Kicking off part deux of my LA Nutcracker Series is a review of Los Angeles Ballet’s take on the Tchaikovsky Christmas special. Now taking on its 13th season, the company’s annual show has become a holiday staple, which they perform at different venues throughout the city every weekend between Thanksgiving and Christmas. The December 2 production I attended took place at the Alex Theatre in Glendale and drew crowds of families with children dressed in their holiday best, ready to be amazed and entertained. They were surely not disappointed, given that LAB’s special twists were able to brighten some of the historically duller parts of the ballet, ensuring that the program’s theatrical aspect remain equally impo

For starters, the story’s setting has been updated to Los Angeles, 1912. Main character Clara Silberhaus’ last name has also been changed to Staulbaum, which translates to “mature tree”, an appropriate nod to her character’s growth later in the ballet.

In the very first scene we see Clara (Mackenzie Moser), her brother Fritz (Zachary Li) and a group of their friends playing/fighting over her prized doll Marie (an essential part of the story later on), when they suddenly become aware of the noise rising from behind the scrim (painted to look like a hallway) separating them from the rest of the party. They gather to peek through the “crack” between the double doors and as Tchaikovsky’s overture increases in intensity, the “wall” suddenly becomes transparent, revealing the Christmas Eve preparations on the other side, and the ballet’s first clever touch of enchantment. Moments later, the screen is lifted, and the children and audience are invited to join the party, headed by Clara’s parents (Joshua Brown and Chelsea Paige Johnston).

Los Angeles Ballet’s Nutcracker – Petra Conti, Tigran Sargsyan and LAB Ensemble in The Nutcracker; Photo: Reed Hutchinson

After a few toasts and some merriment, in comes showstopper and dancer extraordinaire: Uncle Drosselmeyer (Zheng Hua Li). Traditionally a more mysterious character, Li brings a new perspective to his performance, combining Drosselmeyer’s original allure with characteristics akin to the more modern concept of a “goofy uncle”, in order to emphasize his status as an eccentric clock and toy maker who helps set the rest of the ballet’s events in motion. His flirty greetings and overly joyous gestures give him the appearance of a sort-of Santa Claus as he rains gifts upon the kids. The party especially comes to life with his introduction of a few life-sized dolls whose short routines demonstrate the company’s finesse and ability among a few of their principal dancers. An entourage of some of LAB’s best, they include Jeongkon Kim and Laura Chachich as the coupled Harlequin and Columbine dolls, Akimitsu Yahata as the Russian Cossack and of course, Joshua Schwartz as the show’s namesake Nutcracker doll. Kim and Chachich form the greatest dancing duo of the night, with tight movements that are at once mechanical and airy. Less obvious as a doll, but equally effective as a dancer, Yahata is strong, yet manages to stay light on his feet through every vertical jump. Schwartz’s shiny suit and gentlemanly salutes are appealing to Clara who obsesses over him. A cute scene with Drosselmeyer actually bending him at the waste and using his jaw to crack a nut open is an adorable touch. Clara’s fondness for him potentially grows further after he smacks the adorably disobedient Fritz who pulls at his shiny red suit and messes with him to the point of temporarily breaking him, before Uncle Drosselmeyer steps in, makes a few unclear adjustments and saves the toy from being thrown away. The Nutcracker’s whispering in Clara’s ear when no one else is looking forms a stronger bond between the two and adds to the charming details LAB has become famous for including in their retelling of the ballet’s plot.

Los Angeles Ballet’s Nutcracker – Jasmine Perry and Joshua Brown in The Nutcracker; Photo: Reed Hutchinson

A well-choreographed group number during which all the children are sent out of the room, except Clara. Already distinguishing herself as the only child wearing pointe shoes, Moser matches the adults’ elegance with her delicate movements in a dance reminiscent of historical turn-of-the-20th-century routines combined with slight touches of ballet. Though brief, the company uses the space on stage well, adding an extra dimension to what is classically known as the more-boring half of the ballet, before Clara ventures into the awaiting magical kingdoms after midnight.

Once the party is over, she is put to bed with doll Marie, and the nutcracker is sat vigilantly by her headboard, setting up the next scene containing an exciting visit from a sneaky army of mice. In an oddly comedic moment, Drosselmeyer pops into a grandfather clock gifted earlier to Clara’s parents, literally becoming the face of the clock and rocking his head from side-to-side with smiles and expressions silly enough to make the harlequin doll jealous. The final bell tolls and pitter-pattering mice appear, surrounding the sound asleep Clara in bed before briefly disappearing. Played by a myriad of adult dancers in soft, charcoal-colored costumes with tall heads, their ghoulish appearance is softened with a routine mostly consisting of a few spinning kicks and a conga line. The addition of a very cute Baby Mouse (Rosalie Winters) who follows the big kids around the living room is a plus. Clara awakes just in time to see the Staulbaum’s tree growing taller and dwarfing the chaotic scene of suddenly appearing dancing dolls below. Drosselmeyer appears leading an army of toy soldiers to defend his niece from the horde of mice. Consisting mostly of the children from the party, along with a few others, the soldiers’ general is Clara’s nutcracker come to life. As he begins marching and instructing his regiment to attack, out leaps the Mouse King (Magnus Christoffersen), complete with cloak and crown.

The battle is short and well-coordinated, with sudden exciting advances and comic Looney Toons–esque scenes of medics carrying out wounded mice. The King inevitably falls at the Nutcracker’s hand and his defeated army retreats. Clara’s hero transforms into a prince through a slightly underwhelming reveal that involves him turning his back to the audience, then turning back around without his doll-like mask. Schwartz’s warm smile adds life to the character. After he gives our heroine a new pair of ballet shoes as a thank you gift for breaking his spell, the two perform a charming duet. As the music settles, the bubbly Drosselmeyer appears yet again to whisk the couple away on a sleigh and take them on more adventures together.

The Land of Snow scene showcases a winter wonderland of frosted treetops in the background and an entourage of snowflakes ready to greet the duo with a pretty routine consisting of light scampering and soft arabesques that matches their namesake’s natural movement. Rather than showcasing a Snow Queen and Cavalier, choreographer and Artistic Directors Thordal Christensen and Colleen Neary, and Executive Director Julie Whittaker have chosen to forego the inclusion of their pas de deux and concentrate the drama on the much-anticipated Grand Pas de Deux later in the program. Instead, the focus is purely on the snowflakes. As it starts to snow, a choir joins the soundtrack, adding an angelic sheen to the dancers bourrées in their sparkling costumes and icy crowns. The flair of flutes triggers synchronized jumps and spins, which the company members perform in duets, trios and quartets. As their section ends, Drosselmeyer appears again to push Clara and the Nutcracker Prince’s sleigh into the next realm, ending Act I.

After an intermission, Act II opens with a new setting: the moonlit Palace by the Sea (an alternative to The Land of Sweets) where all of Clara’s dolls are coming to life. Rather than feature a decadent dance of desserts, Los Angeles Ballet has chosen to update the story by mostly foregoing the old 1800s associations between certain countries and the foods and drinks paraded in the original ballet.

One aspect that takes away from their modern setup, however, is the inclusion of two goofy attendants preparing the palace for their arrival in Ottoman-style clothing. Intended to be jesters, the characters are weird, their costumes out-of-place and their antics unfunny—an odd choice to play the comic relief in The Nutcracker’s most important scene.

That blip aside, Tchaikovsky’s suite is executed very well. One of the most noticeable differences is the replacement of the Sugar Plum Fairy with Clara’s doll Marie (Petra Conti). More of a name change than anything else, the switch may seem blasphemous at first for diehard Nutcracker fans because of the character’s significance to the original material. However, it adds a much-appreciated layer of depth to the plot, allowing the ballet to move beyond a child’s sugar-induced fever dream and adding instead a glimpse at Clara’s hopes and dreams for the future as she idealizes Marie. This is especially evident as she watches her leap straight into the dance of the Sugar Plum Fairy shortly after her arrival and the Nutcracker Prince’s explanation of the earlier war waged between his army and the mice. Marie’s solo would usually be featured toward the end of the act, but placing it here emphasizes her importance to Clara as a role model. The infantile music never really loses its charm no matter how many times I see the ballet. Of course, the biggest factor in this is always the ballerina. Conti’s nimbleness and supple movements as she tip-toes across the stage and floats her arms upward and downward through the air are a thing to be admired.

The Spanish Dancers (or “Chocolate” for those still dreaming of the Land of Sweets) are the first of the dolls to perform. They consist of a quartet made up of two couples (Christoffersen, Helena Thordal-Christensen, Shelby Whallon and Dallas Finley) dressed in earth tones: red, orange and yellow. Quick turns and skirt flares in a balletic routine sporting a hint of Paso Doble make up the bulk of their performance. Unfortunately, their portion is the weakest of the bunch. There are quite a few moments wherein the couples are out of sync.

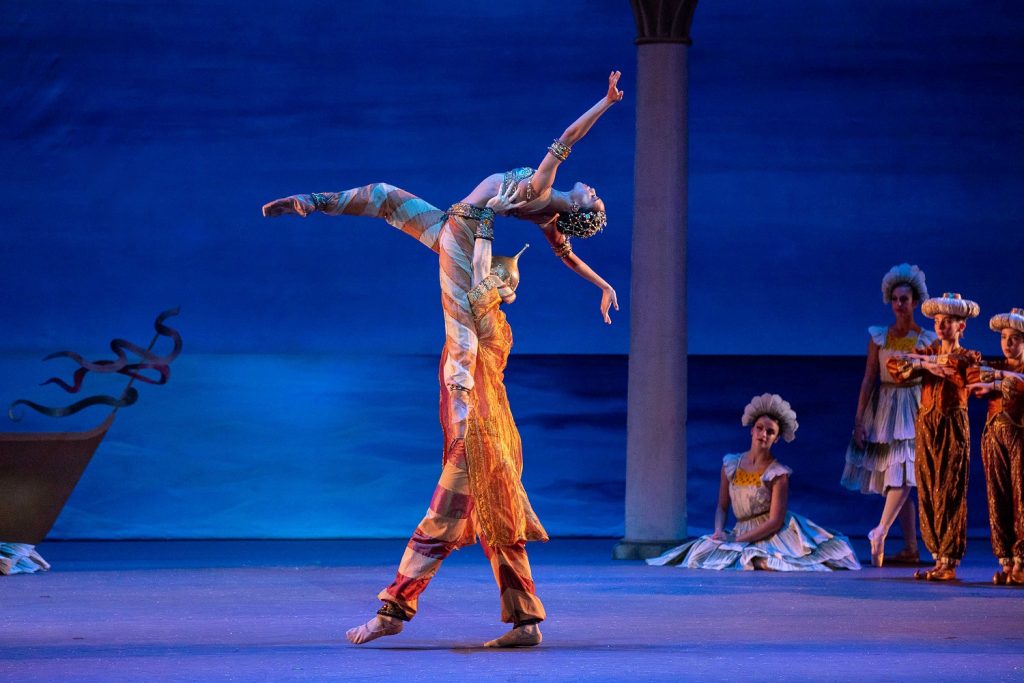

Next up is Arabia (formerly “Coffee”), which maintains its reputation as being the sexiest number of the bunch. The couple (Bianca Bulle and Eris Nezha) perform their piece marvelously. Bulle is the standout amongst the two with her glittering outfit and extreme poise, which she maintains though every extreme lift. Their entrance features Nezha carrying Bulle out from behind the curtains as she arches her back over his arm. Her long extensions, slow, music box turns and upside-down holds are smooth and seductive. Their lingering eye contact creates a sensual story. Although this section is almost too inappropriate to be featured in such a kid-friendly ballet, it’s difficult to imagine the suite without it—Tchaikovsky’s music, with its clicking tambourine jingles, and their sultry and electric dancing. Somehow, the passionate undertones fall in line with LAB’s portrayal of Clara as a maturing young woman. At least in this rendition, the Arabian dance hinted at something deeper developing within her.

Another brilliant move by the company was to swap the tasteless Chinese “Tea” dance for a completely different performance which comes from the best and most congruent couple in the room: the Harlequin and Columbine dolls, presumably representing Italy. The music of course remains the same, charming as ever, but their bouncing routine is a welcome shift away from the cringe-y nodding and upward finger pointing featured in other ballets. Kim and Chachich’s moves are fresh, springy and full of dainty gestures that align with their characters. This includes Kim posing with bent elbows and outwardly flicked wrists, cocking his head to the side when staring at his partner and Chachich matching his quirk with her own version of squared wrists that manage not to take away from her overall limber appearance. It ends with her leaping in his arms effortlessly before pecking him on the cheek.

In the next scene, the Russian dancers (or “Candy Canes”) scene amp up the excitement by charging out from stage right as soon as Tchaikovsky’s well-loved soundtrack begins to play. The flashiest dance of the night, the high-energy, jump-kicking, boot-slapping number is a crowd favorite. Led by Yahata who appears earlier as one of Uncle Drosselmeyer’s new Christmas Eve gifts, the trio, which includes Costache Mihai and Clay Murray do not disappoint, drawing in the audience immediately with their high knee steps and triggering a clap-along that ends with thundering applause.

Much to my surprise LAB skips the “Marzipan” dance which includes one of the ballet’s most recognizable tunes: “The Reed Flutes”. Usually consisting of Danish shepherdesses and French mirliton players, the dance is often a cutesy hop-along en pointe. Though its absence helps cut down the ballet’s long, two-hour production by a few minutes, I missed hearing the music and can only wonder how LAB would have made it their own if they had to include it in their show.

Los Angeles’ Nutcracker – Petra Conti, Tigran Sargsyan and LAB Ensemble in The Nutcracker; Photo: Reed Hutchinson

Up next is a slight departure from the dolls but falls back in with the ballet’s traditional line up: Mother Ginger and her Hansels and Gretels (often called “Polichinelles”) are classic figures which LAB has in no way reinvented or changed, presumably due to the segment’s cute incorporation of more kiddos. (There are often more children featured in other company productions of The Nutcracker). Their number is adorable and keeps viewers “oohing and aahing” throughout. Mother Ginger’s costume is an actual gingerbread house, seemingly decked out with all the candy missing in the rest of Act II. Her children, a group of eight boys and girls, are some of the ones seen earlier in the ballet: during the Christmas Eve party, as the toy soldiers fighting the mice, and as attendants that introduce a few of the dolls before their dances (“Arabia” is an example). Waving as though a part of a Macy’s Day parade float, Ann Haskins acts as Mother Ginger and introduces the kids as they pop out in German overalls and dresses—a tie in to the rest of the scene’s international theme, given the fact that gingerbread houses are originally a German yuletide treat. A few flips and bows later, the kids are back inside their mother’s protective abode, and therein ends the United Nations of dance!

Ten ladies dressed as sunflowers take center stage next to perform the Waltz of the Flowers. Yellow petals act as crowns around their head and two-tiered green skirts bring a sunny contrast to the darkening sky in the palace’s background, which shows time advancing throughout the evening, thanks to Penny Jacobus’ lighting design and Tyler Lambert-Perkins’ lighting execution. The flowers have no Dew Drop Fairy leader. Rather than skim her part as they had that of the Snow Queen in The Land of Snow, Clara rises from her and the Nutcracker Prince’s shared throne on stage left to join the ensemble, filling in the role herself. The move shows off Clara’s gradual maturity throughout the course of the ballet and allows Moser to showcase her skill as a ballerina. She executes the role with agility and grace, the movements of her controlled développés mimicking the blooming of a flower. The sunflowers around her match her tenderness with waving arms. They allow her to shine as the prima without giving up their own spotlight completely. Together they create a very harmonious dance.

Last, but not least, is the Grand Pas de Deux between Marie and her nameless Prince (Tigran Sargsyan). Despite mostly residing in the background until now and engaging in very short two-step tidbits with Marie intermittently throughout the performances at the Palace by the Sea, Sargsyan can hold his weight as Conti’s companion. Their chemistry is palpable in this scene. Although the dance is lovely, with sweeping lifts and open-armed embraces that perfectly match the music’s highs and lows, some of the key moments take place between Clara and her Nutcracker Prince as they subtly smile and glance at one another throughout the dance. The twinkling looks Schwartz and Moser exchange as they watch a representation of adult versions of themselves dance together is quite magical. Their costumes are similar in color and style to that of Marie and her Prince and the overall vibe is that of two growing children accepting and anticipating a potential romantic future.

A grand finale takes place wherein each group comes out for one last flair and bow with the Nutcracker Prince joining in the parade of dolls. At the height of the excitement, Clara begins to look sleepy. She finally yawns and lies down under a spotlight that sets the rest of the production in darkness, giving the dolls enough time to scatter away. Her bed appears, and she is back in her room, asleep on her bedroom floor. Her parents walk in just in time to tuck her in and before the light fades, in the distance, the audience is given one last look at Clara’s mischievous Uncle Drosselmeyer and her beloved Nutcracker standing vigilant as always. They vanish, and she awakes with a startle, indicating the whole thing was a dream. As the ballet ends, you are left with a gnawing doubt that it may have all actually happened.

Los Angeles Ballet’s interpretation of Tchaikovsky’s classic may not be for those wanting a traditional Balanchine-style show, but their version is something more widely relatable to audiences today. They add a more solid plot to the storyline with beautiful choreography that still embraces the spirit of the ballet, keeping most of it intact, while shedding light on new, untold possibilities for the main characters. LAB’s Nutcracker ultimately adds a three-dimensional quality to Clara and her prince, which makes the production more enjoyable for people of all ages and perhaps the best local show in town.

Upcoming performances by the Los Angeles Ballet: Serenade & La Sylphide, March 2, Redondo Beach Performing Arts Center; March 9, CAP UCLA’s Royce Hall: and March 16 at the Alex Theatre.

For more information on the Los Angeles Ballet performances, click here.

Featured image: Bianca Bulle and Los Angeles Ballet Ensemble in Nutcracker; Photo: Reed Hutchinson