.

The dancers in “Our Dancer’s Project”: Cristina Florez, Darby Epperson, Celine Kiner, Tiffany Sweat, Daurin Tavares, Rachel Whiting, Sadie Yarrington, with additional writing by Andrew Pearson.

What was not mentioned or addressed was the particular position that Michael Bennett was in that got the Dancer’s Project noticed and taken seriously. Bennett had always wanted to do a show about dancers and had his eyes and ears open for just such a project. Also missing from Pearson’s Dancer’s Project was dancing, singing, and acting. Everything that went into making “A Chorus Line” so emotionally powerful was missing. This was even acknowledged by Pearson himself at the bows when he said to the audience that his show would not be remembered or made into a movie. The many negative accounts and stories that were told throughout the evening that were supposed to make us feel sympathy and empathy for the dancers’ struggles to continue in the work they loved, only served to render the audience participants in a group therapy that was not an entertainment.

For more information about Andrew Pearson and Bodies in Play, please visit their website.

Written by Brian Fretté for LA Dance Chronicle.

Featured image. Bodies in Play – (Top to Bottom) Rachel Whiting, Daurin Tavares, Cristina Florez in Act II of “Our Dancer’s Project” – Photo: Winnie Mu @winniemuvisuals.