For sixty years, Twyla Tharp has audaciously carved new places for her singular style that expanded existing definitions and expectations in contemporary dance, ballet, film, and Broadway. Celebrating that six decade milestone, Tharp and her dancers arrive in SoCal for performances at Costa Mesa’s Segerstrom Center for the Arts (Feb. 15-16) and Cal State Northridge’s The Soraya (Feb. 22-23). No surprise, Tharp eschewed any ‘greatest hits’ program, instead selecting her Olivier-nominated Diabelli Variations that tackles the Beethoven piano masterpiece and bringing a new dance set to Philip Glass’ Aguas da Amazonia, arranged and performed by Third Coast Percussion.

While today her name is recognized beyond the dance world, even dancers do not always fully appreciate Tharp’s impact, how she was in the forefront of breaking down barriers, expanding the definition of dance, and launching extraordinary, sometimes previously overlooked, dancers.

Joffrey Ballet and Deuce Coupe

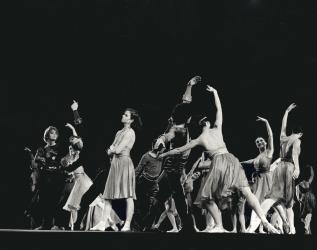

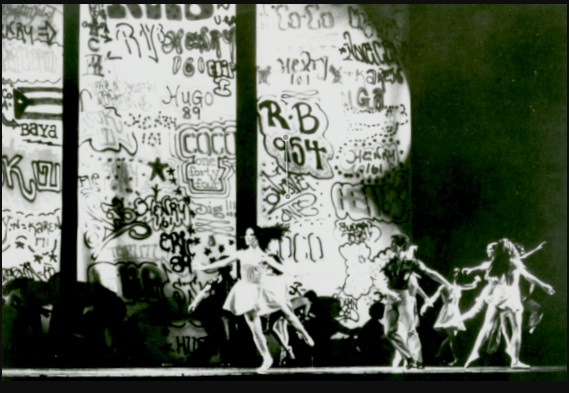

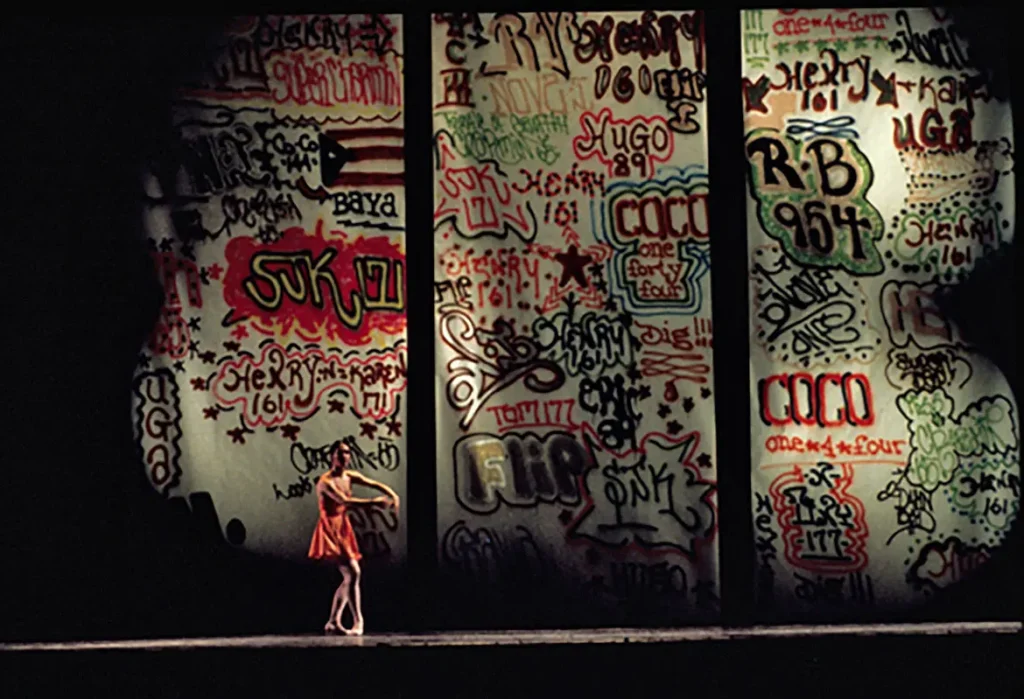

Twyla Tharp was already a rising presence in New York’s modern dance world in 1973 when the music of California’s Beach Boys catapulted her onto the national stage. For roughly eight years, Tharp had built a company and reputation while refining a distinctive, dance style that was serious dance, but also provocative, frequently off balance, and often fun. The turning point in 1973 came from Robert Joffrey who commissioned Tharp to create a new work for his Joffrey Ballet. The result was Deuce Coupe. Tharp set Joffrey ballet dancers and Tharp’s contemporary dancers on the same stage in their respective vernaculars, backed by popular California surf music while graffiti artists created a backdrop in real time.

Raised in Southern California in the 1950s and early 60’s during the Beach Boys’ heyday, Tharp’s choice of their music and the successful audacity of the Tharp/Joffrey collaboration, drew younger audiences that came knowing the music, but caring little for ballet or modern dance. Yet many left curious about more than just the music.

Joffrey Ballet in Twyla Tharp’s ‘Deuce Coupe’ (1973) with United Graffiti Artists painting backdrop – Photo by Herbert Migdoll.

With its critical and popular success, Deuce Coupe became a milestone “crossover ballet,” defying acknowledged barriers between ballet and modern dance. Today, the terrain between ballet and contemporary dance has largely open borders, but with its combination of two different companies, the use of popular music, the graffiti artists, and Tharp’s distinctive movement, Deuce Coupe was a significant turning point. Over the years since, ballet companies found both artistic and bottom line reasons for “juke box” ballets to Elvis Presley, the Beatles, Prince, Johnny Cash, Etta James and others. Fans of the music saw ballet dancers in tennis shoes and cowboy boots, as well as pointe shoes. Some of those new audiences drawn by the music returned for feathered swans and sleeping princesses, as well as dance with less familiar contemporary music.

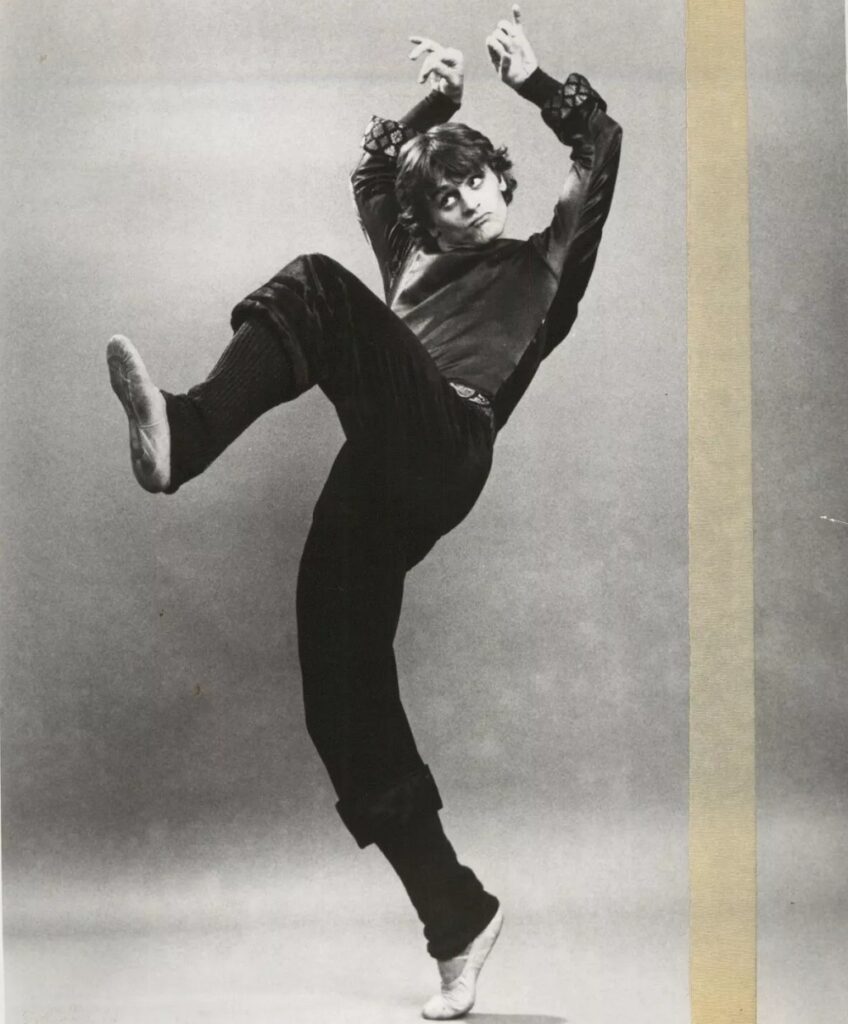

Twyla Tharp in “Deuce Coupe” (1973), a ballet commission by the Joffrey Ballet – Photo by Herbert Migdoll/The Joffrey Ballet.

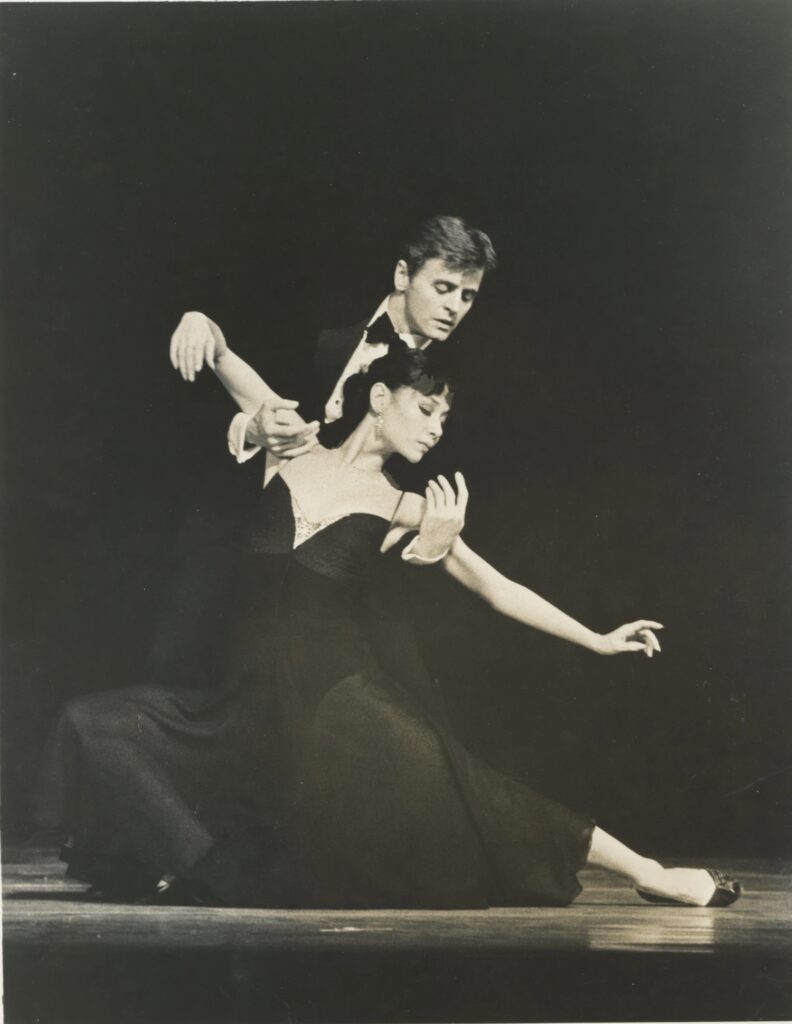

American Ballet Theatre and Mikhail Baryshnikov

Despite the attention Deuce Coupe drew, the Joffrey Ballet was considered an upstart, primarily focused on contemporary ballet. Three years later, Tharp entered a bastion of classical ballet, American Ballet Theater. Reigning superstar Mikhail Baryshnikov wanted to move beyond the princes of classical ballet. He saw Deuce Coupe and worked on mastering Tharp’ off-kilter, non-balletic style. His interest led ABT to invite Tharp to create a new work centered around Baryshnikov.

Mikhail Baryshnikov in “Push Comes To Shove”, choreography by Twyla Tharp – Photo courtesy of the artist.

ABT’s reputation was built on full-length classical ballets, but the repertoire had a roster of non-classical ballets including Eugene Loring’s western Billy the Kid, Agnes DeMille’s cowboy-themed Rodeo, Anthony Tudor’s conflicted wedding party in Jardin Aux Lilas, and Jerome Robbins’ Broadway-flavored Fancy Free. The contemporary movement and music did not stray far from the classical. DeMille’s booted central tomboy and Robbins’ sailors cut some non-balletic moves, but overall the ballets were firmly rooted in classical ballet. Tudor brought modern dance moves that sometimes required rigidly trained torsos to contract in un-balletic ways but translated those modern dance elements onto classical moves and classical music. Then came Tharp’s Push Comes to Shove in 1976.

In 2008, Elaine Kudo recounted to Playbill Magazine the impact she witnessed as a first year ABT company member as Tharp set Push Comes to Shove. “Many in American Ballet Theatre were so skeptical that they asked not to be in it, and to stay in their comfort zone. Steps that were being used in tandem were so odd for the time, so very different from any motions used in classical ballet, that dancers were saying, ‘She wants me to do what?!’ For instance, to rotate one way, change your weight and go the other way is not a ballet dancer’s tendency.”

Tharp did invoke some classical music, interlacing Joseph Haydn’s rather rollicking Symphony No. 82 in C, The Bear, with the distinctly non-classic Bohemia Rag by Joseph Lamb, because she wanted to show the similarities in the use of syncopation. The three leads, Baryshnikov, Martine van Hamel, and Marianna Tcherkassky, led a large group of dancers with no explicit storyline, just a focus on the exchange of a black derby hat as they executed Tharp’s off-kilter, off balance moves.

Initial reviewer reaction included headlines like the New York Times’ “Twyla Tharp’s Descent Into Slapstick” and “Baryshnikov Becomes a Tharpist.” Respected reviewer Wendy Perron declared Push Comes to Shove was “when Baryshnikov became an American.” Some reviewers sniffed and questioned if this should be considered ballet while others saw a through line from Jerome Robbins and Agnes DeMille. The hallowed halls had been breached. Late in his tenure as ABT artistic director (1980 to 1989), Baryshnikov officially brought Tharp into the company as an Artistic Associate.

Film and Broadway

After ABT, Tharp reestablished a company and also choreographed for a range of ballet and contemporary companies. Along the way, Tharp choreographed movies – Hair (1978), Ragtime (1980), Amadeus (1984), White Nights (1985), and I’ll Do Anything (1994). Broadway hosted Tharp with Billy Joel’s music (Movin’ Out), Bob Dylan (The Times They Are A-Changin’) , and Frank Sinatra (Come Fly Away). Particularly with the long-running Movin’ Out, Tharp joined Matthew Bourne in the rarefied group of choreographers able to draw audiences to dance-only theatrical events for extended runs, not just a weekend of performances. Broadway had long drawn on choreographers like Robbins, DeMille, and George Balanchine to choreograph dance for musicals, but Tharp and Bourne are rare in creating dance-only theater, not just once, but multiple times. While Bourne often reconsiders classic ballets using the classical music, Tharp’s theater ventures draw on iconic singers.

Throughout her career, Tharp’s companies have reflected her eye for talented dancers who sometimes did not fit the usual molds. “We sometimes described ourselves as a tribe of misfits,” according to Charlie Neshyba-Hodges who danced with Tharp’s company starting in 2005. Reflecting on his years with Tharp, Hodges echoed other dancers’ comments about Tharp’s discipline, commitment, brutal honesty, and her ability to see and draw out dancers’ potential.

“If dance is my natural language to understand the world and my place in it…then Twyla taught me how to speak,” he explained. “When Twyla offered me the job to dance in her touring company, I responded with concern that I was too fat or too short, since I grew up in a ballet world where company after company noted that the shape and size of my body were problematic to ballet’s expectations. She replied, ‘I’m in the business of hiring good dancers, and you are a great one.’ So that same world that saw me as problematic would also see Twyla hiring me as an act of rebellion. She often gets this moniker.”

Hodges went on to dance for Tharp on Broadway, picking up awards and award nominations for his work in Come Fly With Me (2010).

“Looking back, Tharp doesn’t coach the way many do,” Hodges recalled, “She does not micro-manage the angle of a head, or the placement of the ribs. She expects you to be on your leg, to control your center in order to throw your body off it. Her job is to make movement; my job is to execute it. What is essential to Tharp is that a dancer learn to listen to the music and be in the moment. Try as we might try to plan for every eventuality, life has a brilliant way of still surprising us. Instead of resisting this, or denying it, her work and her coaching asked me to partner with it. With Twyla, I learned that people are too quick to accept failure, instead of expect failure. There is a huge difference. Failure is an essential part of any process, but a complete outcome requires getting to the other side, time and again. Accepting failure is a stopping point. Expecting it is a threshold. There is nothing that Twyla expects of a dancer that she doesn’t endure herself,” Hodges concluded.

For her 60th

The anniversary program brings something old and something new. From 1998, Tharp’s Diabelli Variations explores the 33 variations that comprise Beethoven’s solo piano work of that name played by pianist Vladimir Rumyantsev.

In 1999, reviewer Judith Mackrell of Britain’s Guardian newspaper wrote: “As Beethoven shakes his little theme into hundreds of different rhythmic and dynamic patterns, so does Tharp. As Beethoven parodies forms and manners, so does Tharp. She colours her own material with jazz, high camp and tender sex, creating some of the best dance of her recent career.”

Slacktide, the second work on the anniversary tour, finds Tharp drawing on a 1993 chamber work by Philip Glass, Aguas da Amazonia. The music received a new arrangement for the occasion and will be performed by Third Coast Percussion.

According to her biography, Tharps’ current oeuvre totals 160 works–129 dances, 12 television specials, six Hollywood movies, four full-length ballets, four Broadway shows and two figure skating routines. If this tour with the new work is any indication, there is more to come.

Twyla Tharp Diamond Jubilee at Segerstrom Center for the Arts, 600 Town Center Dr., Costa Mesa; Sat., Feb. 15, 7:30 pm & Sun., Feb. 16, 1 pm, $44.07 – $134.47. https://www.scfta.org/. Also at Cal State University Northridge, 18111 Nordhoff St., Northridge; Feb. 22, 8 pm, Sun., Feb. 23, 3 pm, $47-$128. https://thesoraya.org/en/

Written by Ann Haskins for LA Dance Chronicle.

Featured image: Twyla Tharp Dancers – Photo courtesy of the artists.