“When you think about Black movement, it’s always thought of as essential, but collaborative.”

Tyree Boyd-Pates, historian and curator of The Ford’s Movement/Matters virtual program, opens each of the program’s six video segments with this statement. Boyd-Pates’ thorough curational study on Black movement and intertwined Black art forms digs deep with some of the community’s most respected pioneers. The program features both a fresh and intersectional perspective for the expert audience and a candid accessibility for folks new to the scene.

Boyd-Pates’ programming explored 50 years of Black movement indigenous to Los Angeles, beginning with the alumni of Soul Train. Panel moderator Flo S. Jenkins, former editor of Right On! Magazine, interviewed dancers Thelma Davis-Martin, James “Skeeter Rabbit” Higgins, and Damita Jo Freeman on the show’s role in bringing Black movement and Black culture to the forefront of the American screen. Soul Train set into motion a cultural shift that still moves today, centering Black social dance for the public eye and spotlighting it in mainstream media.

“The first day… I went on Soul Train, I got a chance to see how everything around Soul Train was Black. Black people, Black kids, Black camera men…Black everything,” Freeman said. “Because I was coming from a world of ballet, and being in the ballet world, everything was always white…But this time, I walked into a mesmerizing thing.”

Davis-Martin echoed the sentiment, sharing how special it was to be part of a community where the decision-makers were Black, where Blackness was celebrated, and Higgins explained the camaraderie that developed over late nights on set, dancing through countless takes. The dancers explained how they also bonded with the show’s musical guests, who saw that because of a shared vocabulary, the Soul Train dancers translated the depth and quality of Black music for the viewing public.

“When the artists came, there was no separation. You could see that they were from the same culture. They really appreciated us exhibiting their music the way their music should’ve been exhibited…they were seeing the real funk and soul that was coming out of it,” Higgins said.

The panel discussed that as Black culture came to the forefront and was celebrated on national media, it was appropriated for white mainstream media – trailblazers like Freeman, Higgins, and Davis-Martin weren’t fairly credited for their work, their culture, their creativity. Often, blockbusters like Saturday Night Fever presented Black dance on white bodies, asserting the movements as their own. But these pioneers – the panelists and their colleagues – would set the stage for generations of American movement, art, and culture to come. Though they and many of their contemporaries would be invisibilized as the nation fell in love with soul and funk (and Blackness itself), their contribution to American culture is boundless, and it continues to manifest in the circulation of Black social dances today. You may see them in the form of TikTok dances, music video crazes, and even in iconic steps that evolve throughout the years – including the Skeeter Rabbit, which is named after Higgins himself.

“It is not just about us. It is about a community of African Americans, Black and Brown, that emphasized what took place during that era, and still takes place today, how important it is,” Higgins said.

This sentiment rings true for the many iterations of Black dance communities that appeared in Los Angeles in the following decades. Boyd-Pates’ curation explores Black movement in this light, celebrating its brilliance, acceptance, community as it wrestles oppression.

In the festival’s 1980s: Voguing and West Coast Ballroom segment, Cuauhtemoc Peranda (Overall Prince DonTé Lauren of The Legendary House of Lauren, International) and the Legendary Sean/MilanTM (one of the co-founders of West Coast Ballroom Scene, producer of the Ovahness Ball, and creator of The House of AWT) discussed the establishment of houses in Los Angeles, acknowledging the Black and Brown, queer and trans founders of the scene who formed houses as a space for chosen family. While the Ballroom scene is known for its expansive inclusivity even today, houses were rooted in sanctuary, creating a place for Black and Brown, queer and trans folks to express themselves freely and safely.

“Bringing visibility to Ballroom, bringing visibility to the talent of Black and Brown folks, especially LGBTQIA+ artists, is very, very important,” Sean/MilanTM said.

Jackie Lopez (aka Miss Funk) – Rennie Harris Puremovement – Rennie Harris Funkedfied – Photo courtesy of the Ford Theatres

Boyd-Pates then dives into the links between Clowning in the 1990s and Krumping in the 2000s, celebrating the haven that Tommy the Clown’s Battlezone brought to 1992 Los Angeles amid the Rodney King riots, and locating the branching of more rugged Krump styling from the same community. He and Tommy the Clown spoke on the importance of mentorship:

“You made it a safe place for Black kids, particularly in South L.A., to come and not only just compete, but also to see the beauty of the community,” he said.

The 2000s installment sees the development of Krumping through the eyes of Versa-Style Co-Founder and Artistic Director Jackie Lopez, as well as Versa-Style member Brandon Allen “BeastBoi” Juezan-Williams.

“It brings healing, it brings empowerment. It [gave] me a place in the world when I felt very, very confused,” Lopez explained, sharing her own history with hip-hop and street dance but also recounting Juezan-Williams’ discovery of Krump as a young dancer, and the way it changed his outlook on life. His deliberate, convicted movement in the dance film that follows – Versa-Style’s “Powers That Be” – proves just how affecting the movement is in his body.

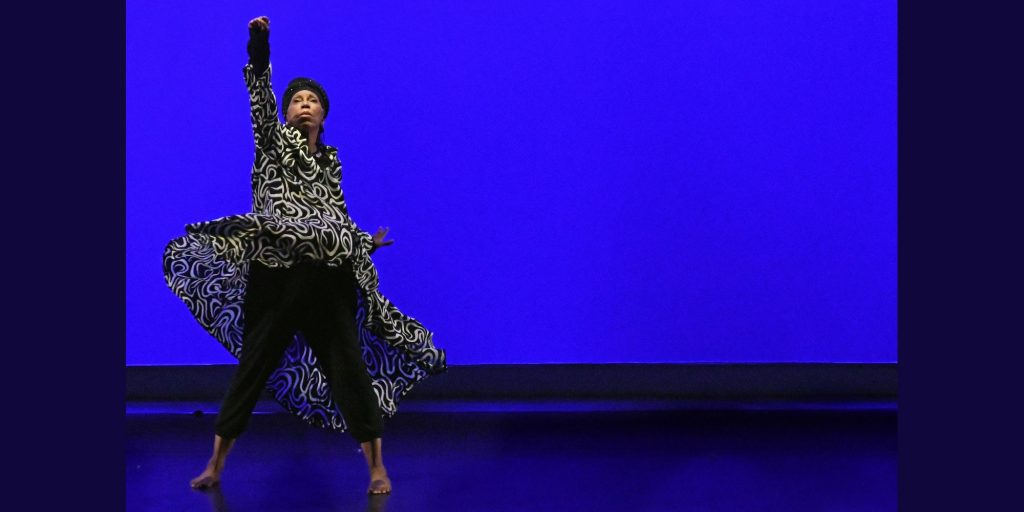

Lula Washington Dance Theatre performs the world premiere of “To Lula with Love/Warrior” by Christopher Huggins, featuring Lula Washington (pictured) at the Wallis Annenberg Center for the Performing Arts on January 30, 2020 – Photo by Kevin Parry

The video installments wrap with Dr. Shamel Bell on the origins of Black Lives Matter and her work with Street Dance Activism in the 2010s, and a retrospective on 40 years of the community’s beloved Lula Washington Dance Theatre in 2020. There’s a resounding understanding of the social statement that comes from Black dance, the expression of living itself that movement allows for Black and Brown bodies.

“Dance and joy is our resistance,” Bell shared. “Living is resisting.” Her recent global dance meditation has spread worldwide from Los Angeles, bringing relief and community to movers everywhere.

This virtual gathering of Black movement is an abundant resource as well as a glorious assembly of meaningful work. Boyd-Pates includes playlists of essential tracks from the progression of Black movement, ranging from Kool & The Gang’s “Get Down On It” to Kendrick Lamar’s “Alright” – and don’t miss out on the specialized playlists for the Soul Train and Vogue eras. He’s also provided viewing and literary resources for ancillary learning, and spotlighted Black-owned businesses you can support throughout the festival (or any time of the year). There’s enough material to sustain you for weeks. Don’t miss it; you can watch all six installments now, on The Ford’s website

Written by Celine Kiner for LA Dance Chronicle.

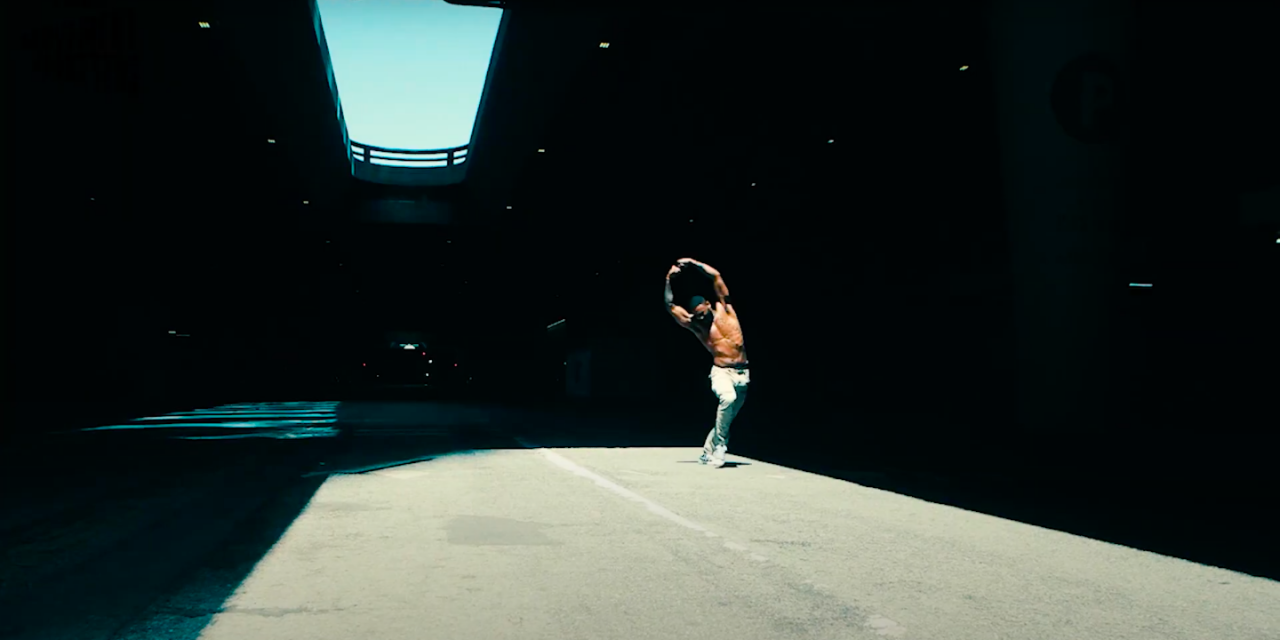

Featured image: Jo’Artis “Big Mijo” Ratti – Screenshot from film “Hold On”.