On July 22 Artistic Director Heidi Duckler gathered a small crowd of curious spectators on the rooftop of the Bendix Building high above downtown Los Angeles for a four-part program that showcased her latest choreography with the A Bela e a Fera Salon. Inspired by Jewish-Brazilian writer Clarice Lispector’s short stories, each section was characterized by a strong feminist voice that reverberated through Ovation-winner Paula Rebelo’s gentle narration of the writer’s work. The soundscape created powerful imagery which reflected in the dancers’ movements and engulfed the audience in an intimate world of shared introspection.

Established in 1985, Heidi Duckler Dance is one of the longest running companies in Los Angeles. Their forte is site-specific work and the selected location for this performance was the Fashion District—once known as a feminine threshold in Los Angeles when it was called the Garment District in the 1920s. At the center is the old Bendix Aviation Corporation developed by Florence Caster in 1928. Today it is considered a city landmark with its vertical neon sign burning brightly against the night sky every evening since it was relit in 2003. The building’s history and the portraits of the former Garment District’s working women hanging all along the walls of the 11th floor made it an appropriate setting for Duckler’s production.

Such Gentleness kicked off the show in the hallway with company performer Lenin Fernandez leaning out of a tall, open window in a teal jumpsuit and pigtail braids. Rebelo’s pre-recorded narration carried Fernandez through a wistful dance full of sweeping movements, swinging limbs and subtle melancholic expressions that barely registered beyond stoic. Lispector’s work discussed the discovery of gentle joy within oneself and the initial guilt that comes with accepting it. The passage set the tone for the entire evening. Not long after Rebelo’s voice, accompanied by Joe Berry’s soft piano-based composition, played out from the speakers, Fernandez stepped onto an illuminated, plexiglass table. Quick, erratic shifts led to structured poses—the dancer stiffly spread his limbs and looked at his hands and feet upon the white table top as if searching for answers.

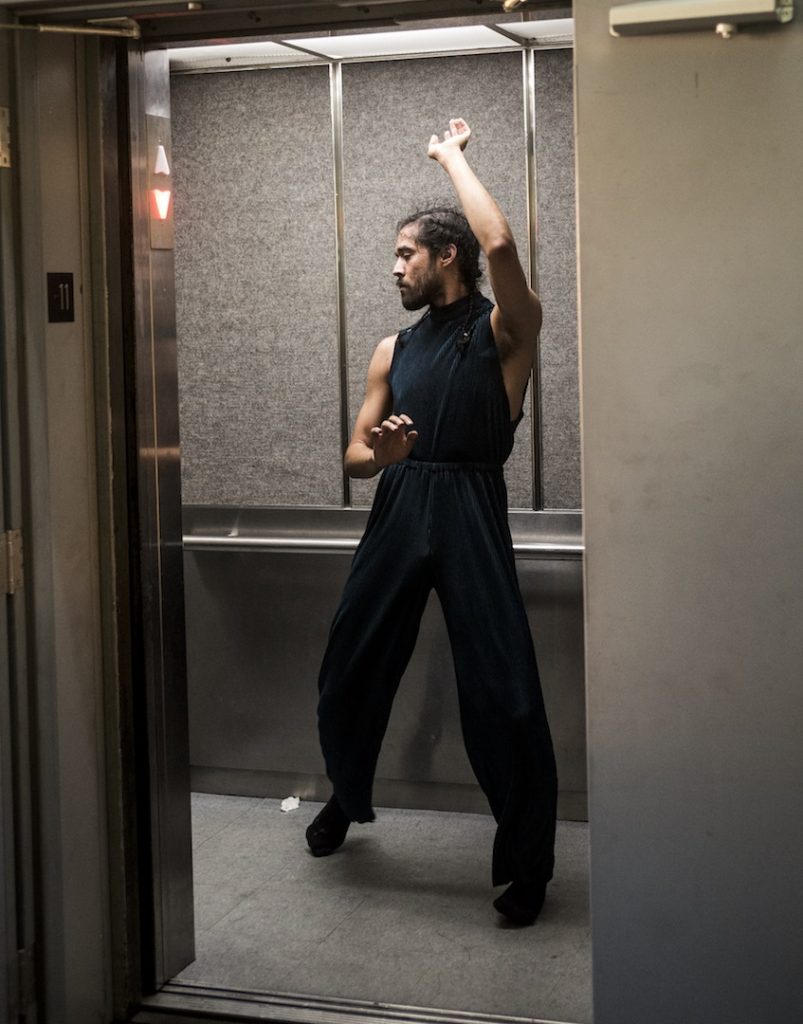

Once back on the floor, Fernandez weaved through audience members, sometimes lying flat up against a wall, other times crouching back into an armchair with a defeated look before vibrating his body away from the cushions and their comfort. At certain points he would turn away from the viewers, hide his face and hug a long column centered in the middle of the hallway, his arms outstretched behind him as the congregation shifted around the room to get a better look. The piece ended with Fernandez calling an elevator, dancing in the doorway before its arrival. Once inside, he reopened the doors by extending his arm past the threshold and back out into the hall with a firm straight palm as if hesitating to ride it down. Moments later, he finally allowed himself to leave.

A short pause and reconvention into the connected office marked the beginning of the second piece, A Bela e a Fera, which translates from Portuguese into “Beauty and the Beast.” The longest out of the four performances, this full-length work told the story of a rich woman’s encounter with a beggar on the streets of Brazil. The woman’s entire thought process, vividly illustrated by Haylee Nichele’s dancing, saw her working through thoughts of triumph, crippling doubt and self-righteousness. A small portion of the choreography took place indoors with the well-dressed Nichele establishing her character’s insecurities through short, staccato movements to Rebelo’s intro, this time paired with a soft, jazzy saxophone.

As Rebelo narrated the stress the “bela” felt when deciding whether to give the old beggar any money, Nichele pressed her body against the glass covering the floor-to-ceiling windows before suddenly slipping out of an open window onto the rooftop. Audience members trickled past her toward the few rows of folding chairs arranged to face the elevated 11th floor office which became the backdrop to Nichele’s movements.

At first, her twisting arms and legs were reminiscent of Fernandez’s dance, her short pirouettes and jutting limbs creating a few instances of choreography deja vu. The routine took an intriguing turn however with the incorporation of Carlo Maghirang’s hanging structure situated in the right-hand corner of the dance space. The machine was composed of colorful, revolving branches emerging from a single rod. Each branch was fixed with spinning handles. The prop was reminiscent of a playground toy, which Nichele would climb, push and rotate. As the “bela” grappled with new concepts that took her away from her simple world of already acquired–wealth and expanded her mind to examine philosophies such as Communism, Nichele reacted accordingly. She artfully dodged the moving branches in moments of protest, adjusted all of the handles to face the same direction when reaching a new resolution and dove underneath the entire contraption when feeling overwhelmed by all of her larger-than-life questions. Though these moments became repetitive and began to drag halfway through the dance, their redundancy and Nichele’s incessant movement began to mirror the continuous ramblings of the character’s mind, only to be interrupted by the abrupt, but pleasant lighting of the red “Bendix” sign at twilight.

A group of other untouched props suddenly drew Nichele’s attention and she broke away from the swing to don an awkward red velvet jacket that gave her a hunchback. Attached was a dragging train, under which were strangely shaped soft plush toys that unfurled into long chains. She scooped up and tossed them several times, imitating a person whose entrails and inner feelings were exposed during the performance’s climax. Eventually however, she took off the jacket and returned to a calm state of mind as she retreated back into the building.

The length of the second performance was balanced by the third portion—an eight-minute film featuring Duckler’s world premiere of The Sound of Footsteps, which played on a projector inside the office. The movie was both the saddest work of the evening and the most emotionally developed. Duckler herself performed a solo in a textile factory within the Fashion District. The piece revolved around an older woman dealing with the persistence of sexual feelings while transitioning into old age, and the disappointment that comes with feeling unwanted. As Rebelo’s voice described the character’s foray into masturbation, Duckler tumbled listlessly over large piles of rolled up cloth with a despairing look on her face. The movie went on to show her suing a red dress full of tulle (made in collaboration with fabric artist Mimi Haddon). Once it was completed, she put it on and began to twirl until completely enveloping herself in what looked like a cloud of blood and passion. She concluded by pulling the factory’s gate closed while still inside, shamefully locking herself within the confines of her own desire.

The night concluded with a short, glimpse at an upcoming piece that will premiere at the Wallis Annenberg Center of the Performing Arts in 2020. Chandelier continues Duckler’s deep dive into Lispector’s writing, but the work-in-progress seen at the salon involved more reading than choreography. Rebelo appeared in person this time to recite an excerpt from the short story of the same name. She sat on top of the plexiglass in the hallway. A sign which read “What kind of she is she?” stood propped up against a gold sequined chair while yellow tulle draped down and around the props and by Rebelo’s crossed legs. Her words described a character sleeping and feeling pleasure while lying next to her partner, indulging in the sounds of silence before being interrupted by his snoring. Rebelo’s only movement was to close her eyes and lie back on the table when she was through.

It was a welcome contrast from the tragedy presented in The Sound of Footsteps, but definitively left the audience yearning for more. Duckler conveniently set the piece up so that it would cut off before the action began. The ending was followed by refreshments and a lovely dinner all of the guests were welcome to enjoy on the rooftop.

A casual, salon setting was a good choice for an evening of dance so heavily based on abstract speculation and upsetting states of mind. One could easily get lost when putting themselves in the struggling women’s place thanks to Duckler’s deeply elaborate interpretation of Lispector’s train-of-thought style of writing. However, her choreography revealed the beauty within the beast.

For those eager to experience the salon, there will be another show on Sunday, July 29 with Raymond Ejiofor taking on Fernandez’s role in Such Gentleness and Tess Hewlett replacing Nichele in A Bela e a Fera.

For information on the Heidi Duckler Dance Theatre, click here.

Featured image: Heidi Duckler Dance Theatre – dancer: Haylee Nichele – Photo: Mark V. Lord