Performance art is described as an art form that combines visual art with dramatic performance. There were definitely some of those ingredients at Highways Performance Space and Gallery this past weekend. Several artists joined forces to present their work under the heading of DECODE EXPLODE. One work involved speaking, an array of different sized lamps and two lamp shades. Another included a dining room sized table, three chairs and lots of drama. A third had live music and projections that literally obliterated our view of the performer. The work that commanded my full attention, however, had none of the multi-media elements or props, and the movement was powerful in its simplicity.

J. Alex Mathews is an arts practitioner who has a background in art-making, arts administration, teaching, and she is a health facilitator for More Than Sex-Ed. Mathews choreographed and performed in striking/sight, a piece that came across as a lecture with movement on sexual attraction and stereotypical views of women. At first, she had my attention when she entered the space wearing a lamp shade on her head, but then lost me as she began to perform what can only be described as bump and grind, seductive style movement before speaking at great length about what and who attracts her sexually and why. When the music returned, Mathews again writhed about in a provocative manner, even pressing herself against the back wall. I understood the message of sexual exploration, but as art, striking/light did not hold together even though Mathew’s performance was very strong. The somewhat suggestive but very pedestrian costumes for striking/light were by Joni Margaux.

Choreographed by Chantal Cherry with creative contribution by Jinglin Liao, Folie à Trois was an extremely intense work that over stayed its welcome. The story, written and directed by Tamara Rosenblum with Cherry, centers around a woman’s abusive relationship with her parents, their murder and her disturbed state of mind. Jinglin Liao plays the daughter; Kelsey Manes, the mother; and Gabriel Jimenez, the father. The movement centered at the table is terse, sharp and angular as the tension between these three increases. The table and chairs become part of the movement and sound as the trio bangs on the table, drags it about, overturns it and slams chairs onto the floor, but the choreography weakens, and the work begins to lose its strength. At one point, I began to worry more about the strength of the table than I did the performance, as the parents fought while on top of it.

The parents’ love/hate relationship ends in the husband’s murder and the daughter/mother duet hints at incest, abuse and neglect. What weakens Folie à Trois (Three Madness) was the length of the final solo by Liao. Liao’s acting, and movement is strong, but when she finally ended sitting in a catatonic state, it was difficult not to feel relief instead of concern. All three performers did a great job and I particularly enjoyed the original score by Christopher Cole.

Sadie Yarrington, Lindsey Moore Ford, Grace Phelan, Haylee Nichele in “Protest Dance/Women’s March” – Photo: LA Dance Chronicle

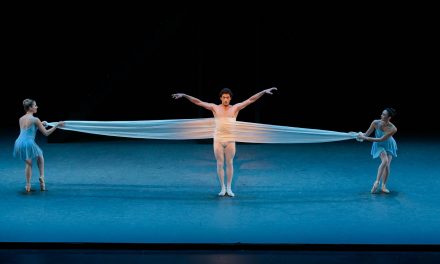

Grace Phelan has created a powerful work out of a very few and extremely recognizable gestures. Titled Protest Dance/Women’s March, Phelan, Lindsey Moore Ford, Haylee Nichele and Sadie Yarrington introduce these gestures one by one in solos that eventually unite into a protest march. They quietly confront, march, separate and reunite in a variety of ways. Phelan makes her statement on women’s rights, individual stories and continual struggle toward victory via beautifully constructed and reconfiguration of repetitive movements.

The four performers were all very different in size, shape and color, giving Protest Dance/Women’s March its sense of realness. Each performer gave an excellent performance and maintained their character throughout the piece. Phelan’s musical choices of popular songs rang true for the statement she was conveying of struggle, perseverance and solidarity. The costumes were by Kate Wright.

Collaborators Hijikata Tatsumi and Ohno Kazuo began the Japanese art form Butoh in 1959 during the post-World War II era. As is often true, they did so in reaction against the current dance scene which Hijikata felt was straining to copy the Western dance genres of ballet and modern. Therefore, he created a new aesthetic that embraced the “squat, earthbound physique… and the natural movements of the common folk”.

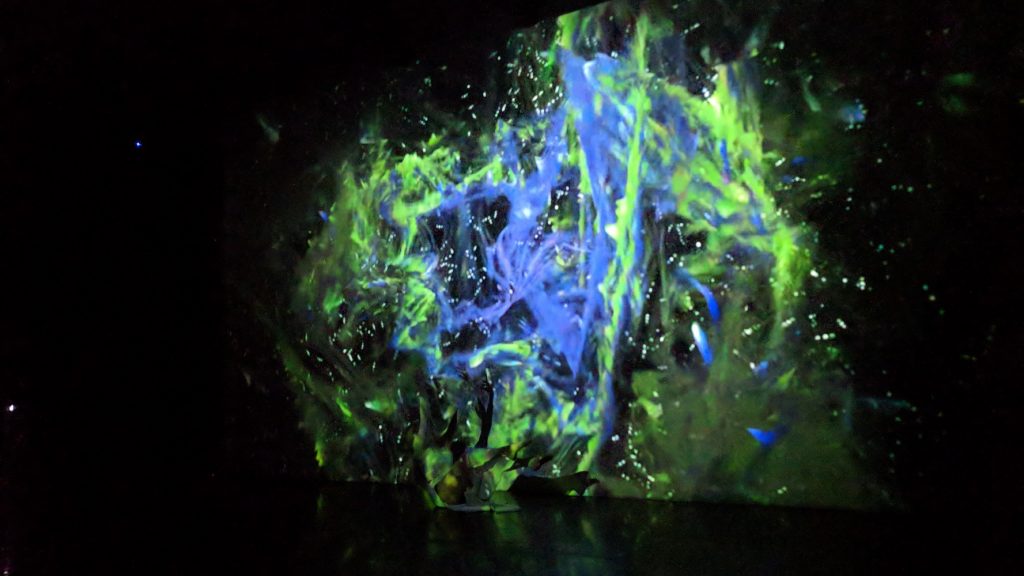

In a work entitled Maya, Caroline Haydon, in collaboration with Michael Quinn and Damie Blaise, had many of the elements of both Butoh and performance art, but the work sadly fell short of being anything more than a vehicle for Blaise’s artwork and Michael Quinn’s atmospheric music. Due to the stark and busy projections, plus the lack of any lighting on the floor, there were times when one had to search out where Haydon was performing her slow and angst filled movement. A reference that might help the reader imagine what this search was like would be to look up Martin Handford’s drawings of Where’s Waldo?

The press release states, in part, that Maya attempts to unravel the habits & pattern we develop through our experience of reality. It is my opinion that the attempt was a failure.

Featured Photo: (L to R) Gabriel Jimenez, Jinglin Liao, Kelsey Manes in “Folie à Trois” – Photo: LA Dance Chronicle