The Getty Research Institute’s “Dancers on Film” series is currently a virtual forum for screening and discussion. On Thursday, in his introduction, deputy director Andrew Perchuk explained that the institute previously had trouble connecting its collection of archival dance footage, until it met its match in research specialist Kristin Juarez, who would lead this series.

“This series looks at formal experiments between the moving image, and the moving body, and it asks us to consider how we can archive dance, and what dance can archive,” Juarez shared.

In conjunction with the African American Art History initiative (and the first exhibit that will come out of that initiative) Juarez led a screening and discussion with director Madeleine Hunt-Ehrlich, accompanied by a pre-screening of classic movie musical Swing Time (1936).

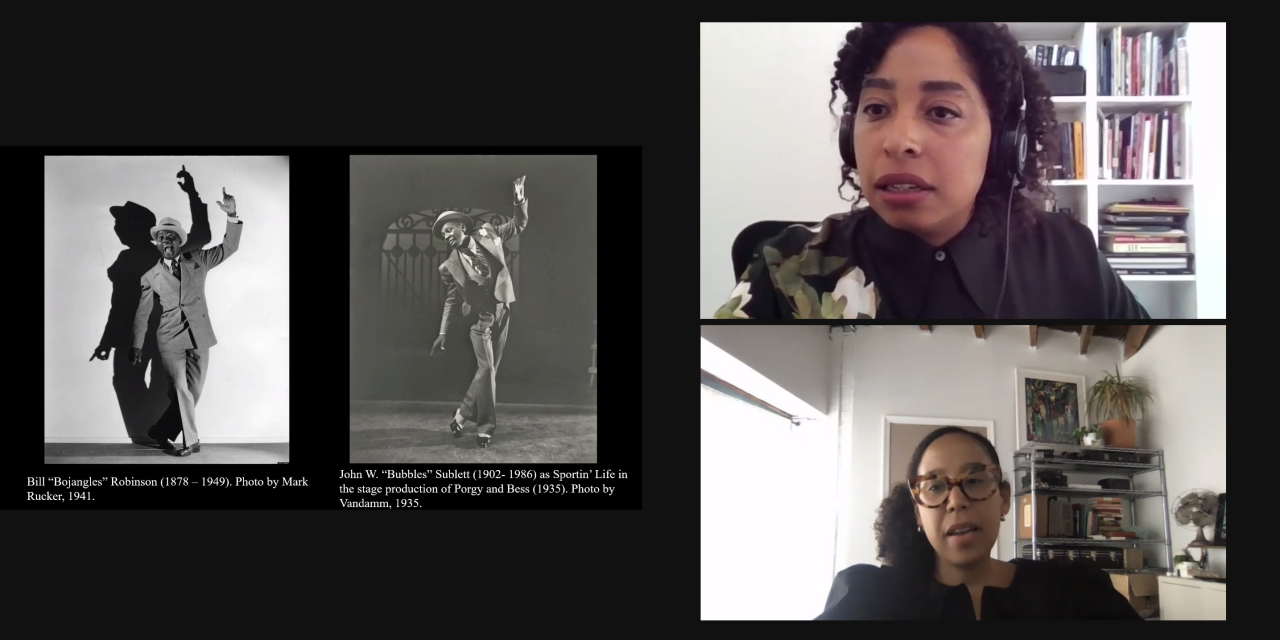

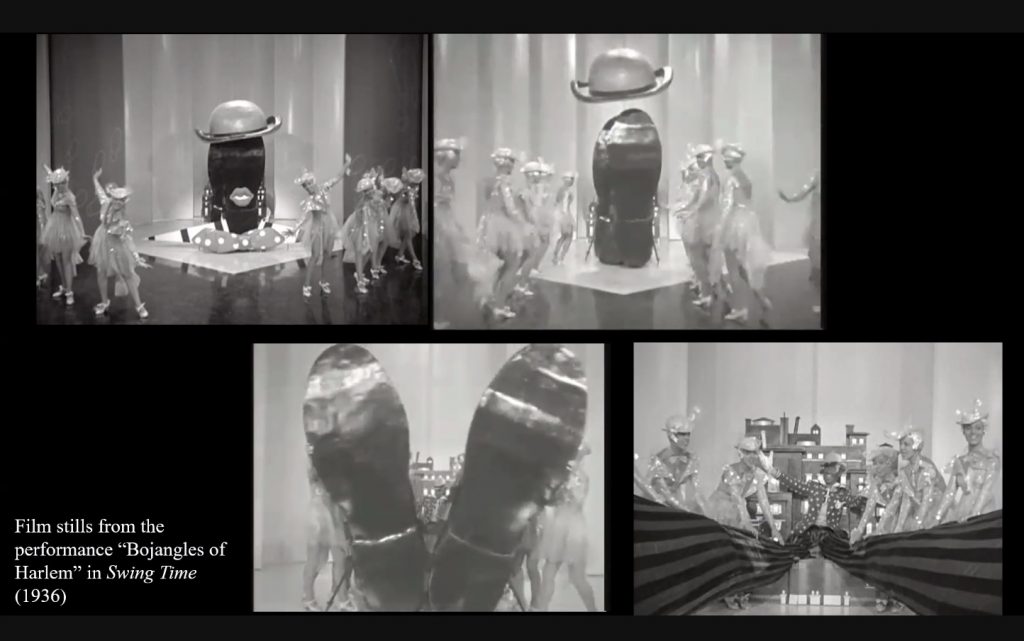

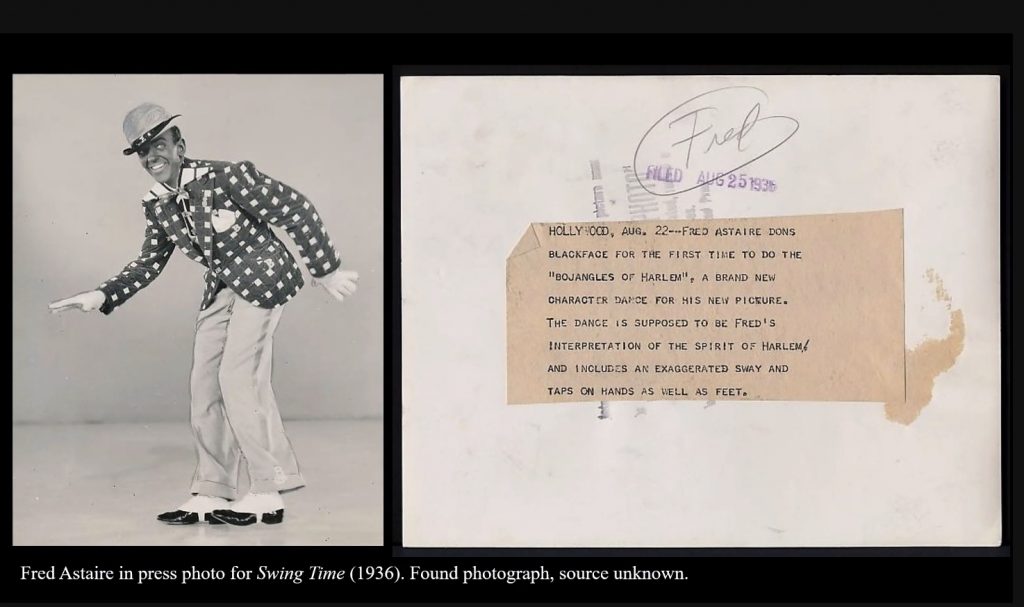

Swing Time is a musical staple, starring Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers in perhaps what is one of the most iconic dance scenes of the era. But as Juarez and Hunt-Ehrlich discussed, what could be a near-perfect musical is compromised by a bizarre theatrical number, “Bojangles of Harlem,” in which Astaire appears in blackface.

Juarez and Hunt-Ehrlich also discussed the famous lindy hop scene from Hellzapoppin (1941), in which Frankie Manning, Norma Miller, Billy Ricker dance an astonishingly fast and virtuosic number, all dressed as the theater’s maintenance crew. The set is clearly marked with indications that this is happening backstage – an assertion by the white filmmakers, as Hunt-Ehrlich put it, that this is what Black people do when we’re not around. And this scene is not an isolated incident: the genre saw a lot of Black performance that took place offstage, without the formal audience gaze and the splendor of the full-orchestra club setting.

In the context of these two scenes, Hunt-Ehrlich explained that these tropes, these displays of pageantry in many ways inform her film work. Juarez nodded, noting Brenda Dixon Gottschild’s work Waltzing in the Dark on race and vaudeville in the swing era, which discusses blackface as a mask and disguise for deception and protection.

“Pageantry is extremely black,” Hunt-Ehrlich said, framing “pageantry as protection, for survival, for Black people who have learned to perform in white space.”

Hunt-Ehrlich cites a long love affair with film, cinema, and old movies. She began her career in still photography, working for Simone Leigh and Jeanne Moutoussamy-Ashe before going to film school in search of a less static means of capture. She describes filmmaking as a medium that can be manipulated like sculpture or painting: deeply structural in that it uses a set of languages. In her work, she aims to change the viewer experience by reframing pieces of the language.

“I know that the body is going to feel this way…it’s almost like you’re creating a spatial experience, or I think of it that way, as very physical. I think of it as a set of languages that we can kind of…understand what the outcome of the syllables will be,” she explained. “What I think is interesting is pulling out some of those syllables, and then using something that no one expects. What does that do to the body of the audience, experiencing that piece?”

They then screened two of Hunt-Ehrlich’s films, Footnote to the West and Spit on the Broom. Both are beautifully disruptive, flipping tropes of the musical era on their heads, perhaps in reclamation of the screen space for Black women – but to reduce the work to just reclamation would be inaccurate. The films are short but saturated with style and nuance; I’d have to view several more times just to begin unpacking. That’s part of their loveliness – there is so much to recognize and wrestle with, and the viewer begins to sort of reorient their understanding of the musical archetypes in order to fit this new narrative, rearranging the syllables.

After screening, Juarez and Hunt-Ehrlich discussed the United Order of Tents, a very secretive society of Black women that began around the time of the Underground Railroad and helped many to freedom. Though their secrecy began out of necessity, it has continued to be a hallmark of the society, except through “manless weddings” that they would stage publicly as a club. The Tents would essentially create the pageantry of a wedding and fill the male roles with women. Hunt-Ehrlich found records of these weddings in the archive and found that they facilitated even more understanding of pageantry for her.

“It just really unlocked for me, you know, the use of pageantry in these public-facing fundraisers… the event you could go to… was so different than the work they were doing secretly in their communities, primarily in the South, that could’ve gotten them in trouble at times,” she said.

In Spit on the Broom, two women dressed as bride and groom dance together in an explicitly Astaire-and-Rogers style, through a picturesque garden. There’s also portraiture and even mirrors that signify this forward-facing experience, almost theatrical behavior, while the Tents facilitate disruption behind the scenes.

Jaurez explains that Hunt- Ehrlich works to “blur distinctions between folklore and documentary in her films, creating a world that is both grounded in reality and surreal, unbound by the rules of invisible cinema and singular notions of truth.”

I think, for the purposes of this screening and discussion, that she managed to make me question whether the distinctions between folklore and documentary truly exist – and to answer Juarez’s first prompt, try as we might to archive dance, I think it’s a bit more accurate to say that dance is archiving us.

To visit The Getty Research Institute, click HERE.

Written by Celine Kiner for LA Dance Chronicle.

Featured image: Madeleine Hunt-Edrlich and Kristin Juarez – Screenshot collage by LADC