Walter Terry, the late dance critic for the New York Herald Tribune and the Saturday Review, described Bella Lewitzky as “…one of the greatest American dancers of our age.” Los Angeles was her home and the city where Lewitzky founded and ran her company, the Bella Lewitzky Dance Company. Producer, director and educator, Bridget Murnane has begun work on a new documentary titled Bella, Citizen Artist, about her former teacher and mentor, and she has launched a fundraising campaign through SEED&SPARK to help finance the completion of the film. (You can find that link at the end of this article along with a trailer for the film.) She has interviewed several people for this documentary, including dance critic Lewis Segal, and several former members of the Lewitzky dance company, and has plans to interview the remaining dance company members.

Lester Horton lived and worked in Los Angeles and his technique was inspired by Native American dance. His company, the Lester Horton Dance Group (later renamed Lester Horton Dance Theater) was also the first American interracial dance company. Bella Lewitzky was his muse and he developed the Horton Technique on Lewitzky’s body, a body with incredible strength, balance, talent and intelligence. Among the dancers who studied and performed with Lester Horton during those years included Alvin Ailey, William Bowne, Janet Collins, Carmen de Lavallade, Newell T. Reynolds, Joyce Trisler and James Truitte. Working with Horton was how Lewitzky her husband Newell T. Reynolds met. From those 1930s and 1940s roots here in Los Angeles, the Horton technique is now taught around the world.

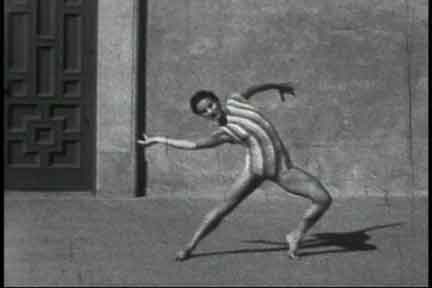

Bella Lewitzky demonstrating Horton Technique – Still from 1938 Mills College film, Dorothy Gillander

Bella, Citizen Artist documents Lewitzky’s life from the time she worked under the Federal Theatre Project (FTP), going back to her birth and upbringing at the Utopian Community Llano Del Rio and on her father’s chicken ranch in Highland. The family moved to Los Angeles in 1934 to help her father seek work. The FTP was a program that allowed many artists to work during the era known as the “New Deal”. Lewitzky performed in works choreographed by Horton and others; served as an assistant to Hanya Holm and Agnes DeMille and assisted Horton on film projects. Like many dancers in Los Angeles, Lewitzky also worked in the film industry performing as a background dancer, featured dancer and dance assistant. One such film was titled White Savage (1943) in which she performed on a large drum as a “native.”

Lewitzky left the Horton Dance Group in 1950 to develop her own work and the beautiful Carmen de Lavallade became Horton’s lead dancer. Lewitzky opened a small studio called Dance Associates and one day was handed a subpoena demanding that she testify before the House Un-American Activities Committee. Following her appearance, where she pleaded the Fifth Amendment, Lewitzky spoke the now famous words to reporters who asked her if she supplied the committee with names, “I’m a dancer, not a singer!” Later in life Lewitzky is quoted as saying. “Freedom is not a given, you must fight for it.”

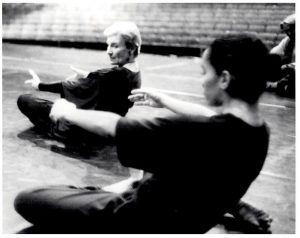

Bella Lewitzky with her husband Newell T. Reynolds – Bella Lewitzky Archives, Special Collections, Doheny Library, USC

Bridget Murnane wrote that following this appearance, Lewitzky could not “safely” work in films; colleagues would cross the street to avoid her; she received threatening phone calls; her friends had rocks thrown through their windows. The only person who would hire her at this time was Agnes DeMille, who brought Lewitzky on as her assistant on the movie “Oklahoma,” with the stipulation that Lewitzky would not receive credit.

Lewitzky founded the Bella Lewitzky Dance Company in 1966 and became the founding Dean of the School of Dance at the California Institute of the Arts (CalArts), where “she developed a multicultural/inter-arts approach to teaching modern dance.” She worked with the Los Angeles Olympic Arts Festival Committee to bring international dance companies as well as Hispanic, Asian and African American dance groups to the 1984 Summer Olympics Arts Festival.

Lewitzky’s company began touring nationally and internationally, and despite this, her work was not given that same respect from the east coast dance community. One person who loved Bella Lewitzky and her work was Merce Cunningham. One summer at the American Dance Festival in Durham, NC, I asked him who his favorite dancer was, thinking that he would name someone from his own company. “Bella Lewitzky!” He said without a moment’s hesitation.

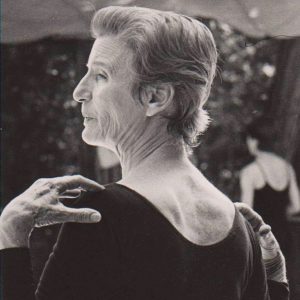

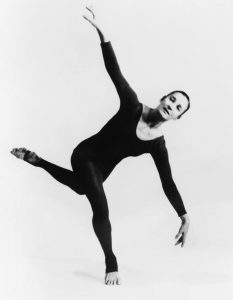

Bella Lewitzky – Photograph from the Dance Division, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts, Astor, Lenox, and Tilden Foundations.

During the early 1990s, censorship began to raise its ugly head in this country once again, and Lewitzky refused to sign an anti-obscenity clause on an acceptance form of a National Endowment for the Arts (NEA) grant. The amount was not small, $72,000; funding that her company definitely needed. She did not stop there although her company was temporarily disband due to lack of funds. Lewitzky joined with People for the American Way to sue the NEA director John Frohnmayer. She won the case and was finally awarded the grant money. It was a landmark case and because of it “Individual grants are no longer given to artists but must be supported by institutions”.

The Bella Lewitzky Dance Company gave its final performance at the Luckman Theatre at California State University, Los Angeles on May 17, 1997. When saying goodbye to her company and to her audience, Lewitzky said. “The arts are under threat more than ever before. What legacy I have left here will die unless you become responsible for keeping it alive.”

The Dance Heritage Coalition designated Lewitzky one of America’s Irreplaceable Dance Treasures and she was awarded the National Medal of Arts by President Clinton. Bella Lewitzky died on July 16, 2004 at the age of 88. Murnane wrote, “Lewitzky’s life demonstrates how a “uniquely Californian” artist with vision and tenacity can change the lives and landscapes of her fellow citizens for the better.”

Lewitzky’s work Kinaesonata (1970), choreographed to Piano Sonata No. 1 by Argentinian composer Alberto Ginastera, will be reconstructed for Los Angeles Dance Project (LADP), and is scheduled to premiere in 2019. In their promotion of this revival, LADP states, “The work of dancer, choreographer, educator, caring humanitarian and champion of freedom of expression, Bella Lewitzky, returns to Los Angeles.” They also site a wonderful quote by Lewitzky: “To exist merely to exist is stupidity. To exist to make art is a pretty grand act.”

A campaign to raise funds for Bella, Citizen Artist will commence on October 1, 2018. Its Producer and Director, Bridget Murnane has had her films screened in over thirty international festivals, on the PBS series, New Television and The Territory, as well as Classic Arts Showcase on cable TV. She has received several awards including two CINE Eagles. Her first feature, Odile and Yvette at the Edge of The World, premiered at the Edinburgh Film Festival and received special recognition from the Advisory Board and the Brussels Diamond Film Festival. She was Associate Producer and Interviewer on Mia, a Dancer’s Journey, which won an Emmy for History, Art and Culture. The Mia refers, of course, to the well-known ballerina Mia Slavenska, who also taught at UCLA for many years.

Bridget Murnane needs our community’s support so that she can finish this very important documentary on one of Los Angeles’ and America’s dance treasures. We cannot let Bella Lewitzky’s legacy disappear. Here is the list of people involved in the making of Bella, Citizen Artist:

Former Bella Lewitzky Dance Company member, rehearsal director, choreographer and teacher Walter Kennedy, and choreographer, director and dancer Jordana Toback are Associate Producers. Pat Verducci, who has written screenplays for Touchstone Pictures, Witt-Thomas Productions, and Disney’s animation division, worked as a story consultant for Disney/Pixar as part of their “Story Trust,” and who wrote and directed the feature film True Crime is Writer, W.G.A. The Cinematographer is Morgan Sandler, a professor at State Los Angeles where he helped to design the digital cinematography program. Pam Wise, Editor, A.C.E., edited the award-winning films Transamerica, Dark Matter, Secretary, and Dancemaker, the 1998 A.C.E. Eddie Award Winner for Best Edited Documentary, Dancemaker, and a member of the Motion Picture Editors Guild, American Cinema Editors, and the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Science. Celia L. Mercer is Design Director. Her award-winning animated films have screened internationally, and Returning to the UCLA School of Theater, Film and Television as the second Senate Faculty member in Animation in 1996, Professor Mercer became Area Head of the UCLA Animation Workshop in 2007. The Trailer Editor and Assistant Editor is Alex Bushe, a Los Angeles-based editor with experience in both fiction and nonfiction filmmaking. He has worked on over 20 films, including 6 features with renowned director Werner Herzog.

The Fiscal Sponsor for Bella, Citizen Artist is The International Documentary Association which is “dedicated to building and serving the needs of a thriving documentary culture. Through its programs, the IDA provides resources, creates community, and defends rights and freedoms for documentary artists, activists, and journalists.”

For more information on Bella, Citizen Artist, click here.

To make a tax-deductible donation, click here.

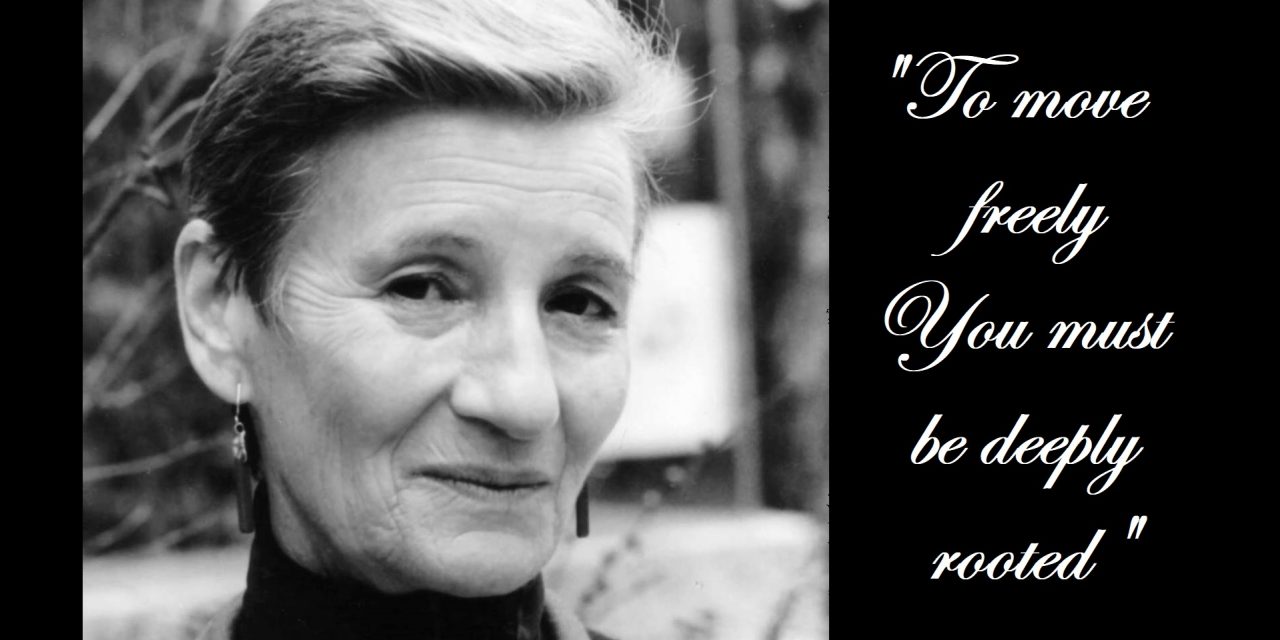

Featured image: Bella Lewitzky and one of her quotes. Photo from the web.