The first time I visited the Electric Lodge was in March 2020 for their seventeenth annual Flower of the Season, a joint bill of works by Oguri and Andres Corchero. I left that evening aware that something inexplicably special was happening in that little black box, only to wait a year and a half to return.

This year’s Flower of the Season program somehow felt like a call home, a profound meeting of newness and reflection. Together, Michelle Shiu-Lin Lai’s Tidals, Carmina Escobar’s UNFURLING IRIS, Chénhuì Máo’s When “I” becomes “It,” and an excerpt of Jay Carlon’s WAKE guided the audience through a collection of intimate human experiences in a long but lovely Sunday afternoon. Oguri and Roxanne Steinberg, co-artistic directors of the Electric Lodge, seem to be the guardians of this venue’s little community. There is a wonderfully sensitive humility in their willingness to support the artists, even if it means sweeping the stage themselves between acts.

Michelle Shiu-Lin Lai opened the evening with a text rumination on ancient rain, layering her own poetic phrases over one another with a thoughtful understanding of her loop pedal. Zenji Oguri accompanied on modular synthesizer, and once her soundscape was set, Loryn Napala joined on live kora.

Lai, bathed in whispers of the ancient rain, moved as though the detail flowed through her, almost oscillating in the corner light. She shared both resistance and shelter in a red cloth she pulled across the stage, the image of a single eye submerged in ocean waves projected on her back. Her work was just the right length, conveying a sort of patient yearning, as she researched the feeling with steady footing and faith.

Lighting design by Carol McDowell stood out first in Lai’s work and proved consistently fascinating throughout the night. McDowell’s use of shadows to create new cast members, build tension and create images all lent themselves to that sort of magic that happens in the Electric Lodge theater, intimate and nostalgic at once.

Carmina Escobar coaxed rich and warm tones from her lungs with her hand in UNFURLING IRIS as McDowell built a soft square light behind her, evoking a sort of evening window scene. Escobar, in ritual, called herself to presence in a circular pattern. She commanded her instrument with impressive clarity, especially with her mask still on, clear and communicative even to someone who doesn’t interact with extreme/experimental vocalization often. She was playful and curious, her ritual reminiscent of warm childhood afternoons spent outside, speaking and squealing delightfully without fear or filter.

Chénhuì Máo teased a durational piece, transferring rice between two buckets by the handful and asking from her ladder, “are you bored yet?” She eventually made her way to a reentrance, interrupting her own mundanity, a tablet mounted behind her head with a single eye peering out of the screen.

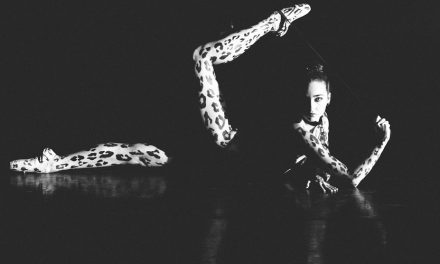

Mao’s movement was so uniquely phrased, dramatic and expressive even without the use of her face. As she jumped lithely, backwards through her hands or onto her digital scenery, she balanced a shifting timeline with bursting energy and an expert use of pause. She responded cleverly to an audience member’s cell phone ring, as though she had planned it all along, and eventually carried a television with inquisitive twin Maos offstage.

Jay Carlon worked to set up a few corners of his altar before offering condolences to the audience directly, asking their help in constructing a circle of flowers. Even Simone Forti, 86, rose from her wheelchair in the audience to offer her blooms.

There was a sense of relief in the way he introduced grief so plainly, so frankly, as his collaborator. After an evening of dense artistic theses, Carlon simply bared himself to the audience. He boxed and suffered within the altar, waging an internal war on himself with thrashing and impressively athletic movements that seemed to recall old habits and echoing blame. He was agile and responsive; he was desperate and deliberate. He dug into that punch-drunk humor only grief can teach, referencing burlesque performativity to a live recording of Eartha Kitt singing Waray Waray (a Filipino folk song).

And then he pointed with his lips and uttered the Filipino sutsot mannerism, a sound I haven’t heard since my grandmother passed five years ago. Carlon’s expression of grief spoke directly into my soul, by way of Filipino-American amalgamation expressions that just punched me in the gut. It felt like smelling the scents of your childhood home, this automatic sense-release of both nostalgia and loss. But the work didn’t only speak to one culture; its vulnerable beauty lay in full scope of Carlon’s emotions on display. He practiced each feeling with such deep commitment that the terms of loss almost changed—what better way to face the grief than to work with it? And as Mao poured her bucket of rice over him in the final shower, it seemed he may be coming into the first glimpses of acceptance.

To learn more about the Electric Lodge, please visit their website.

To learn more about Oguri, Roxanne Steinberg and Body Weather Laboratory, please visit their website.

Written by Celine Kiner for LA Dance Chronicle.

Featured image: Top L: Chénhuì Máo; R: Jay Carlon. Bottom L: Michelle Shiu-lin Lai by BWL. R: Carmina Escobar by times.brightspotcdn – Courtesy of Body Weather Labrator