In 1983 I was a graduate student in the UCLA Dance Department majoring in choreography. One day I followed a couple of my comrades up to the film school where I crewed for an Experimental Video class taught by this amazing woman, Shirley Clarke. I made my first video during the class lunch hour but I don’t think Shirley ever saw it, because she left that year. I had, however, learned to use cameras, so I shot a lot of dance and strolled into an Advanced Editing class where they welcomed me with open arms.

After two quarters of taking only film classes, I felt like I was walking a fine line between the film school and the dance department when Allegra Fuller Snyder returned from sabbatical. Someone told me I should meet with her, so I did. She gave me a copy of the proposal she had written for the NEA to create funding for Dance Film and Video and gave me an assignment to write down the differences and similarities between film/video and dance. Shortly after this I decided to do a thesis on using video as a choreographic tool. I finished my MA in Dance, and formally entered the film school that Fall.

Since I had taken most of the video classes offered, I thought I’d go upstairs and check out the animation workshop. There I met Dan McLaughlin who appeared thrilled to have a dancer in his class. My first 16mm film was called “Tournants,” a history of concert dance in cutouts. It did pretty well, got into some festivals and there was even a write up in Dance Magazine by Deirdre Towers.

In 1986 I performed for the last time (although I didn’t know it) and went to Boston, my home, to do an internship at WGBH‘s New Television Workshop with producer Susan Dowling. At the time she was editing some shows for Alive Off Center, including work by Michael Clarke, Bill T. Jones and Arnie Zane, Carol Armitage, and Trisha Brown. I became her assistant editor for a summer and had the time of my life.

Returning to UCLA I completed my thesis film, “For Dancers.” With about 50 cents in my pocket I again returned to Boston and took a job as the assistant video curator at the Institute of Contemporary Art, followed by a year as the assistant film curator at the Harvard Film Archive. I’m mentioning these jobs because they gave me important exposure to some amazing artists like Bill Viola and Raul Ruiz who very much employ dance and movement in their work, and I also became aware of the nuts and bolts of programming, installation and distribution. In 1991 I was more than astonished when the University of Texas at Austin offered me a job as an assistant professor in their Radio, Television and Film Department. Twenty nine years later, I am a recent retiree from teaching TV/Film production at California State University Los Angeles, so I can devote more time to complete the feature documentary, “Bella, Citizen Artist,” about the late Bella Lewitzky, choreographer, dancer and arts advocate from in Los Angeles.

Lately, I have seen an explosion of dance media projects, primarily due to current restrictions on live performance brought on by the Covid-19 pandemic. It’s been thrilling to see how choreographers are working with filmmakers and the camera. In this essay I’d like to address what choreographers need to learn to better communicate with media makers and become informed media makers themselves.

In making Dance For The Camera the operative word for me is “Camera.” It’s not dance anymore. Choreographers‘ eyes need to be retrained to see and understand the frame, the place where dance and media meet. This can be done through viewing seminal works, reading about aesthetics and theory, and actively engaging with the production process where concepts can be put into practice. Choreographers must have cameras in their hands. They must understand focus, exposure, camera movement, composition, and shot sequence/design. They need to be able to choose a media format as they would choose a palette to paint from. They need to know how to make informed decisions about their work and understand the meaning of the images they are creating. Filmmaking is a lot like dancing, you have to do it; you can’t fake it.

One big step is to separate documentation and Dance For The Camera. Everyone needs to have his or her pieces recorded, but documentation reinforces the perception that seeing the dance is the goal. Look at the best examples of the genre. Some traditional Hollywood musicals contain elements that might be considered dance for the camera, but this art form really developed from experimental film and video. Dance For The Camera has a rich history.

Here are some seminal works I think every choreographer should see:

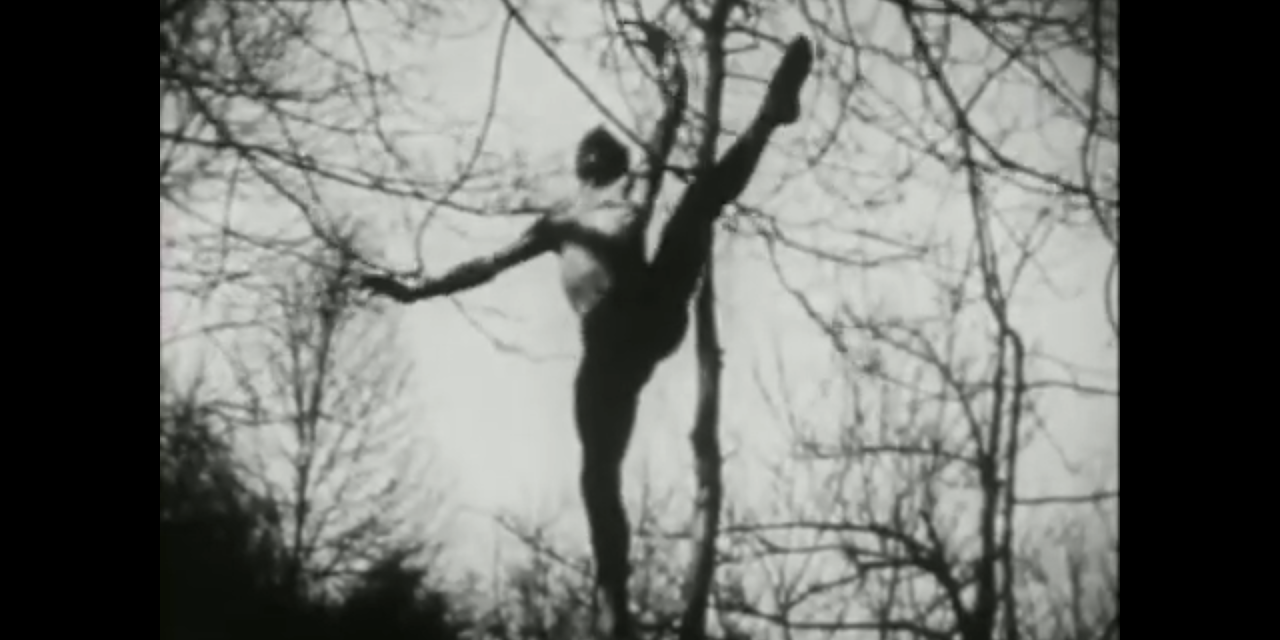

A Study in Choreography For Camera

Director: Maya Deren 1945

Dancer: Talley Beatty

Maya Deren has been recognized as one of the first American, experimental filmmakers. It is no coincidence that she was also a dancer, working and studying with Katherine Dunham. This film traverses film time and space through Talley Beatty’s movement. There is no sound. Shot in black and white, reversal, film stock, this work may seem dated to you, but look closely at each cut and observe what can be done on film to create a new way of looking at movement and dance. Ms. Deren went on to create additional works including Meshes of the Afternoon, At Land, Ritual in Transfigured Time and Meditation on Violence.

Nine Variations On A Theme

Director: Hilary Harris, 1967

Dancer: Bettie de Jong

Music: McNeil Robinson, Bonnie Lichter

This film is like the bible for how to shoot dance. In this film the incredible Bettie de Jong performs the same phrase 9 times while Hilary Harris shoots and edits it in 9 different ways. From long shot/mis en scene to montage, still camera to moving camera – it’s all here.

Dance In The Sun

Director: Shirley Clarke, 1953

Dancer: Daniel Nagrin

Experimental and documentary filmmaker, Shirley Clarke continued in the tradition of Maya Deren with her first film Dance In The Sun. Featuring Daniel Nagrin, a dance begun in a studio crosses through time and space to a beach and dunes. Ms. Clarke also had a dance background, studying with Martha Graham, Doris Humphrey and Hanya Holm, before turning her energies into filmmaking. She was a member of Filmmakers In America along with Maya Deren, Stan Brakhage, and Jonas Mekas. Her films, The Connection and Portrait of Jason, were groundbreaking, not only in their filmic technique, but also in her approach to often neglected subject matter.

Iowa Blizzard

Director: Elaine Summers, 1973

Elaine Summers was one of the founding members of the Judson Dance Theatre. “Film is very much a dance medium,” she told The New York Times in 1977, adding that it “presents many facets of dance: slow motion, fantasy of configuration, manipulation of space, distortion of time.” She made this film at Iowa University where she was an artist in residence. Arriving in the middle of a blizzard she involved 3 camera people and 12 dancers. In editing she overlayed the film four times.

Pas de deux

Director: Norman McLaren, 1968

Dancers: Margaret Mercier, Vincent Warren

Supported by the National Film Board of Canada, this film is a study in the use of high-contrast film and optical printing. This was an incredibly tedious process, but the results produced a work that is highly sensual and timeless. Norman McLaren went on to make many important films, including Neighbors and Rhtymetic.

Written by Bridget Murnane for LA Dance Chronicle.

Featured image: Screen Capture From Maya DEREN, A Study In Choreography For Camera (1945)