Born amid the human and physical debris of World War I, Bauhaus is widely hailed as an influential school of architecture and design, but it was much more. Opened in 1919, the school’s approach blended elements of architecture, fine arts and crafts into gesamtkunstwerk (a total work of art) what might now be described as holistic. An often-overlooked facet of Bauhaus is the part dance played in its curriculum and later on, the role of dance in Bauhaus’ survival when under siege by the Nazis.

For what turns out to be its debut exhibition, the Getty’s Research Institute provides a two-part deep dive into the world of Bauhaus. A physical exhibition Bauhaus Beginnings runs to October 13 at the Getty Center along with a three-part, on-line exhibition Bauhaus Building the New Artist that offers a chance to participate in Bauhaus-style endeavors.

Among its efforts to rebuild a devastated Germany after WWI, the Weimar government funded Bauhaus’ innovative approach with a rigorous curriculum of wide-ranging studies taken by all students before they could specialize in architecture, visual art, dance, or weaving. Although some women successfully resisted, after the broad initial studies, most women students were pressured into the weaving major, but more on that later.

As Hitler and the Nazi party consolidated control of the German government, they attacked Bauhaus as degenerate. Fueled by nationalism and nostalgia, Nazism ran counter to Bauhaus’ international and avant garde approach, and then there was a significant presence of Jews among the faculty and students. While many stayed and persevered, many notable faculty emigrated to the U.S. and other parts of Europe. Rather than stifling Bauhaus’ influence, Hitler generated a Bauhaus diaspora, its influence taking root in America, particularly in architecture and fine art, but also in furniture, pottery and dance.

Those who remained faced the end of government financial support and growing Nazi hostility. Left with funding only from limited student fees, Bauhaus found that dance and weaving could keep the doors open. Dance performances with innovative costumes and concepts brought in ticket sales and the woven products (from those women students pressured into weaving) also became big sellers. Originally developed as one of a kind, the profitability of the woven patterns prompted Bauhaus to develop if not mass production, multiple production of its popular designs.

The physical component of the exhibition at the Getty Center surveys Bauhaus’ founding, development, and far-reaching influence with displays and photos particularly deep on the curriculum’s creative use of diverse media by the students. The exhibition draws on the Getty’s own extensive collection of Bauhaus material as well as loans of prints, drawings and photographs, many seldom seen at all and never in this organized format.

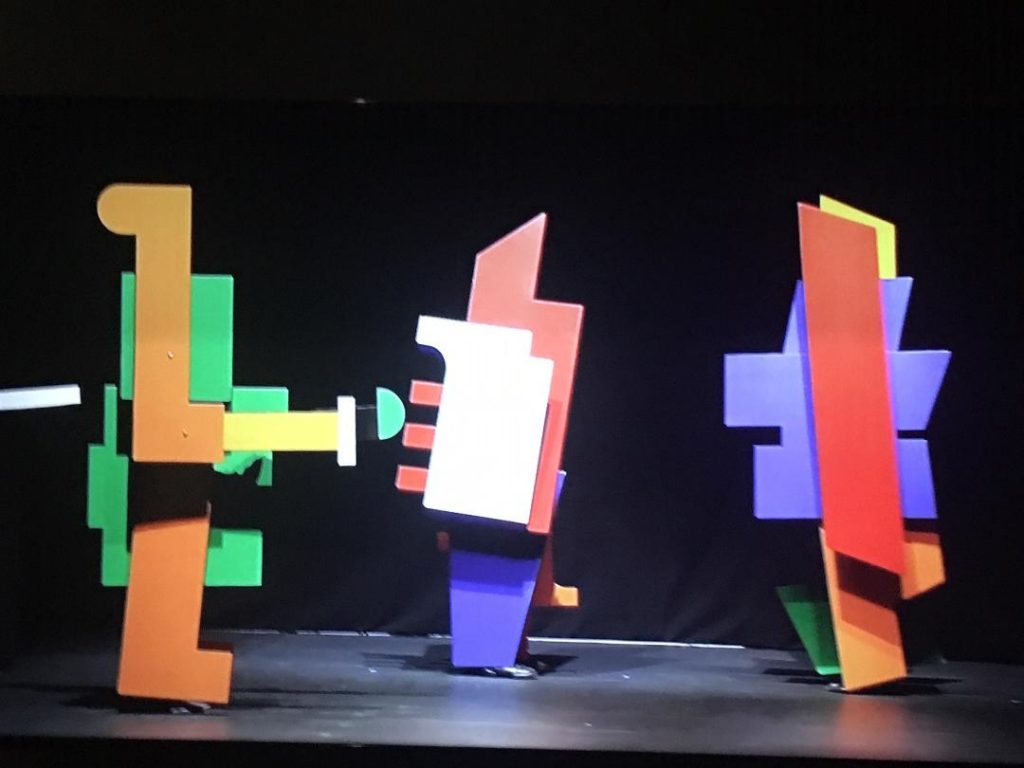

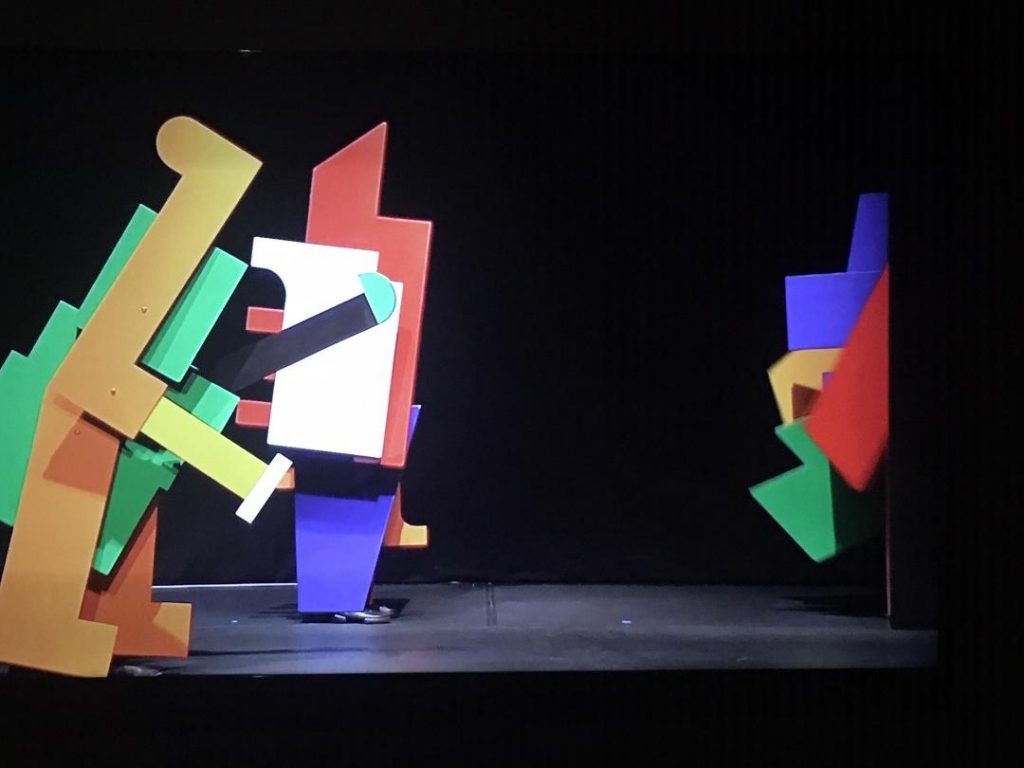

Dance fans should seek out the darkened alcove with photos, programs, and other memorabilia. Videos of recreated Bauhaus dance performances reveal how the integration of craft and fine art were captured in movement. In one video a blue clad dancer spins slowly, making a circle herself and simultaneously circling gradually outward from the center along a spiral marked on the floor. Another video captures a colorfully clad trio who take turns in puppet-like choreography.

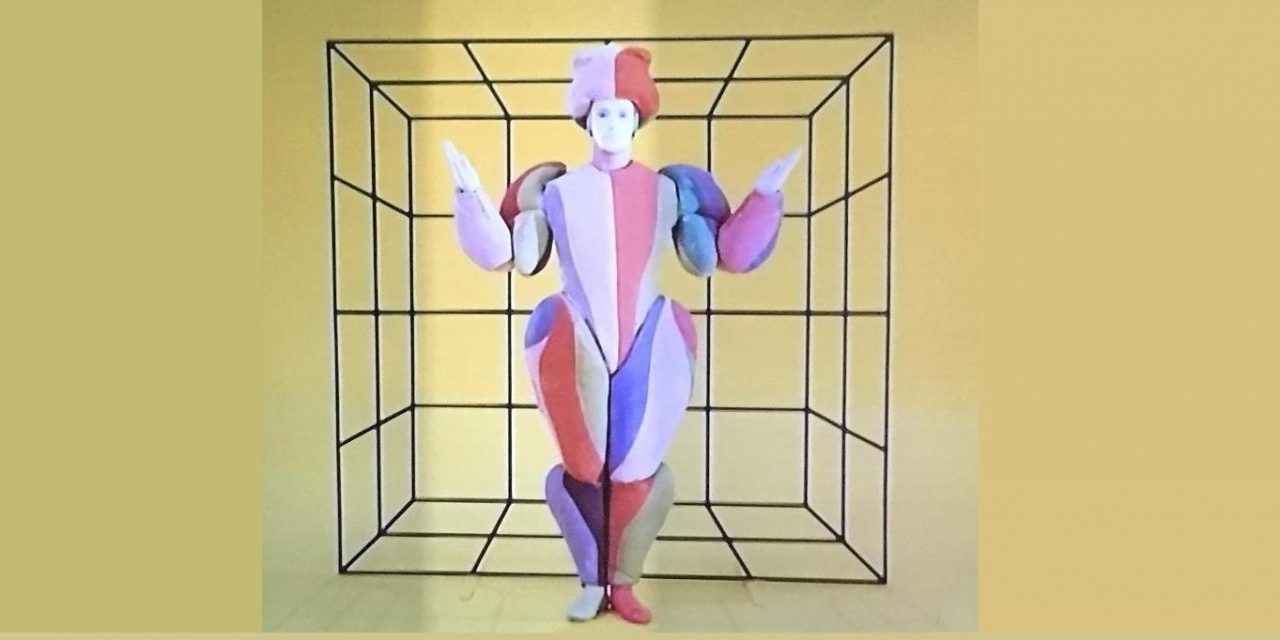

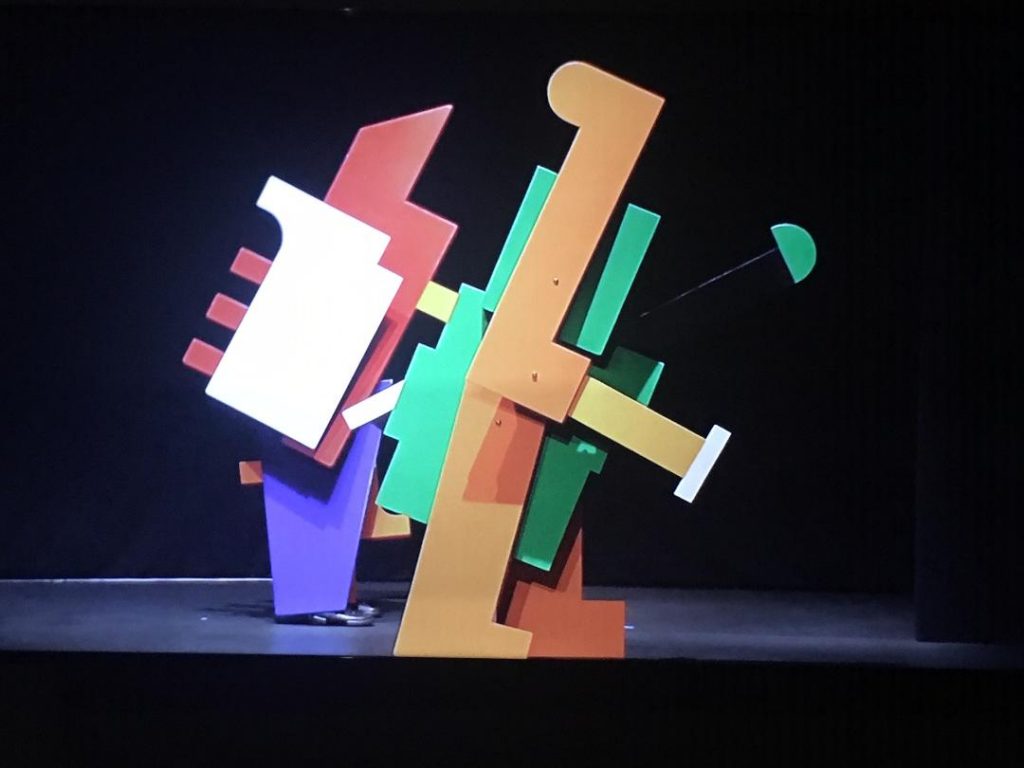

A third video captures bodies disguised by colorful geometric shapes that move like multi-colored Lego blocks being assembled and reassembled in stop motion animation, the appearance is non-human except for an occasional glimpse of shoe. Mostly created in the 1920’s, the movement admittedly is dated, but for its time was considered experimental. The costumes are reminiscent of Pablo Picasso’s creations for the 1917 Ballet Russe’s ballet Parade and even today could appear as part of the popular Swiss human puppet troupe Mummenschanz.

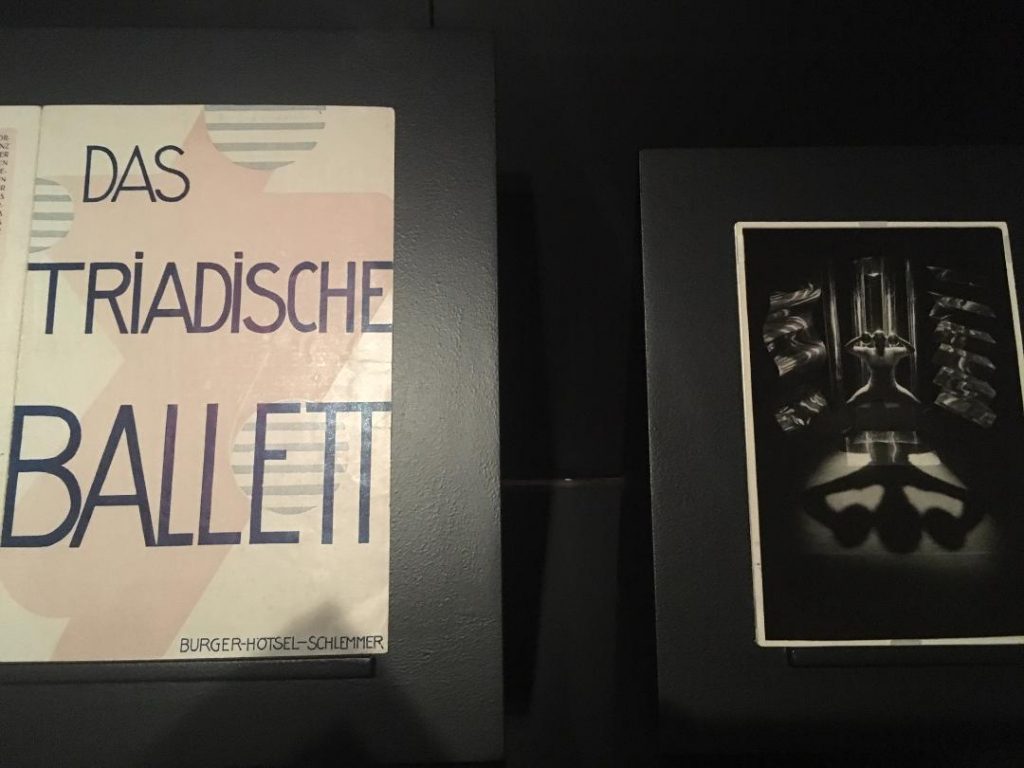

The on-line exhibition offers three interactive modules that offer Bauhaus-style engagement exercises in art, architecture and dance. In the dance component, after viewing a clip of Oskar Schlemmer’s The Triadic Ballet, the viewer acts as choreographer choosing among three different types of movement, three different costumes, three types of music. The animated end result is performed and can be altered multiple times. The art component focuses on a Vassily Kandinsky “form and color” exercise and the architecture portion requires scissors in a Josef Albers cutting exercise to create a 3-dimensional design.

Poster for and performance photo from Oskar Schlemmer’s “The Triadic Ballet”. Photo courtesy of the Getty Institute.

While ultimately the school closed and Bauhaus figures were among the Nazi victims, ironically instead of Bauhaus’ destruction the Nazi persecution inadvertently propelled its influence. Those who left carried Bauhaus with them to other parts of Europe and to the U.S. where Bauhaus concepts and approaches were transplanted and flourished. The exhibit includes a section on the Bauhaus diaspora which has a dance element in North Carolina’s Black Mountain College where major Bauhaus figures were faculty whose students included Merce Cunningham, John Cage, Buckminster Fuller, Franz Kline, Willem and Elaine de Kooning. The college closed in 1957, but a book in the museum store recounts its history and how the founder’s ideas on progressive education fused with the Bauhaus philosophy.

Bauhaus Beginnings Getty Center, 1200 Getty Center Dr., Brentwood; thru October 13, 2019, Tues.-Fri., Sun., 10 a.m. – 5:30 p.m., Sat., 10 a.m. -10 p.m., free, parking price varies. http://www.getty.edu/. Bauhaus Building the New Artist- online exhibition www.getty.edu/bauhaus.