There was much to admire at the intimate Charlie Chaplin Studios in Hollywood on the chilly evening of December 12, 2025. Jacob Jonas The Company, joined by the exquisite Sara Mearns of New York City Ballet, drew a devoted crowd of followers and curiosity seekers. The atmosphere was warm and welcoming—food scents in the air, manicured outdoor spaces glowing softly, and a prominently displayed table of Jonas’s memoir, Cemented Beauty, presented as a “meditation on the human experience.”

Jonas, whose artistic roots derive from hip hop, and whose collaborations span dance, film, music, and the written word, has built a notable presence in contemporary dance. With appearances at Jacob’s Pillow, The Wallis, and other respected venues, his ambition and drive are undeniable. His personal journey—most publicly his survival of stage-four non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma—has become central to both his artistic identity and public narrative.

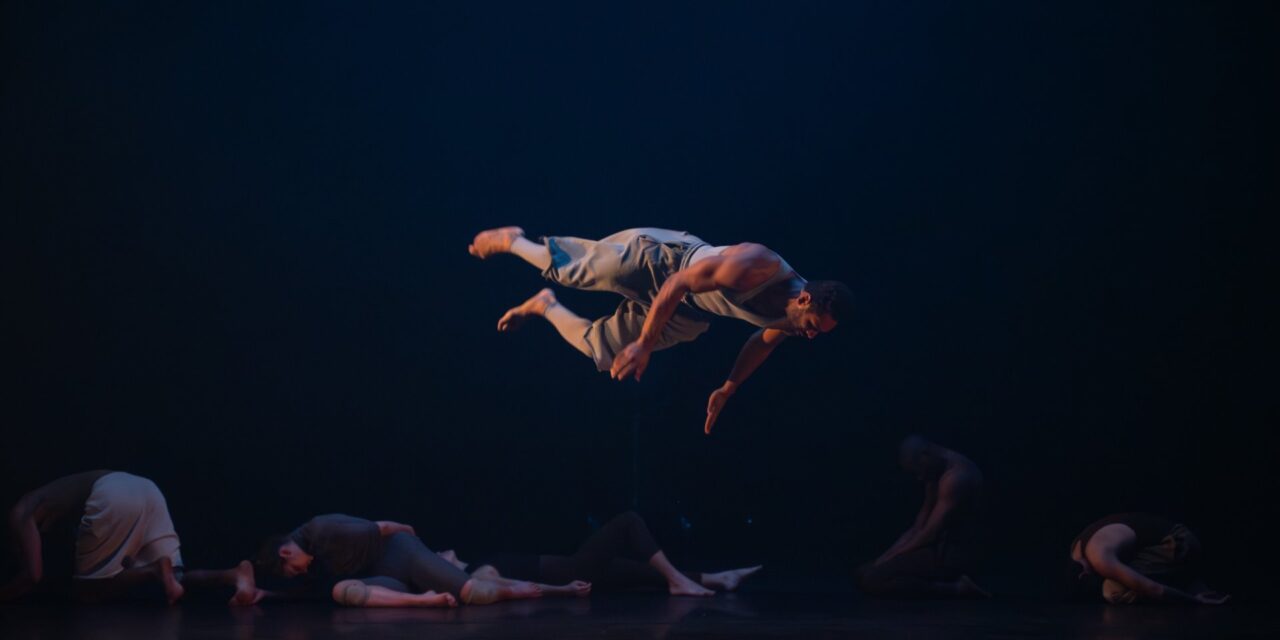

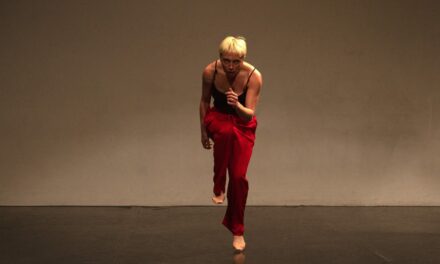

Jacob Jonas The Company in COYOTE FOX WOLF DRAGONFLY BUTTERFLY BEE EAGLE RAVEN HAWK, choreography by Jacob Jonas – Photo by Josh Rose.

As the audience gathered at the soundstage entrance, smoke billowed theatrically, heightening anticipation. The crowd—young dancers, seasoned professionals, mentors, retirees—buzzed with excitement about entering a space shared by Jonas and Mearns. Jonas soon appeared briefly, thanking the audience with disarming humility and offering a loose outline of the evening’s events. Not having retrieved a program nor QR Code, the timeline and dancer/performers remained vague, adding to a sense of mystery.

Inside the cavernous soundstage, a near football-field-sized, slightly raised mylar platform dominated the room. In dim, diffused light, dancers in nude bodysuits rolled, rocked, slammed, and fell in a continuous physical drone. As the audience scrambled for limited seating or floor space, imitating the art before them, their bodies also collided with the ground in relentless repetition.

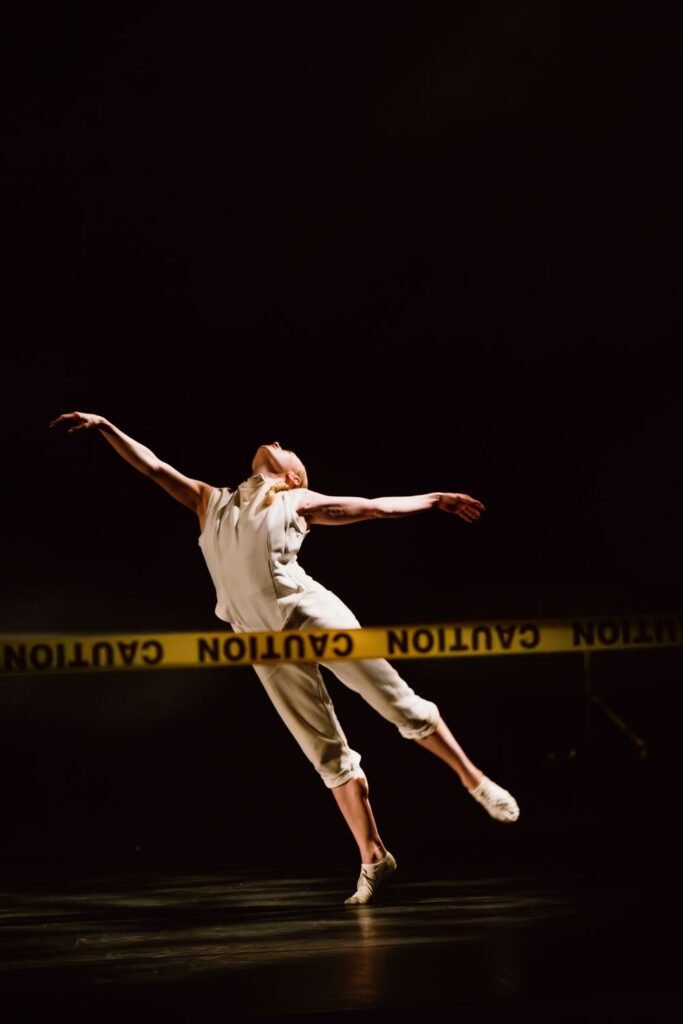

Upon settling, the introduction was abruptly interrupted by a tall, blond dancer, later realized as Sara Mearns herself, in a white, astronaut-like costume. After her quiet entrance, she began running the perimeter of the space, stringing yellow “caution” tape around the massive stage. It evoked a crime scene or wrestling ring—an unspoken warning not to cross, not to interfere, not to escape. The audience sat alert, adrenaline engaged, yet immobilized through a good half hour that seemed to neutralize her dynamic power.

What soon followed was a prolonged continuum with the Company—nearly an hour—with bodily collapse and recovery, repeated again and again. The experience recalled the Milgram obedience experiments of the 1960s, in which participants were tested on how far they would go under the authority of instruction. Here, the authority was artistic. The experiment asked: how long would the dancers endure? How long would the audience watch? And why would no one intervene?

Jacob Jonas The Company in COYOTE FOX WOLF DRAGONFLY BUTTERFLY BEE EAGLE RAVEN HAWK, choreography by Jacob Jonas – Photo by Josh Rose.

The work relied almost entirely on grueling and unrelenting physical demands as its expressive vocabulary. Falling, slamming, and exhaustion accumulated without transformation or relief. In a world already saturated with images of violence, disease, and suffering, this performance offered no context beyond endurance itself. Light occasionally suggested escape, but the choreography never followed through.

Jonas’ personal experience appeared to loom over the evening as an unspoken frame of reference. The work nonetheless suggested that this narrative took precedence over others. In its execution, there was a notable emotional distance in the treatment of the dancers—young artists whose bodies are their livelihoods—or for an audience carrying its own private burdens. Five minutes of this intensity might have communicated the point. Nearly an entire evening felt punitive.

Most concerning as a former dancer and head of an organization that bridged dancers from career to civilian life because of injury or age, the question was, long term, what will be the cost to the dancers? This level of sustained jumping and landing on knees, hips and backs risks long-term impairment and shortened careers. The body is the instrument, and yet was treated as expendable in service of spectacle. Martha Graham described dance as “the hidden language of the soul,” where the body reveals inner truths beyond words. On this night, the bodies spoke loudly.

Jacob Jonas The Company – Jill Wilson (center) in COYOTE FOX WOLF DRAGONFLY BUTTERFLY BEE EAGLE RAVEN HAWK, choreography by Jacob Jonas – Photo by Josh Rose.

And yet, the evening concluded with a standing ovation.

Why? Why was the reaction of mentors, benefactors, peers, and leaders silent? Why does the dance world so often equate physical extremes with significance, intensity with insight? Why do branding and personal mythology quell critical thinking?

This was not a meditation on the human condition so much as a prolonged demand for attention: feel what I feel; know my pain. Redemption, healing, and release — so essential to Jonas’ own survival story— were conspicuously absent. What remained was upheaval without transcendence.

The concern is not that Jacob Jonas lacks talent—he clearly possesses it. The concern is whether this fixation becomes a cul-de-sac rather than a passage forward. Impact alone is not meaning. Intensity without transformation is not depth. And applause does not confer truth.

In this case, the emperor—celebrated, applauded, unquestioned—stands exposed.

For more information about Jacob Jonas The Company, please visit their website.

This review was edited on Saturday, December 26, 2025.

Written by Joanne DiVito for LA Dance Chronicle.

Featured image: Jacob Jonas The Company – Nic Walton (In air) in COYOTE FOX WOLF DRAGONFLY BUTTERFLY BEE EAGLE RAVEN HAWK, choreography by Jacob Jonas – Photo by Josh Rose.

I am old enough to have seen a few generations of dancers, each with its heroes and artistic fixations. It is my observation that the dancers of today are overly impressed by extreme physicality. I see it in my own company members who “ooh” and “ahh” when they see something difficult being executed. I maintain that physicality is only one element of dance and not the whole of it. Maybe it is our troublesome world that makes these young dancers admire extreme physicality so. From an audience’s viewpoint, the physicality is the first level of understanding a dance. If dancers do difficult things, audience members can say “Wow, I couldn’t do that; they must be good.” In order to make a dance meaty and multi-layered, it needs to go beyond the physical tricks and into another realm. That is the difference between sport and art, I think, at least in small part.

I did not go to this performance, mostly because the marketing seemed to show people slamming themselves on the floor. Not interesting to me. Enduring cancer is so incredibly painful and soul wrecking; I can imagine this choreographer wanting to share his pain. I have a number of friends suffering from cancer, and it is not pretty. It must be hard to go beyond the pain when making a dance; choreography is hard enough already without the burden of sharing a frightful and life changing experience, but it has been done and can be done.