On Saturday, September 30, after a flurry of audience members attempting to get to their seats on time, it began! 8:00 Sharp, lights dimmed at The Saroya. It was the first night of The Martha Graham Dance Company’s (MGDC) centenary celebration. Thor Steingraber, Saroya’s adroit Executive and Artistic Director walked onstage. He welcomed all and introduced the Graham Company’s Artistic Director, Janet Eilber, MGDC’s tireless leader. Eilber presented an overview and introduction, with a bonus. Because of “Martha’s” extensive body of work (181 dances), it was decided that it was to be a three-year celebration. It would include not only Graham’s work but also a number of artists/innovators connected with her in those memorable beginnings of Modern Dance.

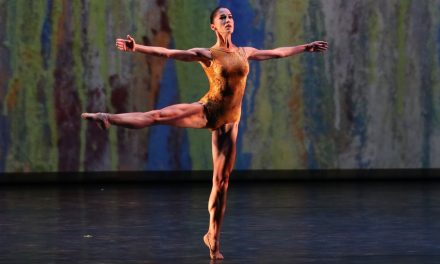

Marzia Memoli in Ted Shawn’s “Serenata Morisca,” performed in the world premiere of GRAHAM100 at The Soraya on Sept. 30, 2023. | Photo: Carla Lopez, Luque Photography.

Then, after a bit of a wait, and without fanfare, the curtain slowly rose to a low lit, nearly empty stage save for a grand piano prominently placed up right. And, in concert fashion, pianist Vicki Ray walked out, bowed and settled at the piano. It was an appropriate start to the evening, Ted Shawn’s SERENATA MORISCA, a true origin piece for Modern afficionados and novices alike, originally choreographed in 1916. Shawn and Ruth St. Denis were both dedicated pioneers of Modern dance and it was their training that inspired Graham, Doris Humphrey, Charles Weidman, Jack Cole and so many others. Shawn, seeing 22 year old Graham’s talent, personally created the work for her which she performed with the Denishawn touring company.

Ray then began to play the remote and nearly lost music of Mario Tarenghi prompting the entrance of the spirited Marzia Mimoli who summoned the time and life force of Graham. Mimoli appeared in a costume designed by Graham herself, after Pearl Wheeler, a costumer and dancer with Denishawn. A black midriff choli, with an over-circular skirt resting on her hips was of warm oranges, yellows and golds beautifully accentuating the stylized movement borrowed from Indian, Egyptian, and modern dance. She performed with great aplomb, stylizing hints of its origin with her sudden stops, angular poses and bursts of movement. Her lovely technical ease made this 4-minute piece a fascinating look back in time.

We then moved to Dark Meadow Suite, which premiered in January 1946. It is an abstract work influenced by Graham’s search for connection and meaning in, among many things, Karl Jung’s archetypical analysis and Francis M. Kornford’s reinterpretation of the Origin of Western Thought. In this piece Graham wanted to represent the eternal adventure of seeking. In the 1946 piece the leads were identified as, “She who seeks” (Martha Graham), “He who Summons” (Erick Hawkins), and She of the Ground” (May O’Donnell) with nine dancers named “They who dance together.” It was a true tribute to Graham’s unique invention in the modern movement.

In keeping with Graham’s distinctive work, the company presented difficult off centered partnering, testing the strength of both male and females, with difficult counter balances on the floor, and while standing, then adding overhead positions only seen in Egyptian friezes. The remarkable technically controlled Graham female dancers, Ane Arrieta, Meagan King, Devin Loh, and Marzia Memoli were mesmerizing with their fluency and intelligence of form. Their male partners Lloyd Knight, James Anthony, Alessio

Crognale-Roberts and Richard Villaverde lifted and sustained, with powerful canniness, the more- than-difficult support of their charges. Graham’s use of space and design showed the discernment of her work.

Stuart Hodes, dancer with the Graham Company, a choreographer, educator and author spoke candidly about performing Dark Meadow. He admits “not many can tell you what it’s about.” Others have said “it’s about sex.” “Yes,” he says, but she gives it such a personification… then he admitted “This piece, is considered one of Martha’s greatest.”

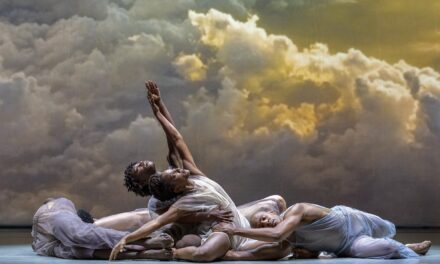

Martha Graham Dance Company in the world premiere of a reorchestrated version of Agnes de Mille’s “Rodeo” performed at The Soraya on Sept. 30, 2023.| Photo: Carla Lopez, Luque Photography.

After an extended intermission, the audience was back to see the anticipated Agnes DeMille’s RODEO or The Courting at Burnt Ranch. This is a fully American creation, very contemporary at the time, and still communicates such basic human needs and emotions often with good humor and honesty. De Mille, whose love for and skill in dance, in spite of her rough beginnings and rejections as a dancer and a woman in a male dominated business, became a sage choreographer who understood her characters sense of strengths, loneliness, rejections, courage and isolation. It was DeMille’s intention, to move from classic ballet to develop “new forms, new styles, new experiments.” And with the Ballet Russes de Monte Carlo in 1942 she did just that. She found her full and enduring success with Rodeo, not only as a choreographer but as a dancer, and quickly moved on to become a world-renowned and sought after artist.

After her version of the Cowgirl earned her 22 curtain calls, casting became difficult. The subtlety of the role as she explains has its distinctions, “She (the Cowgirl) acts like a boy, not to be a boy, but to be liked by the boys.” Laurel Dalley Smith’s, charming, wild colt-like interpretation, very well studied, researched and coached, does her proud. Her acting was engaging, her self-consciousness charming, her comedic sense of timing grabbed attention. This young filly trying to find a place in a world she did not quite understand yet. She became a sympathetic character who engaged and charmed. She did a terrific job and was a spirited natural in this role.

Martha Graham Dance Company in the world premiere of a reorchestrated version of Agnes de Mille’s “Rodeo” performed at The Soraya on Sept. 30, 2023.| Photo: Carla Lopez, Luque Photography.

However, what is missing is the powerful male presence riding that vast range. The American Vernacular, the power of the fully male world, with the use of females as décor on their arm which says much of this time. DeMille wanted the emotions of the man riding, “his joy, his power, his domination, his pride and strength…How did our cowboy stand and walk?” She questions. “He slouches, he squints in the hard sun, it’s hot where he is, he takes his time, never hurries” but when he rides, his body jerks as it might be with roper and rider. Disappointingly The life of the hard driving, hard drinking, hard living everyman in this revival never lives up to expectations; so, right down the line, the love interests were absent, neutral and ineffective.

What could have been of help was costuming, however Designer Oana Botez, in an effort to update and make this piece inclusive either missed the entire point of the ballet or ignored it. The costumer traded dirty jeans, plaid shirts, a sweat scarf, cowboy hat and dusty boots for pink and pastel colored pants and matching shirts with brocade dripping down their thighs which only competed with the females…. So not much “cowboy” going on. Unfortunately, white tap boots did not make a tapper. The Champion Roper (Richard Villaverde) and Head Wrangler (Alessio Crognale-Roberts) were hardly distinguishable from each other. The set originally designed by Oliver Smith, was done by Beowulf Boritt for MGDC and was sufficiently sparce showing the vast plains with pushed perspective of livestock fences much like the original.

Composer, Aaron Copland’s, vast Americana masterpiece was hard to beat by the Gabriel Witcher and Company’s group with Gabriel Witcher-on Fiddle leading his Blue Grass Band, Bryan Sutton’s Guitar, Paul Viapiano’s Mandolin, Wes Corbett’s Banjo, Isaiah Gage’s Cello, and Paul Kowert’s Bass; along with the Conductor, Christopher Rountree’s Wild Up, with Vicki Ray on Piano, Adrianne Pope-Violin, Adam Milstein– Violin, Derek Stein-Cello, Andrew Tholl-Violin, Linnea Powell-Viola, Mia Barcia-Colombo-Cello, Mona Tian-Violin, and Diana Wade-Viola. The adaptations and re-working of Copeland’s distinctive score was simply a shadow of the original, which the addition of Blue Grass never fully realized.

All-in-all, a 50-year connection to this piece and its principals makes judgement clear. A number of elements need to be re-examined in respect to the historic context and the spirit of DeMille’s wonderful and classic gift of Americana.

Xin Ying and Lloyd Knight in Martha Graham’s “Maple Leaf Rag,”performed in the world premiere of GRAHAM100 at The Soraya on Sept. 30, 2023. | Photo: Carla Lopez, Luque Photography.

The last piece of the evening was Graham’s Scott Joplin’s, Maple Leaf Rag premiered October 2, 1990, at New York’s City Center. Vicki Ray, once again at the grand piano, shared the stage with a type of bouncing balance beam with wooden supports that rocked with every breath and movement. On the darkened stage, the piece began with a foreboding pulsating single note. Dancer, Lloyd Knight supporting the petite Xin Ying high above his head in a frieze-like pose, heroically crossed downstage as though God and Goddess were just passing through. And with short warning, the recorded voice of Martha Graham quickly changed the mood, and the frolic began.

Miss Martha, already in her 90’s was dubbed “Mirthless Martha” by her musical director and composer Louis Horst. It was said, she turned to him when stumped by the pressure of creating yet another new work, of which there were 181 known pieces, and said, “Oh, Louis, play me the Maple Leaf Rag!” He did just that, and it became the musical inspiration for this work. It freed Martha to create sudden playfulness juxtaposed with her known and beloved heroic works. It is a tongue-in-cheek send-up of “Graham making fun of Graham.” It freed her and was a most delightful and wacky roguishness for the dancers. The toggling back and forth of the iconic and recognizable signature moves against the balance-beamed antics, brought titters from the audience “in the know.” All delighted in watching and guessing the origins of this merry-making. She borrowed from Clytemnestra, Appalachian Spring, Lamentations, and more, with a running gag of a female dancer using her over-circular modern white silk skirt to swirl across the stage with traveling turns where the rule of 3 (only do something three times to get a laugh) might have been a welcome edit.

The circus-like balancing and gymnastics headed by Knight, Ying and Anne Souder led the romp with the company dancers: So Young An, James Anthony, Ane Arrieta, Alessio Crognale-Roberts, Laurel Dalley Smith, Zachary Jeppsen, Meagan King, Antonio Leone, Devin Loh, Marzia Memoli, Matthew Spangler, Richard Villaverde, Leslie Andrea Williams, and Travon Williams. They all jumped in, fearlessly balancing, leaping, hopping, cartwheeling, counter balancing, all with effortless abandon.

Maple Leaf Rag is a lovely gift for both experts and novices alike to end this evening of historical work. In the end, the audience was compelled to stand and acknowledge the important contribution of the steady and brilliant leadership of Artistic Director, Janet Eilber, along with the dancers and alumni. Thor Steingraber more than acknowledged the generosity of the Saroya Family and the benefactors that are honoring this 100 years of genius work by Martha Graham.

To learn more about the Martha Graham Dance Company, please visit their website.

For more information about The Soraya Theatre, please visit their website.

Written by Joanne DiVito for LA Dance Chronicle.

Featured image: Lloyd Knight and Anne Souder in Martha Graham’s “Dark Meadow Suite,” performed in the world premiere of GRAHAM100 at The Soraya on Sept. 30, 2023. | Photo: Carla Lopez, Luque Photography.