Braving the rain-filled drive from Riverside to Los Angeles, I turn into LA Dance Project’s parking lot off of Washington Boulevard. I park the car. As I enter their space, I am immediately greeted by two delightful women who welcome me and check me in. The space has an artsy, converted warehouse vibe—exposed wood ceilings and open space. Tea lights create a soothing ambience as jazzy hip hop plays softly in the background accompanying all the indistinguishable conversations happening throughout the foyer. A large bookcase lines one of the walls with books creatively stacked and arranged.

After some time, the house opens. The performance space is simple and elegant—the same exposed wood beam ceilings, exposed brick walls and a white accent wall. A third wall is half exposed brick and half graffiti-decorated windows. The audience sits on bare wood benches with black pillows. It reminds me of church pews.

The evening’s performance opens with Jamar Roberts’ “Lineage,” set to music by Tennessee composer, saxophonist, and flutist Zoh Amba and danced by Daisy Jacobson, Daphne Fernberger, Nayomi Van Brunt, Courtney Conovan, David Adrian Freeland Jr., Mario Gonzalez, Lorrin Brubaker, Vinicus Silva, Shu Kinouchi, Jeremy Coachman, Peter Mazurowski, and Oliver Greene-Cramer. The muted cool costumes are designed by Janie Taylor (and constructed by Christina Olson) and the lighting is designed by Caleb Wildman.

Roberts’ movement in “Lineage” is simple and elegant, like the performance space itself. However, it is brought alive with vivid punctuation—his movements sometimes striking like an exclamation point, entreating like a question mark, or pausing slightly only to continue on like a comma. His movement vocabulary consists of myriad combinations of angular limbs, successive and sweeping movements, undulating torsos, extended lines and curvatures of the spine. I am most drawn in by Roberts’ staging and the masterful ways he transitions between sections. His staging is dense and textured with different groupings doing different movements layered on top of one another. Yet, it is somehow orderly, perfectly framing the movement so nothing is lost. As I watch, I am able to see the distinctive parts and take in the whole at the same time. It is delightful to watch how he frames his movement and leads our eyes through it.

“Lineage” opens with the full ensemble dancing a stationary phrase in unison which proceeds to unfurl into a beautiful display of staging prowess. Right from the opening phrase, dancer Mario Gonzalez grabs my attention. The gorgeous articulation of his torso throughout the phrase work makes him a wonderful ambassador of Roberts’ language.

One section—centered around duet Lorrin Brubaker and Daphne Fernberger—is exquisite. Amba’s saxophone is the perfect companion to this tender duet, which is later joined by the ensemble. When the ensemble enters the space, Roberts employs them as a type of Greek chorus, except they observe instead of comment. Their intense and sustained gaze at times feels empathetic and other times borders on intrusive. Are they voyeurs? Onlookers? Witnesses? Supporters? That is never answered but their presence and gaze is poignant and intensifies the shared experience happening between Brubaker and Fernberger.

L.A. Dance Project – “Quartet for Five” by Bobbi Jene Smith and Or Schraiber – Photo by Aymeric Guilluy and Eyrau Chalalet

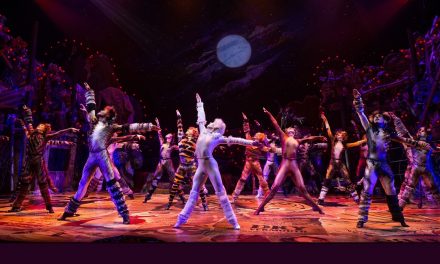

“Quartet for Five,” choreographed to Philip Glass by Bobbi Jene Smith and Or Schraiber, opens the second half of the evening. Wonderfully programmed, this piece is opposite Roberts’ in every way. “Quartet” features a white set with strong lighting designed by Clifton Taylor and adapted by Caleb Wildman. Three black chairs and a black table sit on stage left.. The dancers—Daisy Jacobson, Daphne Fernberger, Mario Gonzalez, Lorrin Brubaker, Jeremy Coachman—are dressed in black, white, and gray costumes designed by Victoria Bek.

I love the way Smith and Schraiber open this work. One at a time, dancers enter and exit the space, walking on strong diagonal lines until they reveal soloist Daphne Fernberger. She is a delight! Strong and exact in Smith and Schraiber’s specific and idiosyncratic movement, Fernberger’s face is a performance all its own. I am transfixed by the secrets she shares through her facial expressions and the movements of her head. Her performance of the movement is a lovely conversation with Glass’ strings.

“Quartet for Five” by Bobbi Jene Smith and Or Schraiber – Photo by Aymeric Guilluy and Eyrau Chalalet

In one section, Lorrin Brubaker and Jeremy Coachman dazzle in a fun duet that progresses from arguing to teasing to all-out frivolity in a footsy exchange reminiscent of Gene Kelly in “Singin’ In The Rain.”

Smith and Schraiber are clever in their subtle use of sexuality and attraction as a backdrop to play with the dynamics between certainty, explicitness, and subtext. The costumes and set design—the obvious and apparent—are black and white. Yet as you watch the way the dancers touch and interact, and the small passing expressions on their face, you are confronted with questions. And it’s wonderful because nothing is ever resolved or confirmed. It’s merely exposed, but only to the point that it makes you cock your head to the side as you wonder, “Did I just see what I think I saw?”

L.A. Dance Project – “Quartet for Five” by Bobbi Jene Smith and Or Schraiber – Photo by Aymeric Guilluy and Eyrau_Chalalet

One particularly revealing section happens in the center of the stage when—against Glass’ frenetic strings—the whole cast rushes into the middle of the stage in a bedlam of crazy polyamorous confusion. Everyone runs towards one another but they’re all unclear about who’s going to who, who wants who, or who will claim who. It was a striking image and crystallizing moment in the intention of the work.

L.A. Dance Project, led by Artistic Director Benjamin Millepied, presented a beautiful program filled with incredibly gracious artists who beautifully performed the work of three really interesting choreographers. The rainy drive from Riverside was totally worth it!

For more information on L.A. Dance Project, please visit their website.

This review was edited on 3/7/23 to correct an error.

Written by Marlita Hill for LA Dance Chronicle.

Featured image: L.A. Dance Project – “Quartet for Five” by Bobbi Jene Smith and Or Schraiber – Photo by Aymeric Guilluy and Eyrau Chalalet