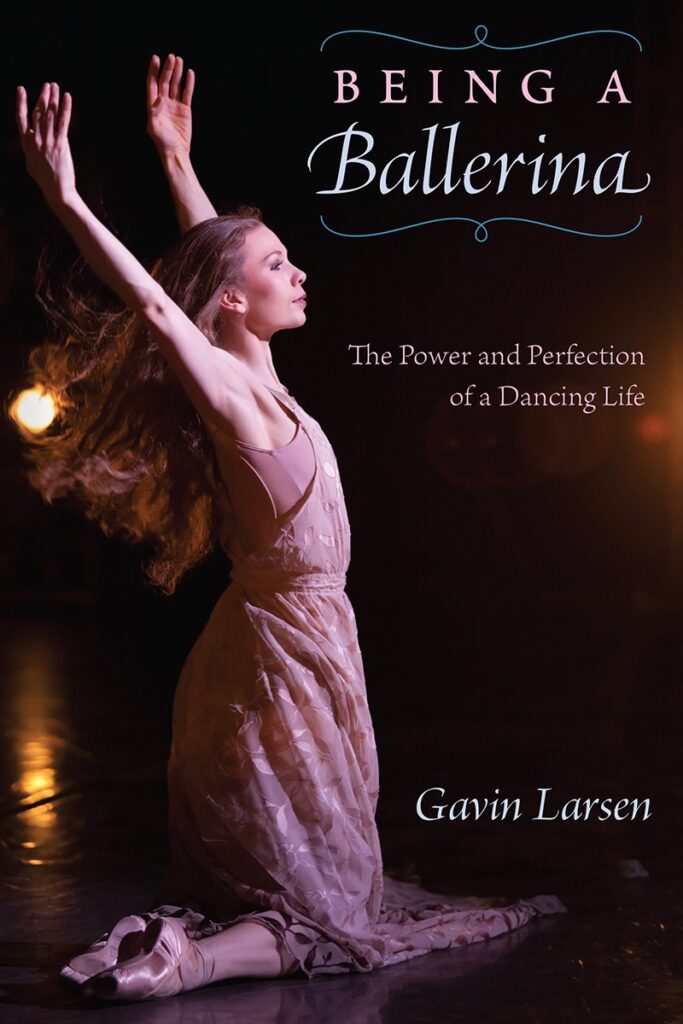

Gavin Larsen is a dancer’s dancer. She was a beloved principal ballerina, transitioned to a treasured teacher, and is now deep into a brilliant writing career. We spoke about the trials and tribulations of a normal ballet career and what that means, moving through injury and aging as a dancer, mentoring, and landing in her current work, shifting her artistry from the stage to the written word; in her memoir, Being a Ballerina, The Power and Perfection of a Dancing Life, a Substack, for dance publications such as Pointe, Dance Teacher, Dance Magazine and for literary journals. Her upcoming collaboration with photographer Gene Schiavone, Infinite Steps, Thirty-Three Dancers and Their Lives in Ballet, is now available for pre-order and will be published in March of 2026.

We had a wide-reaching conversation on the depiction of ballet in the media world, female mentorship, and transitions, from dancer to teacher, to writer, and back. Ms. Larsen is a fascinating, inspiring individual, and I recommend her lyrical, beautiful writing, whether you are a dancer or not.

I first started reading Ms. Larsen’s work in her luminous memoir, Being a Ballerina. In it, she shares her trajectory from a student at the School of American Ballet, through corps positions at Pacific Northwest Ballet and soloist positions with Alberta Ballet and Suzanne Farrell Ballet, eventually landing in Portland, where she was a principal with Oregon Ballet Theater. She retired from the stage in 2010 to focus on teaching and writing. The dance world that she writes about is real and relatable, with nary a Black Swan psychotic episode in sight.

One of my main missions in writing this book was just to dispel those myths. The way ballet is portrayed in the media drives me crazy. And even worse than that, it makes me mad because it’s really discrediting and disrespectful to my art form and my life; of who I am, of all of us; to who we are as people. You go out into the world and you tell someone you are or were a ballet dancer, and they immediately have this manufactured image of what that means, and it’s completely false. I’m still on this mission to dispel the myths in the general public about what it means to be a dancer; what that identity is, and what the life is like.

One of the aspects of ballet that is often overlooked or looked at only in relation to the biggest names, is that of mentorship, of passing the knowledge of one generation to the next. Ms. Larsen writes eloquently about the mentors that shaped her view of ballet, from her teachers at SAB, Francia Russell at PNB, to Suzanne Farrell, and then Damara Bennett at OBT. (In full disclosure, Ms. Bennett, who passed away in 2020 after a long battle with breast cancer, was one of my mentors in San Francisco)

She [Damara] was a huge influence on me, too. And there was a period of time when I was there [at OBT] that we were quite close. I felt like she was guiding me along, and I had that mentorship. I learned so much about teaching from Damara. I teach a lot of her combinations, still to this day. I feel like she’s always kind of on my shoulder.

Ms. Larsen relates a formative experience as a young dancer, when Francia Russell taught her the waltz girl in George Balanchine’s Serenade.

That’s something that’s really important to me, that sense of lineage. I always felt, when I was learning a piece of existing choreography that was new to me, that I was tapping into everyone who had danced it before. That’s actually something that Francia Russell first said to me when she was teaching me a role in Serenade. She asked, Oh, have you learned this yet? And I said, No, no, I’ve never learned this part. …. She took me by the hand. She said, “All right, here we go.” I realized what she meant. She had taught that role to so many dancers. She welcomed me into this club of generations of people who danced those very same steps. I could see how much that meant to her to be helping pass from one person to another.

I feel that same way about teaching. It’s so palpable, and it’s so important in this world where every single day, something else is automated, and a robot or an inanimate object is taking over for a human being. I couldn’t feel more strongly about the human-to-human passage of dance and the way that bond cannot be broken. It’s just something that can’t be automated. And to me, that’s incredibly precious.

The passing of the Balanchine torch sounds very heady and elitist, but what struck me the most about the memoir was how normal everything was, how real it seemed. Not everything worked out; she didn’t end up in New York City Ballet but still found her way.

Oregon Ballet Theatre – Gavin Larsen with Artur Sultanov in “Duo Concertant” – Photo by Blaine Covert.

I have a lot of thoughts about that. I think it’s uniquely American that your resume is seen as a measure of your validity. I think one reason why it doesn’t seem that way in Europe is because there are a lot of social and cultural differences. In most other countries, you don’t have to prove your right to exist and to live a wonderful life on this planet. You don’t have to earn your right to health care. You don’t need to work your way to a good place to live, food, and housing. So as an artist, as a dancer, you don’t need to be the star of the most prominent company in the country. Europeans recognize that being an artist is a valid, honorable, important thing, whether you’re famous or not. In the United States, it’s just so different. Our mindset and our cultural outlook is fixated on prestige, accolades, resumé, track records, accomplishments, and numbers. I think that’s why so many ballet dancers have this insecurity about themselves. Maybe they weren’t in the most fancy school, or they didn’t have a big scholarship, or they weren’t in the most prestigious company or a principal. But as a corps de ballet member in a company in the Midwest that doesn’t tour internationally, you are still a really important contributor to this culture and to this art form. So one of the early titles of this book, before I settled on “Being A Ballerina,” was “The Everyday Ballerina.”

She emphasizes;

Ballet is not untouchable, and ballet dancers are not untouchable. They are not crazy. Being a dancer doesn’t inherently mean that you’re messed up.

Ms. Larsen continues this line of inquiry, that of a ballet dancer as a normal human person, in her collaboration with Gene Schiavone. In her interviews with the dancers profiled in the book, she heard them speak of mentors, lineage, and other performers, about belonging and elitism, the American dance hierarchy, and how dancers themselves can shift that culture and make it caring and loving. She used American Ballet Theatre Principal Dancer Corey Stearns as an example.

Corey Stearns talked a lot about the time period when he joined ABT. The culture was not welcoming. At the time, it was, I don’t wanna say cutthroat exactly, but the hierarchy was so strict. As a newcomer, any misstep was immediately met with, I don’t know what sort of repercussions, but he even used the word bullying, not in a literal, physical sense, but he said it felt like a bullying culture. He vowed that when he entered the company, if he stuck it out and ever got to the top, he would do everything he could to change it. Over the years, he is now a principal, and it has changed a lot. He spoke about how proud he is of the culture there now, and how supportive the dancers are of each other. I mean genuinely supportive, sincerely caring for each other, and excited for each other.

The dance world that Ms. Larsen and I entered was very different from the dance world today. Dancers can attend college, conservatories, or training programs and enter companies at 20, 21, or 22, still having great careers. There are mentorship opportunities and college programs that cater to professional dancers and to their schedules. There is social media, which can bring the everyday grind of being a dancer into the consciousness of young aspiring dancers.

I ended the interview with a focus on the future. How does Ms. Larsen think that she can influence dance leaders into the next generation?

I try to subtly impart upon them that studying dance is an act of self-empowerment. The skills that you are learning and developing in the dance studio are going to enable you to go really, really far, even if it’s outside of dance eventually, But, if you stay in the dance world, the self-assurance, confidence, competency, focus, aspiration you’ve been fostering during your training combined with your ability to follow, will empower you to make you take over the [dance] world, if that’s what you want to do. That’s the message that I continue to give out. Those are leadership qualities that you’re learning and developing every single day. In the articles that I write for Pointe or Dance Magazine, I always try to add in, no matter what the topic is, the principle of the agency that you have as a dancer. The very fact that you are embarking upon a journey in this world gives you, builds in you, and brings out in you your agency and your strength. The fact is that you have this voice that you can use however you want. If you don’t want to open your mouth, then you go on stage, open your body, and if you do want to stand at the front of the room, eventually you can do it.

Follow Ms. Larsen on Substack, and when her new book comes out, be sure to find it right away.

The power of the photograph is immense in dance because it crystallizes a free-flowing art in a way that you know video doesn’t.

To learn more about Gavin Larsen and to purchase her book, please visit her website.

Written by Nancy Dobbs Owen for LA Dance Chronicle.

Featured image: Gavin Larsen – Photo by Blaine Covert.